From the sound of traffic to spending too much time on your smartphone, there are plenty of things in the modern world that can give you a headache.

But scientists now say that some people’s pounding heads could have a far more ancient origin.

According to new research, Neanderthal genes could be the reason that some people are more prone to a type of headache-causing brain defect.

These defects, known as Chiari malformations, occur when the lower part of the brain extends too far into the spinal cord and affect about one in 100 people.

In the mildest cases, these can cause headaches and neck pain, but larger malformations can lead to more serious conditions.

Scientists previously suggested that these defects might have arisen when Homo sapiens interbred with other human species in the distant past.

Since these ancient hominins had differently shaped skulls, genes that would lead to healthy development in their species could cause malformations in modern humans.

In their paper, published in the journal Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, the researchers have now specifically identified Neanderthal genes as the origin of this condition.

If you suffer from frequent headaches, scientists say it could be your Neanderthal genes that are to blame (stock image)

Scientists say that interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals led to genes which cause headache-inducing brain defects called Chiari malformations. Pictured: A reconstruction of a Neanderthal man

The researchers suggested that the mildest form of Chiari malformation, known as CM-I, could have its roots in interbreeding between Homo sapiens and other hominins.

To understand how these might have been transferred from our ancestors’ relatives, the researchers examined the skulls of various human species.

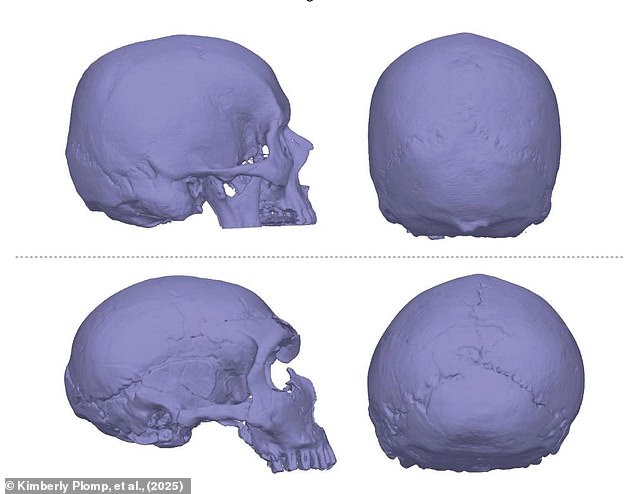

In the paper, published in Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, compared 3D models of 103 modern people with and without Chiari malformations with eight fossils from ancient hominins.

These included the skulls of Homo erectus, Homo Heidelbergensis, and Homo neanderthalensis – known as Neanderthals.

Modern humans with the CM-I malformation had a number of differences in brain shape, mainly in the regions where the brain connects to the spine.

However, when the researchers examined the skulls of ancient hominins, the only species with a similar skull shape was the Neanderthals.

In fact, the skulls of Homo erectus and Homo Heidelbergensis were actually closer to humans without the malformation.

Lead researcher Dr Kimberly Plomp says: ‘Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis are both hypothesised to be ancestors of humans and Neanderthals, so to find that they were closer in shape to healthy human crania makes the similarities identified between Neanderthals and humans with Chairi even more persuasive.

Scientists compared the skulls of Homo sapiens (top) with and without Chiari malformations to the skulls of ancient hominins, including Neanderthals (bottom)

Neanderthals shared changes in brain shape also found in people suffering from the headache-causing Chiari malformations. Pictured: A 75,000-year-old Neanderthal skull known as Shanidar Z

‘It means that the shape traits really seem to be unique to Neanderthals and humans with Chiari, and are not just part of our shared lineage.

Since the researchers didn’t do a genetic analysis, it is hard to say that Chiari-associated headaches are ’caused’ by Neanderthal genes.

However, Dr Plomp says it shows that some human skulls have shapes likely caused by Neanderthal genes, and those shapes can lead to Chiari malformations.

That doesn’t mean that every Neanderthal would have been walking around with constant headaches.

However, although their large brains might have mitigated the issue, interbreeding with Homo sapiens might have given some Neanderthals a similar problem.

Dr Plomp says: ‘So our study suggests that the malformation can happen because the shape of our brain doesn’t fit properly when our skull has some Neanderthal shape to it.

‘Potentially, if there was a Neanderthal with some modern human cranial shape traits, their brain would not fit properly either.’

Scientists believe that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals had two major periods of overlap and interbreeding.

Scientists believe that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals interbred over thousands of years, passing on their genes through hybrids such as the ‘Skhul 1’ child (pictured)

The first occurred around 250,000 years ago in what is now the modern-day Levant and lasted nearly 200,000 years.

Previously, scientists had thought that these moments of interbreeding were fleeting one-off events.

But new evidence is beginning to show that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens interbred much more frequently than scientists had previously considered.

Today, up to 45 per cent of the complete Neanderthal genome survives across the modern human population, but the distribution of Neanderthal genes is highly dependent on Geography.

This should allow the researchers to test their theory, since rates of Chiari malformations should be lower in areas with less Neanderthal DNA.

Some people in East Asia get up to four per cent of their genes from Neanderthals, while in Africa, where Neanderthals never became established, many people have no Neanderthal genes whatsoever.

If the theory is correct, rates of Chiari malformations should be significantly higher in East Asia than they are in Africa.

Ultimately, the researchers hope these findings could inform methods for treating Chiari malformations or even stop them from happening in the first place.

The paper concludes: ‘The methods would seem to have the potential to help us develop a deeper understanding of the aetiology and pathogenesis of Chiari malformations, which could in turn strengthen diagnosis and treatment of the condition.’