This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

A decade into the culture wars, the argument for decolonising the museum has run out of steam. Nowhere is its critical dead end more evident than in Dan Hicks’ Every Monument Will Fall, a bewildering moralistic call for guilt and hatred of all history. “Dead”, not least because a “mediocre dead white man” haunts the museum where Hicks made his career. “Dead”, because Hicks’s attempt to escape that man’s shadow takes the form of a necrography. “Dead”, because it exorcises this ghost with no interest in the living.

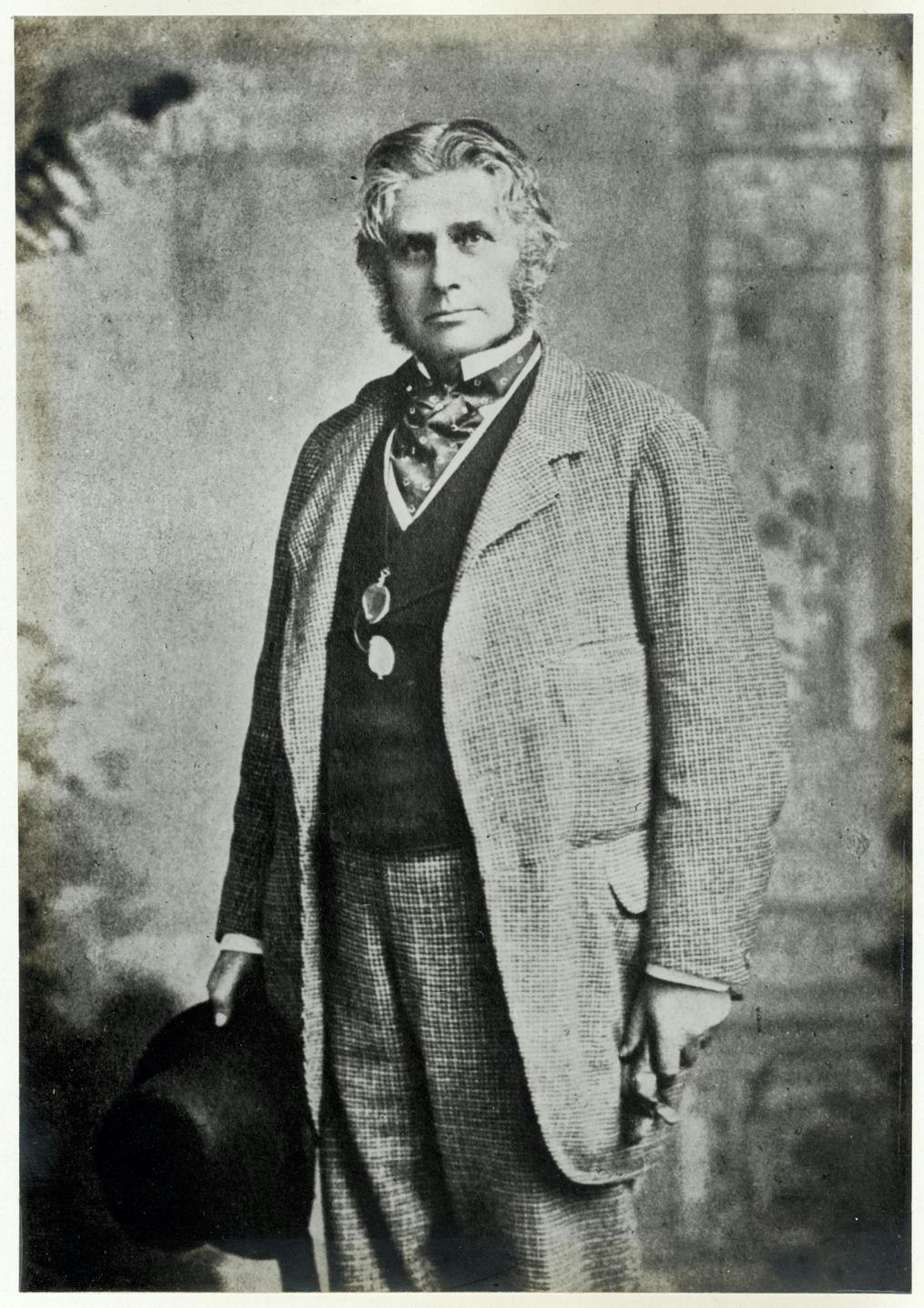

The 19th century collector Henry Lane Fox is a dark father figure to ethnography and archaeology. Fox, known as Pitt Rivers in later life, founded the collection, now the University of Oxford’s ethnographic museum, that bears his name. The museum’s website offers a scant biography, obliquely referring to Fox’s “professional interests in the development of firearms”, adding that the unusual arrangement of the collection by type and function are evidence of a “great diversity” of distinct cultures. For Hicks, this is a whitewash.

In the background of Every Monument is a sprawling portrait of Fox entrenched in the industry of killing, intellectually excusing state-orchestrated repression and unquestioningly benefitting from the spoils of slavery. Hicks’s thesis is that Fox’s understanding of world cultures was underpinned by a belief in the righteousness of Western civilisation and the cultural supremacy of whiteness. His conclusion? That the same supremacist attitudes still thrive on death today.

There are, indeed, plenty of reasons to condemn Fox, who is on record as saying his collection was organised not to celebrate difference but to distinguish developed Western from “barbaric” cultures. He did not hold back, either, in offering now suspect theories of cultural reproduction and degradation.

These ideas, Hicks suggests, became so ingrained in archaeology and ethnography that it wasn’t until 2022 that his museum removed from display Fox’s macabre collection of shrunken human heads. For him, the uproar this prompted from the conservative press is evidence of British society unreflectively venerating their inherited past. Such an attitude belongs to a death cult, one which Fox knowingly and intentionally created as a trap for successive generations.

Hicks finds evidence of that cult’s cultural transmission in material artefacts. His case study is a drinking cup fashioned out of a human skull, once in Fox’s private collection and presented to Worcester College by Fox’s grandson, George Pitt-Rivers, an undergraduate in the 1920s. Recent scientific analyses confirmed the cranium belonged to a woman who died in the 1780s. Nothing is known of her life.

Pitt-Rivers was an admirer of Hitler who attended the 1937 Nuremberg rally, published an apologia for Germany’s invasion of Czechoslovakia grounded in the inferiority of Czech culture and supported Oswald Mosley. Arrested in 1940 under wartime regulations, he pleaded for academic asylum at Worcester. This was denied because the security service thought it undesirable to expose his “objectionable views in the university”.

Hicks is not content with condemning Fox-Pitt for his overt fascism but declares it a heritable trait of the Pitt Rivers line. Indeed, he finds that fascism was and is synonymous with establishment British culture and only half-ironically proposes redefining fascism to include traits like a “love of the railways”, “the family and public education” and “an interest in inheritance and posterity”. All of these he dismisses as “irrational”. One almost hears him invoking Fox-Pitt in approval of universities no-platforming “undesirable” speakers today.

For what purports to be a serious argument for an ethical rewriting of history, Every Monument brims with anecdotes, digressions and appeals to ahistorical theory that undermine its goal. The narrative barely maintains the distinction between evidence-based fact and material drawn from hearsay and opinion. Hicks bamboozles the reader by referring to six thinkers such as Leibniz and Deleuze in the space of two pages and then switching scale to intimately address them as “you”, thus forcing nods of unwitting agreement.

Hicks might argue this is what Fox did to build the myth of a superior British culture which today’s historians must unravel. Thus his frequent hyperbole, such as his designation of the anti-decolonisation group Restore Trust as Tufton Street “Muskian astroturfers”, is thereby justifiable. But Hicks’s project loses all credibility when he imagines a juvenile Pitt-Rivers drunk from that gruesome skull cup at his grandfather’s dining table, thus becoming initiated in his bloodline’s culture of violence. Is this story true? “Who knows?” Hicks replies. “And frankly, who cares?”

It is remarkable that his project of decolonisation has had material consequences. Hicks’s 2020 book The Brutish Museums was pivotal to the restitution of the Benin bronzes, despite its central argument of British culpability in the 1897 Edo massacre being riddled with errors. Now, Every Monument opens with the rhetorical “Ever felt you’ve been lied to?”

Hicks promises he’ll cheer the decolonising mob toppling the next statue. But as forceful as Hicks is in indicting legacy culture, one will look in vain in Every Monument for a positive moral argument. The text offers no cogent theory of absolution that might result from the denunciation of one’s forefathers. He promises neither earthly nor heavenly reward for the restoration of dignity to the human remains once labelled as “barbaric”. Instead, he conjures the image of himself gazing at the skull cup as though he were Hamlet.

This tableau mort might offer psychoanalytic insight into how Hicks emancipated himself from his discipline’s colonial, fascistic tendencies whilst the “Pitt Rivers” necronym remained his academic affiliation for nearly two decades. By designating all culture as fascist, he blackmails his readers into admitting that they, unlike him, secretly venerate the spoils of death.

Yet Hicks declares that the arc of history has bent towards justice under his watch. But what he is concerned with is not history but historiography. His hubris as the UK’s ethicist decoloniser-in-chief is thus self-justifying. But without a method for interpreting historical evidence, he is unable to explain how societies today might progress. Perversely, he must resort to Fox’s argument for the forced equalisation of all cultures as the means of moral improvement. Pitt Rivers’ tool was war; Hicks’ is its feeble cultural sibling.

Every Monument is a missed opportunity because there is indisputable value in an account of Fox’s legacy, however unflattering to us. The greater miss is that Hicks’s illegitimacy as a moralist detracts from the positive aspects of the growing public engagement with what are euphemistically called “complex histories”. It also brings into question the integrity of the intellectual project that dominates the institutions.

There is an opening here for those interested in history and culture. Wishing to rescue the decolonial project from Hicks, one might remind him that the distinction between ethics and fact is not some reactionary fantasy. One case in point may be Hew Locke’s excellent 2024 British Museum exhibition What have we here?, whose art-historical indictment of the British Empire was deftly couched in the artist “just telling” his audience “stories”. The Guyanese-born Locke has not shied from taking up colonial legacies in his work for decades but has consistently resisted the institution turning his work into vapid morality tales.

Another could lie in pointing out, for example, the role of cultural activists in compelling the National Portrait Gallery to tell the full biography of the first freed slave in Britain, Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, whose remarkable story of capture and emancipation was an inspiration for advocates of the abolition of slavery. Yet the gallery’s biographical entry omitted that Diallo was himself a slave owner after his return to West Africa.

This is no gotcha because these facts have long been known, yet it illustrates the risks of disciplinary boundaries shifting with fashion. Hicks might call this “whataboutism” and miss a point clear to anyone truly interested in how cultures relate to their histories.

Pitt Rivers’ founding of the museum might have been a misguided attempt at instilling an idea of historical knowledge, wrapped in a myth of a superior “aboriginal” English culture. Hicks, by contrast, offers no inkling of its successor. What is apparent from Every Monument, however, is that it produces no monuments worth toppling.