It was over lunch at his local Buckinghamshire pub, The Jolly Cricketers, that Frederick Forsyth told me the identity of the man on whom he’d based his fictional assassin in The Day Of The Jackal.

We met, in 2021, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the publication of his bestselling book about an attempt on the life of the French president, General Charles de Gaulle.

Freddie – as he was known to all his friends and, quickly, even new acquaintances – said he met the man while covering the Biafran War in the late 1960s.

I knew from Freddie’s addictive memoir, The Outsider, that he’d grown to like only three of the scores of mercenaries he’d come across while reporting on Nigeria‘s bloody civil war: a Scot called Alec, Rhodesian Johnny Erasmus and Armand from Paris.

So which one inspired the man famously played by Edward Fox in the 1973 film, and more recently, by Eddie Redmayne in the Sky TV series? Freddie felt unable to disclose a surname – ‘I liked him; he trusted me’ – but he did reveal that it was Armand, a teetotal Corsican hitman.

‘In the Paris underworld he was a sort of settler of accounts, with the full approval of the head of the Brigade Criminelle, what we’d call the CID,’ he said. ‘If there was a turf war between two powerful gangs and de Gaulle’s minister of the interior, Roger Frey, was screaming, ‘The tourists are leaving in droves. If this could be prevented…’, Armand would slot one of the gang leaders.’

But even the French had their limits when it came to extra-judicial killings. ‘Things got too hot in Paris, so the police [said], ‘May I advise you to leave Paris for a year or so?’ That’s why he was in Biafra.’

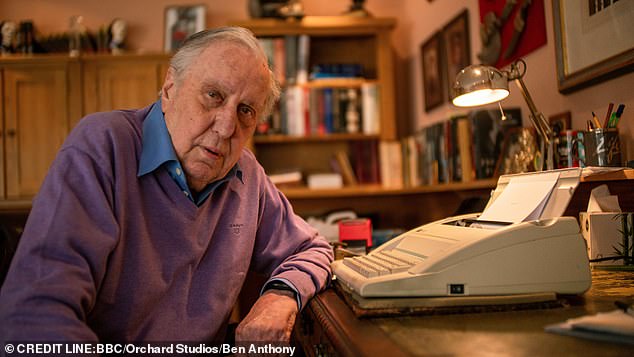

This was one of several nuggets understandably missing from BBC1’s intensely moving profile of Freddie that aired on Monday night.

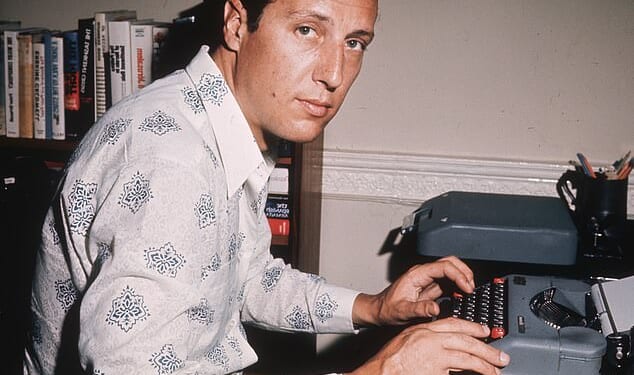

Frederick Forsyth said of the man who inspired his hit novel: ‘I liked him; he trusted me’

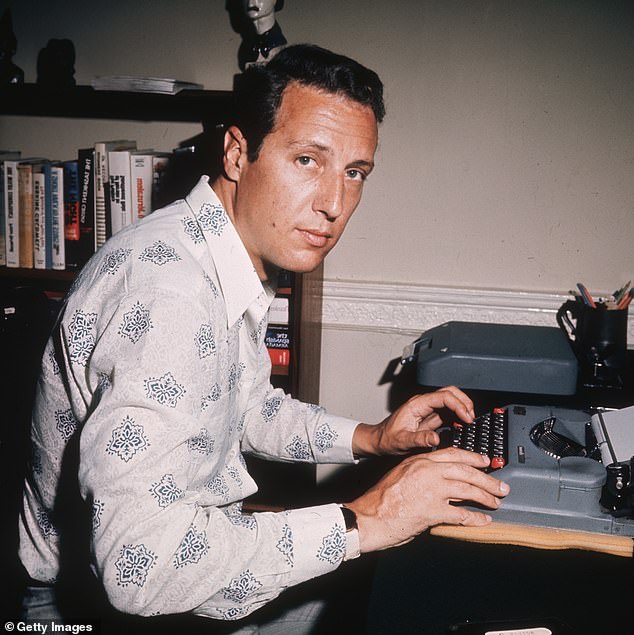

Freddie Redmayne as the highly elusive assasin in Sky’s adaptation The Day Of The Jackal

In My Own Words: Frederick Forsyth also failed to reveal the fascinating back stories to other plot lines that, in author Lee Child’s words, made The Day Of The Jackal ‘a book that broke the mould’.

It was another old Biafra hand who had introduced Freddie to the unorthodox gunsmith who assured him that, yes, a rifle could be disassembled and hidden in a crutch – the method he described in his novel. He was advised to have ‘the silencer as one tube, the barrel as another, and the breech as a third, and insert the bullet at the back, with a twisting mechanism’.

Another contact led Forsyth to a passport fraudster, who explained the devastating simplicity of his technique for obtaining one in a false identity.

In the book, the Jackal steals the identity of a boy who was born in the same year as he was, but died aged two in a car accident. And Freddie didn’t take his source’s word at face value – he decided to test the effectiveness of the method by applying for a false passport of his own.

‘I found the grave of this little boy in a churchyard in the Home Counties,’ he told me. Rather than charm and hoodwink a vicar and subsequently forge his signature, as the Jackal did, Forsyth ‘just invented a church minister in north Wales – somewhere where I thought the Passport Office wouldn’t bother to check’.

Using a thin nib, like the Jackal, he signed the requisite form in the name of the fictitious clergyman, who had supposedly known the passport applicant for a number of years. He then applied for a passport; it duly arrived.

Following the publication of his book, this method became widely known as the ‘Day Of The Jackal fraud’ and, despite being outlined in a global bestseller, the loophole was not fully shut down by the authorities until decades later.

It only remained for Freddie to find an insider who could brief him on de Gaulle’s security arrangements. He headed to Paris at Christmas 1969, and sought out someone he’d known years earlier – Roger Tessier, one of the president’s former bodyguards. In the early 1960s, de Gaulle had been the target of a Right-wing terrorist group called the Organisation Armee Secrete, or OAS, that was bent on preventing the government granting independence to Algeria, then one of its colonies.

Indeed, it was a 1962 assassination attempt on de Gaulle as he was being driven from the Elysee Palace to a nearby air base that gave Freddie the idea for his plot.

‘We talked in French,’ Forsyth recalled. ‘He was very forthcoming about how they’d kept De Gaulle alive’

Edward Fox stars as The Jackal in the 1973 adaptation

‘Tessier had retired and set up a bar,’ he told me. ‘We talked in French. He was very forthcoming about how they’d kept de Gaulle alive. But he said that if the OAS had brought in an outsider they would probably have succeeded.’

This was because the organisation was so thoroughly infiltrated by French intelligence sources that it was almost impossible to keep its plots secret. Hence Freddie’s decision to make his would-be assassin an Englishman with no previous links to the OAS.

His research complete, Freddie returned to London and wrote The Jackal in 35 days in the flat of his then girlfriend, ‘a lovely but troubled girl’ called Vanya Kewley. In the end, Freddie married twice. First to model Carrie, mother of his two boys, and then to Sandy, a scriptwriter and former personal assistant to Elizabeth Taylor.

Sandy chivvied him back to solvency after he’d been fleeced of his £4.5million share portfolio by saturnine conman Roger Levitt and left penniless at the age of 50.

Both his wives predeceased him but, by May of this year, his lungs were beginning to give out.

‘I can only walk a few yards at a time,’ he told me by phone, his voice at a higher pitch than usual.

When he died two weeks later, aged 86, it was fitting that representatives of the IPOB – the Indigenous People of Biafra – were prominent at his funeral.

This was because, while covering the war for the BBC, Forsyth became disillusioned with its ‘lies and distortions’ and quit to report from the oil-rich breakaway region of Biafra as a freelance.

In his subsequent dispatches he claimed that Nigeria’s federal government was using starvation as a weapon of war and helped to bring international attention to a famine that eventually claimed more than a million lives, many of them children.

It was because of Freddie’s reporting, said Mazi Afunwa Ukeje at his funeral, ‘that most of us here are alive’. He added: ‘He was one of those journalists who first spoke about it.

‘He showed courage. He showed that high sense of humanity. We can never forget. That’s why we are here. To honour him.’

The wake was held at The Jolly Cricketers and Amanda, its landlady, disclosed that, every week during the pandemic lockdown, Freddie would turn up with £500 in cash for her to distribute to anyone she knew was struggling.

Before and after that, she was also the person to whom he’d pass regular donations to the local charity for the homeless – always on condition of anonymity.

Freddie’s home will soon be sold, a friend told me at his funeral, and ‘razed to the ground and a huge house built there’.

Perhaps one day a blue plaque will adorn Vanya’s flat at 12 Cheyne Row in Chelsea. It should read: ‘Frederick Forsyth, RAF pilot, reporter, author, and patriot, wrote The Day Of The Jackal here in 1970 – a book born of the Biafran War.’

In My Own Words: Frederick Forsyth is available on the BBC iPlayer.

Marcus Scriven is a journalist and author who was Frederick Forsyth’s researcher on his 2018 novel The Fox.