This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

In 1982, Philip Larkin was invited to an extraordinary dinner party for Margaret Thatcher by Hugh Thomas, the historian (by then a Tory peer and chairman of the Centre for Policy Studies) at his house in Ladbroke Grove, Holland Park. Amongst the other guests were Tom Stoppard, Isaiah Berlin, JH Plumb, VS Pritchett, Stephen Spender, Anthony Powell, Dan Jacobson and Mario Vargas Llosa. The aim was to introduce the Prime Minister to leading writers, not necessarily of the Right, thereby in some measure ameliorating her perceived lack of a cultural hinterland.

Hugh was my godfather and I can vouch for the fact that his motives were admirably altruistic, but this stellar occasion seems to have been as awkward as it was misconceived. The implication that Mrs Thatcher was a philistine was not only patronising, but also unfair. Her “hinterland” was scientific: she was a product of the “two cultures” that CP Snow had lamented. Unlike her, the literary grandees present would have been hard put to hold their own in the company of a roomful of Fellows of the Royal Society.

As far as Larkin was concerned, at least, the Ladbroke Grove symposium was an ordeal. The problem wasn’t the Prime Minister, whom he “adored”, at least in theory, but the company in which he found himself. “I found I was surrounded by intellectuals!” he wrote to Andrew Motion, his future biographer.

Hard of hearing, he sat in silence. Then the PM complained about the Berlin Wall. “Surely you don’t want to see a united Germany?” he asked her. “Well, no, perhaps not,” she replied. “Well, then,” he exclaimed. “What’s all this hypocrisy about wanting the Wall down then?” (In 1989, Mrs Thatcher notoriously resisted the unification of Germany, but — as I had occasion to tell her two years later — few had done more to bring about the fall of the Wall.)

Afterwards Larkin wrote: “The Thatcher dinner was pretty grisly. Even now I shudder and moan involuntarily. M [Monica Jones, his lover] says: ‘Is it death again or Mrs Thatcher?’”

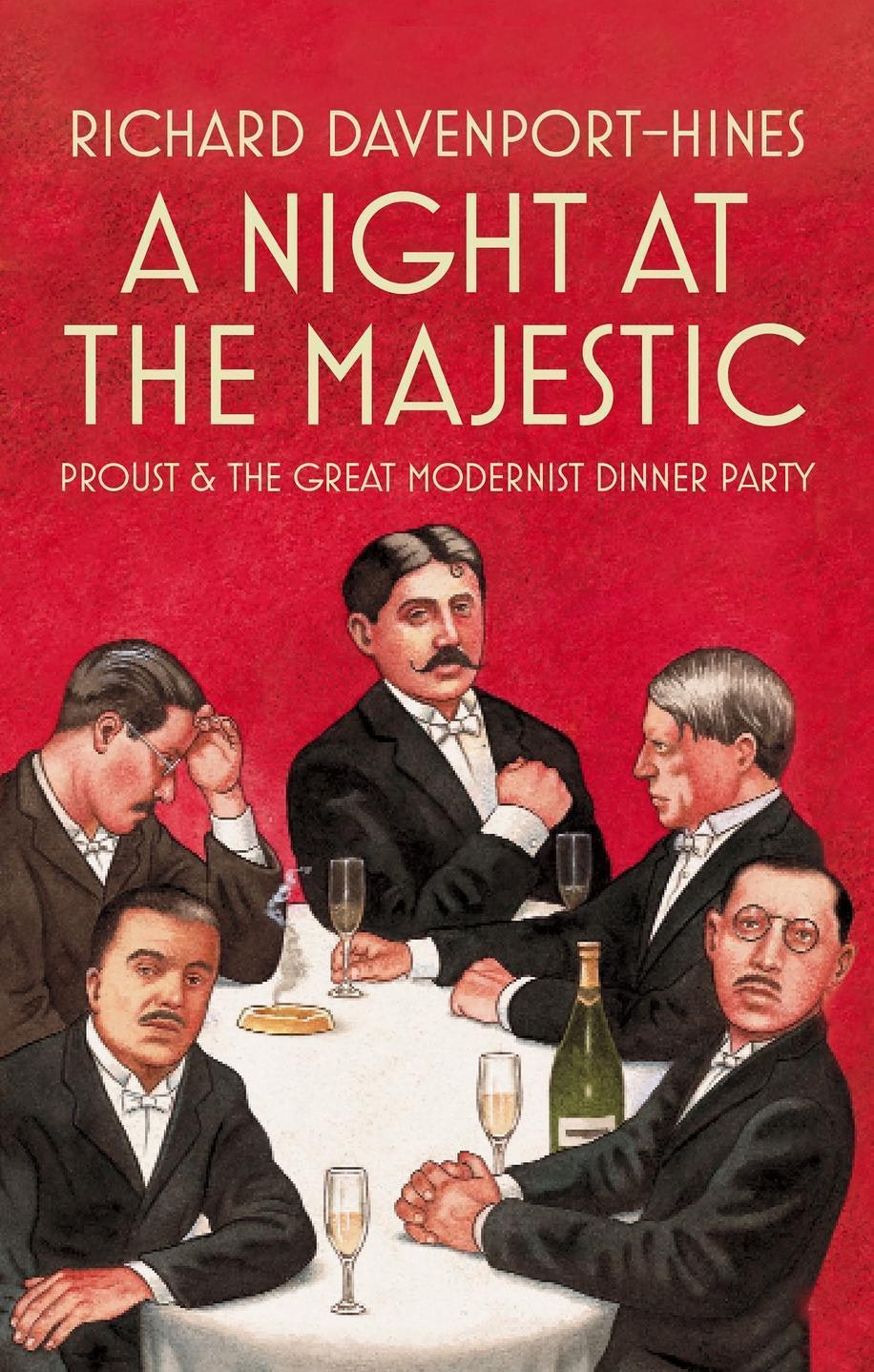

Do intellectual gatherings promote good (or at any rate conservative) causes? As this example shows, the answer is: not necessarily. True: the progress of humanity is largely a story of festivities. Food and drink are at heart of Judaeo-Christian scripture and observance, from the Garden of Eden to the Last Supper, from the Seder to the Eucharist. Plato’s Symposium is the first of countless dinner parties, culminating in the legendary Night at the Majestic (Hotel) in 1922, attended by Proust, Joyce, Picasso, Stravinsky and Diaghilev. The cultivation of conviviality became the golden thread of Western civilisation.

Our world, though, is a far cry from the coffee houses of the literati in Johnson’s London or the erudite soirées that entertained the saloons of the Victorian nobility. A magazine such as The Critic may have influence, but the British intelligentsia lacks any focal point at which such influence could be brought to bear. It’s like herding a hundred cats whilst accompanied by The Art of Fugue.

Our minds are so filled with the ephemeral joys of social media that the active pleasures of coherent conversation are yielding to this passive phantasmagoria. It deprives us of the reality of agency whilst deceiving us with the illusion of omniscience. If numbers mean anything, the gratification vouchsafed by listening to a podcast is apparently greater than that of participating in person in a discussion or attending a public meeting. Whatever the cause, the preferred option of the leisured class is to work from home.

One astonishing aspect of this usurpation of the public square by the private influencer is that the qualifications of these idols of the online marketplace are often bogus or non-existent. Joe Rogan, the most popular podcaster on the planet, is a stand-up comedian and wrestling host. Ignored by Kamala Harris, Rogan schmoozed Trump and became one of his kingmakers. This is the kind of power that elected politicians can only dream of, but few have Rogan’s gift of the gab.

He is now extremely rich and peddles his crackpot ideas to hundreds of millions.

Such charlatanry reminds me of Chaucer’s Pardoner. A medieval audience was swept away by his preaching, impressed by his fake relics and willing to pay handsomely for the forgiveness of their sins. Neither monk nor priest, just a conman, he relieved his disciples of their guilt and their cash.

At the end of Chaucer’s tale, the Pardoner offers the pilgrims’ Host a chance to kiss his relics. To which the innkeeper replies that he has no intention of kissing “thyn old breech … though it were with thy fundement depeint” (stained with his excrement).

Instead, he threatens to castrate the Pardoner’s “coillons” (testicles) and enshrine them in “an hogges toord”. No violence actually takes place: the Knight intervenes, and the pilgrims’ merriment resumes. But if only some of our Podcaster-Pardoners were given their just desserts, too.

In The Canterbury Tales, the good cause to which everything is subordinated is the pilgrimage to St Thomas Becket’s shrine. Later, it might be a campaign, such as the abolition of slavery. These were life-changing and sometimes lifelong commitments.

Today, a cause is just as likely to be an exercise in identity politics: preening narcissism masquerading as global ethics. The iconoclasm of the Reformation was at least sincerely based on theological principle: such images were deemed to transgress against the ban on idolatry in the second Commandment. By contrast, the dousing of the National Gallery’s Van Gogh with tomato soup or the slashing of Trinity College Cambridge’s Arthur Balfour portrait is a perverse form of performance art, in which the targeted objects are mere collateral damage.

Such vandalism of public collections and colleges gives the perpetrators a sense of their own importance. Whatever causes they espouse are secondary to starring in their own show, magnified by social media. An essential element of the stunt is its manifestation of the impotence of authority.

I imagine that all these activists consider themselves, if not intellectuals, then at least intellectually superior to their foes. Perhaps the pre-eminent debunkers of such pseudo-intellectuals were two close friends: Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis. They belonged to a phase in postwar British life when clever boys from modest backgrounds mocked and exposed the irreparable damage that private privilege and progressive politics had done to the beauty and conviviality of an older England.

As an undergraduate in wartime Oxford, Larkin had been an ardent admirer of Auden, “the first modern poet”. Yet few have torn down their idols with such satisfaction as Larkin did in his 1960 review essay “What’s become of Wystan?” Auden had become “too verbose to be memorable and too intellectual to be moving”.

Larkin moved in for the kill: “He has become a reader rather than a writer.” Then comes the coup de grace: “Auden, never a pompous poet, has now become an unserious one.”

Having joined the Communist Party as an undergraduate at St John’s, Oxford, Kingsley Amis had been somewhat more politically committed than Larkin. But his flirtation with Marxism did not get in the way of his emergence as the best of an impressive crop of postwar novelists. It was Amis who created the English campus novel with Lucky Jim (1953): less ideological (but wittier) than such American counterparts as Mary McCarthy’s The Groves of Academe.

As a parting shot at his ex-comrades, Amis set out his critique of the psychopathology of political activism in a Fabian pamphlet, Socialism and the Intellectuals. This slim tract, published in January 1957, marks the origin of his transformation into the familiar conservative curmudgeon of later life. He describes “the local Labour party meeting on Suez which, breaking a habit of nearly fifteen years’ standing, I went so far as to attend, vowing to join the party immediately afterwards. Within a quarter of an hour I had silently released myself from my vow. I had forgotten what political meetings were like”.

Amis is still enough of a Labour Party man that “any right-wing sentiment in the mouth of an intellectual (or anywhere else) is likely to annoy me”. But what annoys him more is “the professional espouser of causes, the do-gooder”, who pretends not to be motivated by self-interest. His conclusion is heavy with irony: “How agreeable it must be to have a respectable motive for being politically active.”

The Critic can, perhaps, provide such a respectable motive for young political thinkers — and the last person to find conviviality amiss was Amis. Whilst the “convening power” even of an indubitably highbrow organ is easily exaggerated, the difficulty of the task does not render the effort to rally those of a moderately conservative disposition any less worthwhile. On the contrary: the darker the times we live in, the more necessary it is that we should not cease from mental fight nor let the pen sleep in our hands.