As the power of gene editing becomes more advanced, ideas that once seemed like science fiction are rapidly becoming a possibility.

Now, a leading expert on human gene engineering has warned of what might happen if these technologies are not brought under control.

From half-rat-half-mouse hybrids to primates with human genes, scientists will soon be able to combine the genes of different animals and humans to create ‘chimaeras’.

But if limits aren’t placed on research, scientists may soon go beyond combining existing animals to create new enhanced species and even new types of humans.

That means animals and humans in the future could have abnormally boosted growth, powerful new senses, and even radically enhanced intelligence.

This month, scientists from all around the world will gather at the Global Observatory for Genome Editing International Summit to discuss how these technologies could ‘alter what it means to be a human being’.

Chairing a key panel on the ‘Limits of Engineering’ will be Professor Krishanu Saha from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, who told MailOnline that scientists need to act now to put limits on what gene modifications should be allowed.

Professor Saha says these technologies have already ‘raised some challenging questions about human integrity’.

A leading bioengineer warns what could happen if limits are not placed on gene editing technology. Already, scientists have developed ways of creating hybrid animals called ‘chimaeras’, such as half-mice-half-rat hybrids. Pictured: AI-generated Impression

Hybrid animals

One of the most surprising ways in which genetic engineering might radically reshape animals is through the creation of new hybrids called ‘chimaeras’.

Professor Saha says: ‘A chimaera would have portions of its body arising from two different sources.

‘For example, part of the organism arises from an animal, and the other part comes from a human.’

This can be done by inserting the genes from one animal into the genome of another or by inserting stem cells, cells with the potential to become any type of tissue, into the organism directly.

Even someone who has received a bone marrow transplant is technically a chimaera, because parts of their body come from a different organism.

But the first true artificial chimaera was produced in 1989 by scientists at the University of California, Davis, who combined goat and sheep genes to produce a creature dubbed the ‘geep’.

However, in the future, Professor Saha says that scientists may be able to go even further.

In 1989, scientists at the University of California, Davis, made the first chimaera by combining goat and sheep genes to produce a creature dubbed the ‘geep’. Pictured: A geep bread on a UK farm in 2014

‘There’s been some proof-of-concept experiments where they’ve essentially cut out a gene that would normally lead to making a pancreas in a rat, and then they transplanted normal mouse cells into that rat embryo,’ he says.

The resulting organism’s pancreas is entirely replaced with one from a different species, creating a half-mouse-half-rat hybrid.

Professor Saha says: ‘This is a way to potentially make large portions, if not an entire organ, from another species.’

Human-animal chimaeras

Perhaps a more alarming prospect is that these techniques could be used to combine the characteristics of humans and animals.

Although Professor Saha says scientists are yet to prove that techniques which work for mice and rats would work for humans or primates, this is an active area of research.

Scientists are interested in creating animals with human-like characteristics because they could be extremely useful in medical testing.

Instead of subjecting humans to medical trials, we might be able to breed animals that have human organs or diseases which scientists want to study.

Scientists have also begun to make human-primate chimaeras for medical testing. In the future, these chimaeras could have entire organs from humans inside primate bodies. Pictured: AI-generated Impression

Some researchers have put forward proposals to create monkey-human chimaeras which have a human gene causing them to develop Parkinson’s disease or muscular dystrophy.

While these would be extremely valuable for science, Professor Saha says this area of research is a ‘grey zone’ and a ‘place where we’d like to discuss what the appropriate limits are’.

He adds: ‘When you think that there could be not only one or two but hundreds and maybe thousands of these animals; that, to my mind, is an unsettling idea.’

However, research that is already actively taking place is also starting to raise serious questions about the limits of genome editing.

For example, in 2008, Brazilian researchers engineered a mouse capable of producing human sperm.

This raises the unsettling prospect that a normal human child could be the offspring of mice engineered to produce male and female gametes.

Likewise, scientists have taken human neural stem cells, cells with the potential to form brain tissue, and implanted them into a mouse embryo.

In 2016, a team of scientists from Nebraska found that these human cells were able to colonise the brain and spinal column of a mouse, creating a mouse which had a ‘humanised’ brain.

Scientists have created mice with ‘humanised brains’, raising the concern that these chimaeras may develop consciousness. Pictured: AI-generated Impression

In one study, scientists were able to give mice human neural support cells called glial cells which were though to improve the efficiency of the mice’s brains.

Professor Saha says that, while these experiments still have serious technical challenges to overcome, this process raises a big question for bioethics.

He asks: ‘When there have been mixtures of human cells that contribute broadly to an animal nervous system and you have a large fraction of the brain arising from the human stem cell, are we worried that that mouse now has a human consciousness?’

Professor Saha doesn’t believe that any of these current experiments could be considered conscious, but warns that this is something scientists need to properly consider.

Enhanced animals

But combining species that already exist isn’t the only way scientists might be able to change animals in the future.

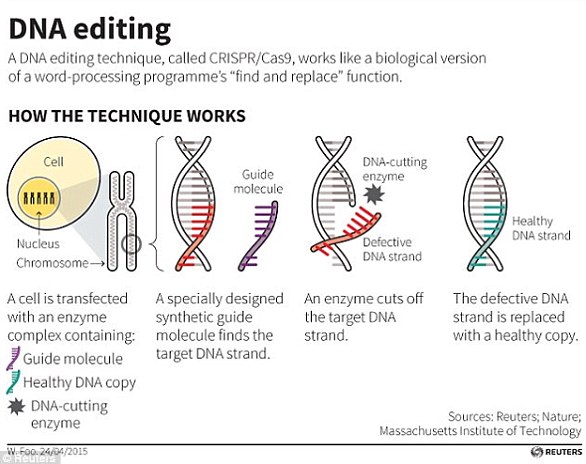

Using gene editing tools like CRISPR, scientists are able to remove or insert certain targeted genes.

By changing sets of targeted genes at the same time, researchers can create animals with new physical characteristics.

Using gene editing techniques, scientists can create new species with specifically selected traits. This is how Colossal Biosciences was able to ‘de-extinct’ the dire wolf (pictured)

By inserting new genes and deactivating others, researchers can drastically modify the features of some animals. This animal is a ‘woolly mouse’ created by Colossal Biosciences, engineered to have features found in woolly mammoths

Experts say scientists will be able to use genetic engineering to produce ‘uninhibited growth factors’ leading to larger, faster-growing livestock. Pictured: AI-generated Impression

Earlier this year, for example, scientists at Colossal Biosciences used this approach to ‘de-extinct’ the dire wolf.

What they created was not really the dire wolf which roamed the Earth during the last ice age, but a new hybrid species combining wolf and dire wolf-like traits.

Professor Saha says that if limits are not put in place, scientists might use gene editing techniques to pursue ‘performance-enhancing types of modifications’.

In livestock, this could be used to produce ‘uninhibited growth factors’ which lead to larger and faster-growing species.

In 2018, scientists targeted two genes in pigs which controlled the production of growth hormones, creating pigs which grew up to 13.7 per cent faster.

Likewise, scientists have also used genetic modification techniques to create faster-growing salmon species for intensive farming.

Some scientists have begun to suggest that genome editing could be a solution to global food shortages, producing healthier, more resilient, and more productive animal species.

But Professor Saha warns that some researchers are not content with using these enhancements on farm animals.

Genetic engineering could be used to give humans enhanced sensory capacities, such as the ability to see in light beyond the visible spectrum. Pictured: AI-generated Impression

In the future, some scientists want to use genome editing to push the human species forward in bold new ways.

‘Some of the examples that have come up include intelligence, eye colour, skin colour, and reduced need for sleep,’ Professor Saha says.

He also adds that scientists might try to give humans ‘enhanced sensory abilities beyond what you would see in the normal population’.

This could mean allowing humans to access light and sounds beyond normal human detection or giving them entirely new senses, like the ability to detect electric fields.

It is in this area that the greatest caution is needed, and scientists will need to carefully delimit what kinds of genome editing are considered acceptable.

For example, Professor Saha points out that helping people maximise their healthy lifespan is probably acceptable, while ‘the project to live up to 200’ is much more contentious.

Artificial animals

Going forward into the far future, scientists might be able to go even further beyond the constraints of nature.

Researchers have made advances in creating synthetic embryos from collections of cells. This could enable the creation of artificial species or even synthetic humans. Pictured: AI-generated Impression

One of the key focuses of Professor Saha’s upcoming panel will be on the creation of ‘synthetic embryos’.

These are ‘clusters’ of cells that have been reprogrammed to have ‘broad potential’, meaning they can grow into any tissue in the body.

In the lab, these clusters of cells have been able to develop into something that grows in ways almost identical to natural embryos.

Some synthetic human embryos have even begun to show ‘features of biological humanness’ such as beating hearts.

Professor Saha says that ‘some biologists and engineers’ think it is possible to develop these embryos into fully functioning organisms.

That raises the alarming possibility of creating synthetic animals with precisely engineered genomes or even creating synthetic humans.

Professor Saha says: ‘The definitive experiment a developmental biologist would like to see is to transplant that embryo into a womb and see if the baby or foetus develops normally.

‘But that experiment, I believe, is thought to be irresponsible by many in the field.’