I have written two articles for The Critic on the Boriswave, the first back in June 2025 after the Government released the immigration white paper.

The second was in September 2025 after Reform UK announced that if elected they would abolish Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR), including rescinding it retrospectively. This was welcome news, but there was one potential flaw with Reform’s proposal — if Labour didn’t make the ILR changes retrospective detailed in the immigration white paper, then by the time of the next general election, much of the Boriswave could already have British citizenship and would be immune from Reform’s proposal.

The Boriswave started in 2021 when the post-Brexit immigration system was implemented. Numerous salary, language and qualification requirements were relaxed, as well as new visa routes introduced — most notably the health & care worker visa — which resulted in a peak in net migration of 944,000 in the year-ending March 2023.

For migrants, obtaining ILR is remarkably easy — if a migrant meets the 5-year qualifying mark, can pay the fee and they don’t have a major criminal record, they are more than likely to receive it. In recent years, the ILR grant rate has stood at over 98 per cent.

In November last year, the Government released the earned settlement consultation and accompanying policy document. After months of non-answers from ministers and contradictory media reports about whether the changes would apply retrospectively, we finally had the answer:

Crucially, for these and every other group mentioned here, we propose to apply these changes to everyone in the country today who has not already received indefinite leave to remain. This would mean that those who are due to reach settlement in the coming months and years would be subject to the new requirements for earned settlement, as soon as our immigration rules have changed.

The consultation closes in February 2025 and, according to the Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood, the changes to ILR will be implemented from April 2026:

The shadow Home Secretary asked a specific question about when the changes will come into effect. The 12-week consultation will end in the middle of February, and we anticipate making changes and to begin the phase-out once the changes are adopted from April 2026. As he knows, the immigration rules usually change twice a year every year, and that is when we will begin making some of those changes. Some could require technical fixes and solutions that may take a little longer, but the intention is to start from April next year.

We will have to wait and see if the Government implement the changes as specified and hope nothing gets watered down. However, assuming the changes all go ahead as planned and outlined in the policy document, this should prevent the majority of the Boriswave from settling before the next election. It makes clear the Government’s intention is to reduce the projected number of ILR grants — thus offloading the decision as to whether Britain would like this cohort of migrants to settle or not to a future Government.

The Home Office estimates that under current ILR rules, from 2026 to 2030, between 1.3 million and 2.2 million migrants would settle. The number of grants by year and route for the central forecast of 1.6 million is outlined on page 31 of the policy document.

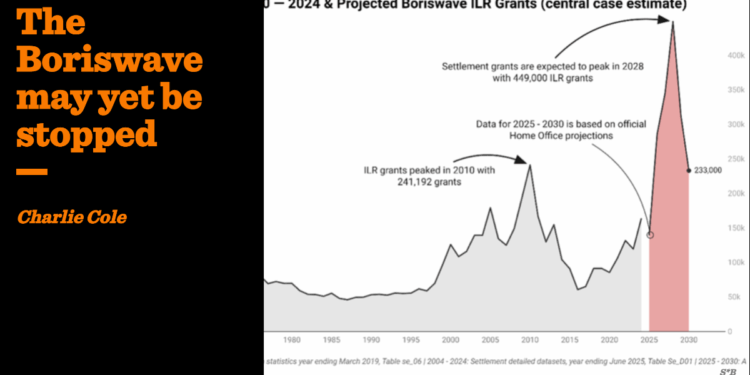

These numbers in isolation don’t show the true scale of the Boriswave obtaining ILR. Below I’ve created a chart showing the number of settlement grants from 1960 to 2024, plus the number of projected ILR grants between 2025 and 2030, under the central estimate where 1.6 million migrants settle, which is highlighted in red.

Between 1960 and 2024, the Home Office issued north of 5.6 million settlement grants, peaking at 241,192 in 2010. If we take the central estimate where 1.6 million settle between 2026 and 2030, this will represent 29% of settlement grants from 1960 to 2024 being issued in the span of just 4 years.

The policy document also mentions high case and low case scenarios, where 2.2 million and 1.3 million migrants settle respectively, however no further details are included and no break down on the number of grants by year or route is provided. I wanted to know what these looked like, so after waiting a month, I was able to obtain the high case and low case estimates via a Freedom of Information (FOI) request, which breaks down the high case and low case estimates by year and route. Here is the Home Office response.

The high case scenario results in 351,000 settlement grants in 2026, 456,000 grants in 2027, 620,000 grants in 2028, 418,000 grants in 2029 and 304,000 grants in 2030. Here’s what the high case scenario looks like.

The number of grants peaks in 2028 with 620,000 grants, completely dwarfing the 2010 peak. If this scenario was to occur, the high case scenario would represent 38% of ILR grants issued between 1960 and 2024 being issued in just 4 years.

The low case scenario results in 229,000 settlement grants in 2026, 276,000 grants in 2027, 359,000 grants in 2028, 250,000 grants in 2029 and 186,000 grants in 2030. Here’s what the low case scenario looks like.

The number of grants peaks in 2028 with 359,000 grants, which still dwarfs the current 2010 peak. If this scenario was to occur, the low case scenario would represent 22% of ILR grants issued between 1960 and 2024 being issued in just 4 years. Even under the low case scenario, the 2010 peak would be exceeded in 2027, 2028 and 2029.

Back in February 2025, The Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) released a report titled Here To Stay? Estimating the Scale and Cost of Long-Term Migration, this report estimates the number of migrants who will settle, with estimates ranging from 742,000 to 1.2 million and lifetime costs ranging from £168 billion to £241 billion, with the central estimate being that 801,000 migrants will settle, with a lifetime net fiscal cost of £234 billion.

However, it seems the CPS may have been too conservative. The date ranges between the CPS and Home Office projections don’t match exactly (although they are similar). But what’s most notable is how many more migrants the Home Office expects to settle than the CPS; even the low case Home Office estimate has more migrants settling in the UK than the high case of the CPS, which it called the “New Paradigm”. The Home Office central estimate has double the number of migrants settling than the CPS.

If the CPS estimates 801,000 Boriswave migrants settling poses a £234 billion lifetime net fiscal cost, using highly optimistic Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) assumptions that migrants arrive age 25 and bring no dependants (something which we know to be categorically false post-Boriswave) then imagine the fiscal costs if 1.3 or 2.2 million migrants were to settle in the UK.

Many people, myself included, had doubts about whether Labour would apply these changes to migrants already here. Thankfully, we were wrong. The Boriswave clearly represents such a massive cost that even Labour is compelled to address it. Its reversal is within reach.