THE 1970s are rightly remembered as a decade when the UK economy went badly wrong.

But now I fear Rachel Reeves is driving Britain into the same crisis.

Inflation took off dramatically and reached a peak of over 26 per cent in the autumn of 1975.

The mid-70s also saw the first major post-war recession.

Unemployment rose to around 1.5 million in the second half of the decade.

Strikes were commonplace and living standards were under pressure from high inflation and rising energy prices.

However, the most humiliating episode from this period came in 1976, when a financial crisis and a collapse in the value of the pound caused the Government to seek help from the International Monetary Fund.

Tough limits

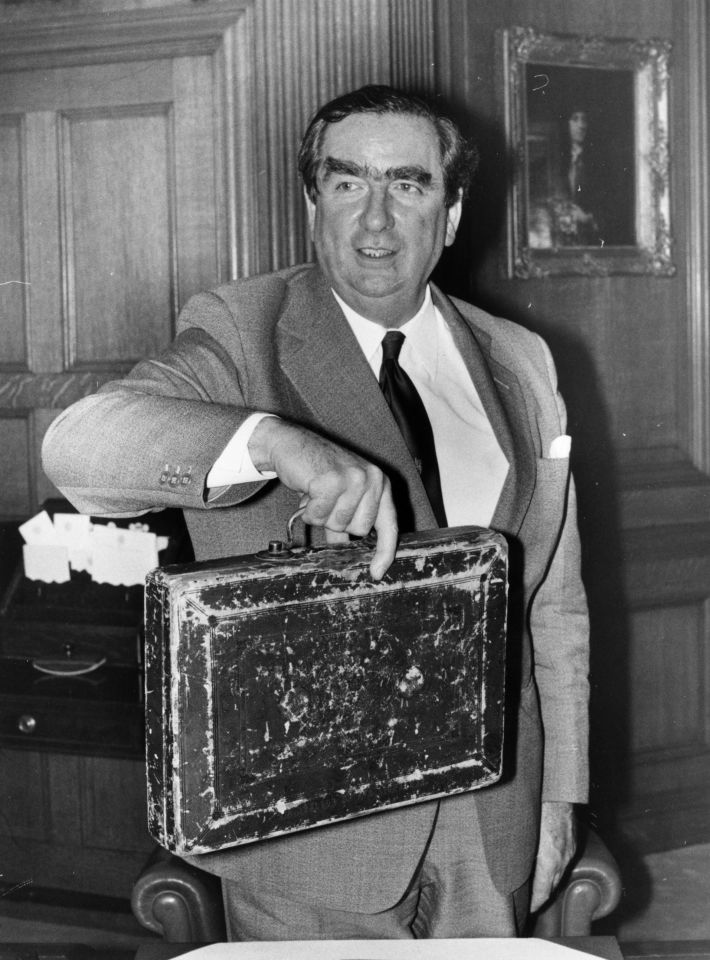

The Chancellor, Denis Healey, had been increasing government spending and borrowing to counter rising unemployment and other effects of recession.

Taxes had also been pushed up to pay for higher spending.

The financial markets lost confidence in Healey’s economic policies and the IMF was called in to provide a bailout.

Healey and his Labour Cabinet colleagues had to agree to the IMF’s conditions, which required cuts in public spending and tough limits on government borrowing.

Healey’s successors at the Treasury heeded the lessons of the crisis.

The Conservative Chancellors in the 1980s and 1990s — including Geoffrey Howe, Nigel Lawson and Ken Clarke — kept tight control of public spending and borrowing. Income tax rates came down and many business taxes were reduced.

When Labour returned to power under Tony Blair, Gordon Brown kept a tight grip on public spending and borrowing, particularly in his early years as Chancellor.

He was determined to demonstrate that there would be no return to the crisis years of the 1970s Labour government, and was rewarded by becoming the longest-serving Chancellor of the Exchequer in British history.

Fast-forward to 2025 and we find that Rachel Reeves has not heeded the lessons learned by her predecessors as Labour Chancellor

Fast-forward to 2025 and we find that Rachel Reeves has not heeded the lessons learned by her predecessors as Labour Chancellor.

She has come into office following policies remarkably similar to Denis Healey in 1974 and 1975 — before the IMF crisis.

In her first Budget, she increased public spending totals by around £100billion a year over and above the amounts set out by her Tory predecessor, Jeremy Hunt.

In this Budget, she has ratcheted up public spending even more — her increase in spending over previous Tory plans is now up to £146billion in the financial year 2027/28, a couple of years ahead.

That is about £5,000 a year extra spending for every household in the UK and a rise of about 11 per cent.

Where is this extra money going? In her last two Budgets, the Chancellor has talked about prioritising the NHS.

But her spending plans include increases for a wide range of departments — including defence, education, the Home Office and social security.

One important reason for higher spending is pay rises in many parts of the public sector, with its wage rates currently rising at nearly seven per cent, compared with 4.4 per cent in the private sector.

Pension costs are also rising as higher inflation and wage increases are expected to push up the cost of the triple lock formula for uprating pensions in future years.

Other benefit payments are also rising because the Government has had to backtrack on welfare reform and has removed the two-child cap for Universal Credit and Housing Benefit.

On top of all this comes the rising cost of debt interest, with the financial markets charging higher rates of interest for lending to the British government.

Perhaps most worrying of all is the risk that our current Chancellor ends up in the same position as Denis Healey

The UK national debt is now approaching £3trillion, which is around £100,000 for each household in the UK.

Increased public spending requires higher taxes and/or more borrowing.

As a result of Reeves’s two Budgets we are seeing both tax rises and higher borrowing.

Costs for consumers

Last year’s Budget raised taxes by around £40billion and this year the Chancellor announced tax increases totalling a further £26billion.

In addition, borrowing is forecast to be around £60billion higher this financial year and £50billion higher in future years, compared with Jeremy Hunt’s March 2024 Budget plans.

More borrowing makes it likely that both inflation and interest rates will also be higher, adding to costs for consumers and people with mortgages.

There are therefore many reasons for us to worry about the Chancellor’s higher spending plans, which she has outlined in her first two Budgets — and this is perhaps the reason Reeves kept quiet about her spending increases in last month’s Budget speech.

But perhaps most worrying of all is the risk that our current Chancellor ends up in the same position as Denis Healey, whose mid-1970s policies she is following.

A major financial crisis driven by Reeves’s big-spending and high borrowing policies may not be far away.