Fifteen years ago, only one state publicly tracked the number of students missing enough school to be considered chronically absent.

Now, 49 states publish data online about chronic absenteeism, which is generally defined as missing 10% or more of the academic year. Data has been key to tackling an attendance problem that ballooned during the pandemic to nearly a third of students. The rate of chronic absenteeism has dipped modestly in many places, but it remains elevated compared with pre-pandemic school years.

“If you don’t know that a problem exists, you don’t act on it,” says Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a nonprofit focused on reducing chronic absenteeism.

Why We Wrote This

From test scores to absenteeism, data drives much of what educators know about students and how to help them. States are now more involved in tracking trends, but with the extent of a federal role increasingly less clear, the door is opening for talk of reform.

Chronic absenteeism is among numerous data points collected by local, state, and federal education officials in a bid to improve student learning. It’s typically a behind-the-scenes task that comes to light every so often via test scores, graduation rates, and other markers of student success or struggles.

But the future of federal data collection is murky given deep downsizing at the Education Department and a proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year that slashes funding for the Institute of Education Sciences (IES). The Trump administration’s funding request for IES – the research and data arm of the department – totals $261.3 million. That represents a 67% decrease from fiscal year 2024.

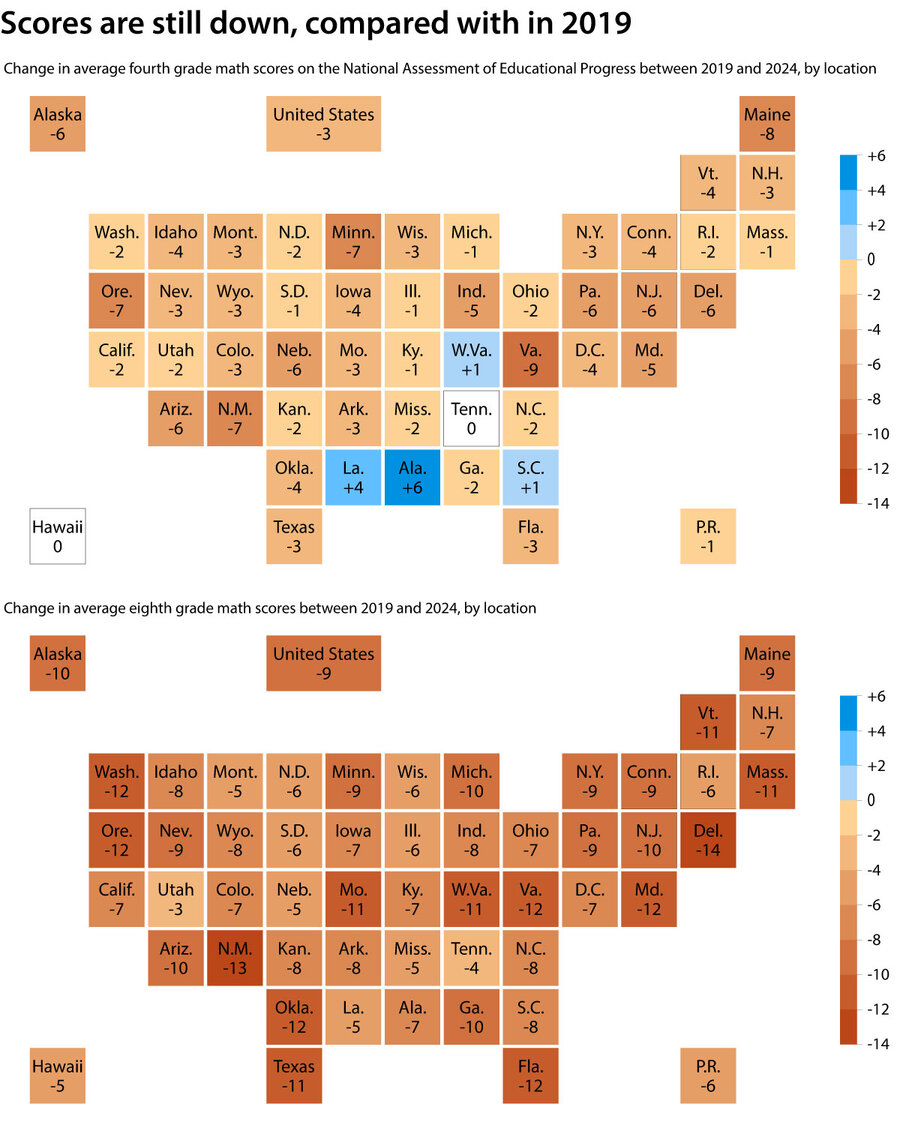

The question underlying possible congressional approval: Will this worsen education outcomes for America’s schoolchildren, who already are struggling with generational low test scores? Or could reforming the way in which data is studied jumpstart an effort to improve federal research?

The agency, in its budget proposal, framed the changes as an opportunity for “reimagining a more efficient, effective, and useful IES.”

Last month, the Education Department hired Amber Northern, from the conservative-leaning Thomas B. Fordham Institute, to lead the overhaul. The agency’s announcement also took swipes at the current iteration of the institute, albeit without supporting details.

“IES has failed to provide a clear and compelling research agenda that puts students at the center,” a press release states. “Its research contracts often prioritized politically charged topics and entrenched interests over classroom best practices and tools, even while American students experienced historic levels of learning loss following the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Requests to the Education Department asking for more details about the contracts referred to went unanswered.

Not all federal data collection is going away. The National Assessment of Educational Progress, for instance, would remain. That test offers a peek into how the nation’s fourth graders and eighth graders are faring in math and reading. In recent years, the NAEP results have shown dismal outcomes, especially in reading, and have fanned partisan flames over education policy.

Why solid data matters

The proposed funding cuts, however, have drawn skepticism despite the administration’s suggestion that improvement is the end goal.

Sean Reardon, an education professor at Stanford University, says the move could set the United States’ education system back to the 1990s or earlier, when comparable data collection was slim to none.

“It’s impossible to learn if we don’t have information about what’s going on and what’s working,” says Dr. Reardon, who is also the developer of the Stanford Education Data Archive. “We have 13,000 school districts in the country that are relatively autonomous.”

Attendance Works’ latest report urges states to continue drilling down into chronic absenteeism data to look for patterns that could lead to solutions. As far as Ms. Chang is concerned, it’s not an either-or situation.

“We should have federal data collection,” she says. “At the same time, I will say it’s also going to be now even more essential and important that states continue to collect their own data – and ideally, they continue to collect data in relatively common ways to each other.”

One group’s approach is to model how federal research should be done. The Alliance for Learning Innovation, a coalition formed in 2023, is sharing its vision on Capitol Hill later this month. The coalition’s blueprint for future federal efforts – crafted with input from dozens of researchers – promotes investing in research and innovation, empowering state and local leaders to scale proven methods, and collecting high-quality, timely data, says Sara Schapiro, executive director of the alliance.

“What’s working well in Mississippi? How can we get that going in Maryland?” she says, explaining the desire to replicate bright spots across the country. Students in Mississippi, a historically poorer state, have bucked national trends and posted stronger NAEP reading scores in recent years.

For now, Ms. Schapiro says she is “somewhat optimistic” the Education Department will rebuild core research and development functions. But that positivity is laced with a caveat.

“How much money will they actually put behind it?” she says. “Will they actually rehire some of these positions or reenvision the positions but hire enough capacity to deliver on this? I’m not sure.”

How one school uses “data day”

Nearly 700 miles away from the nation’s capital, a high school in Piedmont, Alabama, has embraced diving into numbers on the hyperlocal level. Principal Adam Clemons says Piedmont High School has created an “ACT culture” that gives students multiple chances to take the standardized college admissions test for free each year.

In this former cotton mill town situated between Birmingham and Atlanta, the 1,100-student school district is the largest employer, Dr. Clemons says. Earning a higher score on the ACT could be students’ ticket to college scholarships and greater job opportunities.

But Dr. Clemons says the data from ACT results, mock college admissions tests, and other metrics such as attendance identifies where students are excelling and which students need the most help. Roughly every five weeks, the high school has a “data day” that brings staff members together to analyze the numbers and tailor their teaching accordingly.

Data can feel overwhelming to the average person, Dr. Clemons says, and parents don’t always understand how necessary it is at levels big and small.

So the school leader has started taking photos for social media to spread the word.

“It’s not like we’re just sitting here with our feet propped up reading the newspaper,” he says. “We’re actually diving deep into the data to make the instructional changes.”