The Department of Health has released the latest childhood obesity figures. They are as worthless as ever.

A huge amount of effort goes into weighing and measuring children in their first and last year of primary school so that these statistics can be collated. Last school year, the National Child Measurement Programme used data from 1,145,893 children. And yet all we have to show for it are “obesity” figures that defy belief and cannot be used to compare the UK to other countries. They have no relationship to the clinical definition of obesity and include many thousands of children who are demonstrably not fat. For what it’s worth — which, as I say, is nothing — the Department of Health reckons that 10.5 per cent of Reception age kids (4-5 years) and 22.2 per cent per cent of Year 6 kids (10-11 years) were “living with obesity” in 2024/25.

I have explained before the glaring problem with these statistics. Putting it as simply as possible, when a few British academics became interested in childhood obesity in the early 1990s, they needed a definition. They couldn’t use the adult body mass index (BMI) thresholds because children have a different fat-muscle ratio, and they couldn’t set a threshold based on health risks because children rarely suffer from obesity-related diseases. The sensible approach would have been to have clinicians examine children and take a note of the BMIs of those who were deemed to be obese. Instead, they did it on the cheap, looking at school tailors’ records from the 1970s and 1980s to estimate how many children were usually large at a time when childhood obesity was assumed to have been quite rare. They then assumed that 2 per cent of children were obese in the 1980s, based on little more than the fact that 1 per cent of 18 year olds had been obese in that decade. The 98th percentile thereby became the threshold for childhood obesity, and any child who had a BMI that would have put them in the top two per cent in the 1980s was classified as “living with obesity”.

This elaborate methodology introduced all sorts of problems. It was based on a lot of guesswork and some of the assumptions were questionable. Why, for example, would you assume 2 per cent of kids were obese if only 1 per cent of 18 year olds were? We know that obesity rates rise with age. Nevertheless, this became the official clinical definition of obesity worldwide and doctors were given a chart showing what was believed to be the distribution of BMI among children at different ages in the 1980s to help them make a diagnosis. Devised in 1995, this came to be known as the UK90 growth reference chart.

The system went from being dubious to outright useless when the Department of Health started collecting data on childhood obesity at the national level and inexplicably dropped the obesity threshold from the 98th to the 95th centile. This rested on the implicit assumption, which was completely without evidence, that 5 per cent of kids were obese in the 1980s. Since this was almost certainly not true, dropping the threshold was bound to create false positives and exaggerate the scale of the problem, but despite the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence stating that the 98th percentile should be used, the Department of Health has stuck with it ever since.

From the outset, moving the goalposts produced statistics that were hard to swallow. When the first national survey was done in 1995, 15 per cent of 11-15 year olds were reported to be obese, a threefold increase on what the government now assumed to have been the rate in 1990. When children reach the age of 18 and start to be measured using the normal, adult definition, a third of them magically achieve a “healthy weight”.

It is a preposterous sham but it allows politicians and “public health” mandarins to sombrely repeat the factoid that one in ten children arrive at primary school obese and “almost a quarter” of them leave primary school obese. They sometimes gild the lily further by using the meaningless category of “childhood overweight” (which uses the 85th percentile as its threshold) to claim that “more than one in three” kids are too fat by the time they leave primary school.

The reality is that the UK has been left with a system that means that “we currently have no way of determining the true prevalence of obesity at different ages”, as one paediatrician puts it. Everyone who understands how arbitrary the childhood obesity measure is knows that it overcounts the number of fat children. The only question is by how much.

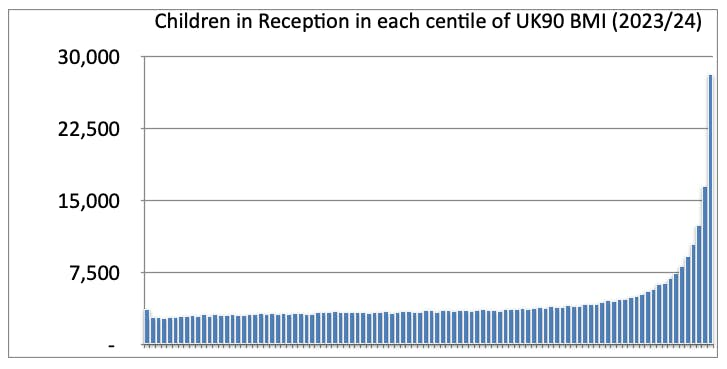

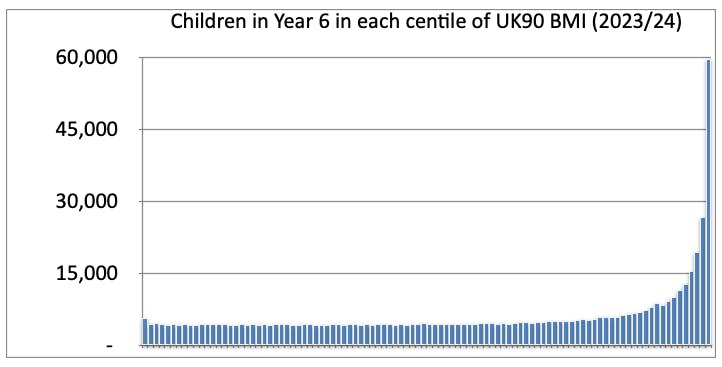

Now we have the answer. The stat nerds at Full Fact have obtained the data showing the full BMI distribution of kids in Reception and Year 6 in 2023/24. It is shown below for the first time.

These graphs show how many kids would have been in each percentile in the 1980s (according to the academics who devised the UK90 chart). In the 1980s, the graph would be completely flat with 1 per cent of the kids in each of the 100 percentiles. As you can see, the line is more skewed today with a large number of children at the high end of the scale.

This indicates a real increase in the average weight of a lot of school children, but the rise has been nowhere near as large as the official statistics suggest. There were 560,720 Reception age kids measured in 2023/24 of whom 31,208 were above the 98th percentile. Those children meet the clinical and international definition for childhood obesity and make up 5.6 per cent of the total. Officially, however, the rate was 9.6 per cent (and has risen to 10.5 per cent today). By dropping the threshold to the 95th percentile, the Department of Health conjured up 22,874 children who are supposedly “living with obese” despite not being fat. The childhood obesity statistic has therefore been inflated by 74 per cent.

There were 606,863 children Year 6 children measured of whom 86,426 were within the range of the clinical definition of obesity. This is 14.2 per cent but the official figure was 22.1 per cent because dropping the threshold caused another 47,649 children to become “obese”. The childhood obesity statistic was thereby inflated by 55 per cent.

Even using the 95th percentile creates a lot of false positives, as thousands of bemused parents who have received a letter from school telling them that their skinny child is obese can attest, but that is a story for another day. The big story is that we have been lied to about the scale of child obesity for decades. I recommend reading Full Fact’s excellent article about this and hope you will bear it in mind when you see the usual hysterical coverage of the latest batch of fraudulent statistics today.