A teenage girl who got PTSD after being given a drug-laced vape by older boys at a £34,000-a-year private school has won a £145,000 payout.

Irune Pedrayes was only 14 and in her first weeks at the £34,000-a-year Buckswood School, near Hastings, East Sussex when she was supplied with vape liquid containing the stimulant mephedrone by senior boys at the school.

Miss Pedrayes, now 20, told a judge earlier this year it led to a weekend of drug use and that she spent Friday to Sunday vaping the Class B controlled substance and drinking with others on the rugby pitch at the school.

But the binge landed her in hospital after she suffered an extended ‘psychotic outbreak’ for which she blames the school’s alleged lack of safeguarding – a claim denied by its lawyers.

Her parents were not told about the incident and the breakdown continued for weeks until she left Buckswood to return to her native Spain, where she received antipsychotic medication.

She has now won a £145,000 compensation payout from the school after Judge Geraint Webb KC found the institution ‘negligent’ in failing to inform her parents.

Rather than letting them know she had been taken to hospital in a ‘psychotic’ state, Buckswood led them to believe she had just been vaping and the hospital trip was for an unrelated infection.

Giving judgment, Judge Webb said the school’s actions ‘fell below the requisite standard of care’.

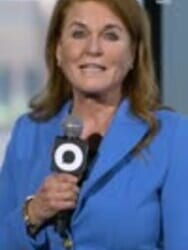

Irune Pedrayes, pictured outside London’s High Court earlier this year, a teenage girl who got PTSD after being given a ‘drug-laced vape’ at a £34k-a-year school has won a £145k payout

But he went on to clear Buckswood of accusations of being soft on drug use and of having failed to look after Miss Pedrayes in respect of her additional needs as a challenging pupil.

Sitting at the High Court in London earlier this year, Judge Webb was told that she had suffered with ‘psychological problems’ while in Spain, where she failed a year at school before moving to the UK.

Her behaviour at Buckswood – a private boarding school for children aged 11 to 19 which calls itself a ‘global school in the heart of the British countryside’ and claims in promotional materials to offer a ‘safe, supportive and family-like atmosphere’- was challenging, with repeated detentions.

She was ‘gated’ – confined to school grounds at the weekend – at the time of the drug incident.

Her barrister Meghann McTague said that, during a weekend in September 2019, Miss Pedrayes had been supplied with ‘magic’, a vape liquid containing the Class B drug mephedrone, which also goes under the street names ‘meow-meow’ or ‘m-cat’, by boys in upper sixth (year 13).

‘The claimant spent that whole weekend – Friday, Saturday and Sunday – consuming a Class B drug that was supplied to her by older boys at the school, and drinking alcohol that was also supplied to her,’ she said.

‘Nobody noticed, despite attending mealtimes and at bedtime, that she was high all weekend.’

The school accepted that, due to her drug intake, Miss Pedrayes suffered a ‘psychotic’ incident, which led to her being taken to hospital on the Monday.

Buckswood School, pictured, is a private boarding school for children aged 11 to 19 which calls itself a ‘global school in the heart of the British countryside’

She complained of visual hallucinations, sensations of deja vu, tearfulness and anxiety, but went back to the school without her parents being informed of the drug use.

After that, her behaviour continued to deteriorate, including a further incident of drug use, before she left the school in November 2019.

Back in Spain, she finally received treatment for her psychosis, but has been left with PTSD, heightened anxiety and a greater risk going forward of mental health problems.

Miss Pedrayes went on to sue, arguing that the school breached its first aid policy by not telling her parents what had happened that weekend.

She also alleged that the school did not seem to consider drug use ‘very important’ and that on the weekend of her binge there had been a ‘total failure of supervision’ of pupils on site.

School principal Kevin Samson told the judge that they had no firm evidence that the vape contained mephedrone or any other illicit drug at the time, and that a urine test did not show proof of any drug use.

He said the school had not told her parents about the incident after it happened because a subsequent urine test did not yield a positive result for drugs.

He also insisted that adequate supervision was in place for pupils, adding: ‘It’s not realistic to have a member of staff next to every child 24 hours a day.’

School principal Kevin Samson, pictured at the High Court, told the judge that they had no firm evidence that the vape contained mephedrone or any other illicit drug at the time

Giving judgment, Judge Webb said the school had ‘acted negligently’ in failing to inform her parents she had admitted taking ‘some drugs’ and that she had been taken to hospital to be checked after showing ‘paranoid and manic symptoms’.

Instead, the school ‘let the claimant’s father assume’ that the hospital attendance was connected with a urinary tract infection he had previously been told about.

‘Whilst the school informed the claimant’s parents that the claimant had been “vaping”, it failed to inform the claimant’s parents that the claimant had admitted taking a drug, which she identified as “magic”, via a vape,’ he said.

‘The school failed to inform the claimant’s parents that the claimant had been taken to hospital because of obvious “paranoid and manic symptoms” following the admitted use of drugs.

‘The school gave the claimant’s parents misleadingly incomplete information about this incident and about the injuries which the claimant had sustained as a result.

‘The symptoms reported by the claimant to the school nurse and recorded in the school medical records can properly be described as more than minor; they were reports of visual disturbance, paranoid and manic symptoms.

‘In their joint report the expert psychiatrists describe the taking of the “magic” over the weekend as precipitating “an episode with psychotic and manic symptoms” and this is accepted by the defendant.

‘In my judgment, it is clear that the symptoms noted by the school nurse amount to a personal injury of a type which should have been reported to the claimant’s parents as soon as possible under the school’s first aid policy.’

By not telling her mother and father immediately what had happened, the school denied the parents the chance of taking steps to make sure she was safe, he continued.

‘Apart from anything else, the claimant’s parents needed to be informed of the true facts in order to be able to make a properly informed decision, in the interests of the claimant, as to what, if any, steps should be taken to mitigate the risks of any continued drug use,’ he said.

‘It may be the case that the school formed the view that the adverse effects of the admitted use of drugs would be short term and of no real consequence.

‘However, that does not justify the failure to provide the claimant’s parents with adequate and accurate information concerning the true position.

‘In summary, I am satisfied that the school fell below the requisite standard of care, and was negligent, in failing to provide the information…to the claimant’s parents without delay.’

But he went on to clear the school of any fault in failing to prevent the drug-taking incident happening in the first place.

He said the evidence in the case was ‘not indicative of a culture of tolerance or complacency on the part of the school in relation to illicit drugs’.

‘To the contrary, the documentary evidence demonstrates the significant and persistent efforts being taken by Mr Samson, personally, to tackle the issue of older students obtaining drugs and bringing them onto the school grounds,’ he said.

‘In my judgment, the totality of the evidence does not support the conclusion that there was any systemic failure on the part of the school to take reasonable care to prevent access to drugs and/or use of drugs by students at the school, including the claimant, between September and November 2019.

‘It will never be possible, and may well be inappropriate, for a boarding school to monitor and supervise every waking hour of a student at the weekend.’

He also dismissed allegations that the school had not taken enough care for ‘vulnerable’ Miss Pedrayes as a pupil with additional needs, treating her instead as a naughty child.

‘Members of staff devoted considerable amounts of time and effort to attempting to deal with Irune Pedrayes’ poor behaviour and the underlying causes of that poor behaviour,’ he said.

‘I have seen no evidence to suggest that the punishments were unwarranted, inappropriate or that they were somehow contrary to the generalised guidance provided by the claimant’s treating psychologist.

‘It is clear from the evidence, including Mr Samson’s evidence, that the school was attempting to set boundaries in relation to the claimant’s behaviour and ensure that poor behaviour was not condoned and I have not seen any evidence to suggest that the school was negligent in the steps it took in this regard.’