This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

The second time the bit-part player missed his cue, the movie star stormed off set. A while later, after calming down in his trailer, he sashayed back saying he was ready to go again. No need, the director told him, we already shot the scene. Huh? “I’m paid to shoot film,” the director said. “If you walk off, I’ll shoot close-ups of your double … I’m not here to jerk off.”

Welcome to the world of Clint Eastwood, where nobody, not even Kevin Costner at the peak of his early ’90s pomp, plays prima donna. Certainly Eastwood himself doesn’t. Not long before that tiff, his shadowy, feminist western Unforgiven had taken numerous awards at numerous ceremonies. Any moviemaker would have been overjoyed, but a moviemaker who had spent the previous quarter of a century being dismissed as a know-nothing “fascist medievalis[t]” should surely have been happier still.

Yet at every prizegiving Eastwood stopped being terse only in order to be taciturn. The most voluble he got was when he confessed to the Directors Guild: “I don’t know what to say. I’m not a blabbermouth.”

On screen he’s even more laconic. Most actors are on the lookout for parts with knockout speeches. Eastwood has always insisted on being the strong, silent type. Even when he was starting out, in the ’50s TV Western series Rawhide, he would tell the show’s writers and directors that they could lose most of his lines. “Don’t just do something!” he recalls a teacher at Universal Studios telling him: “Stand there!” Eastwood has stood there so long that he is as much a part of the American landscape as the Grand Canyon or Mount Rushmore.

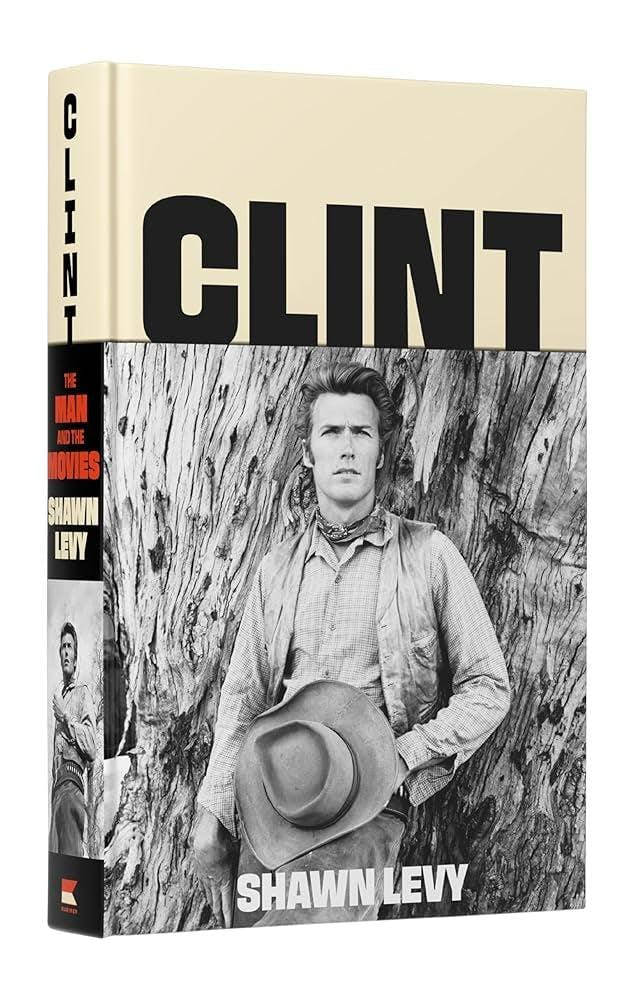

He was born in San Francisco in 1930, the son of a bond salesman knocked sideways by the Wall Street crash. The Eastwoods spent much of Clinton Jr’s youth moving from city to city, as Clinton Sr looked for work. In his meticulous and textured new biography, Shawn Levy argues that the result of this peripatetic childhood was the self-contained solitude all Eastwood’s most interesting characters incarnate.

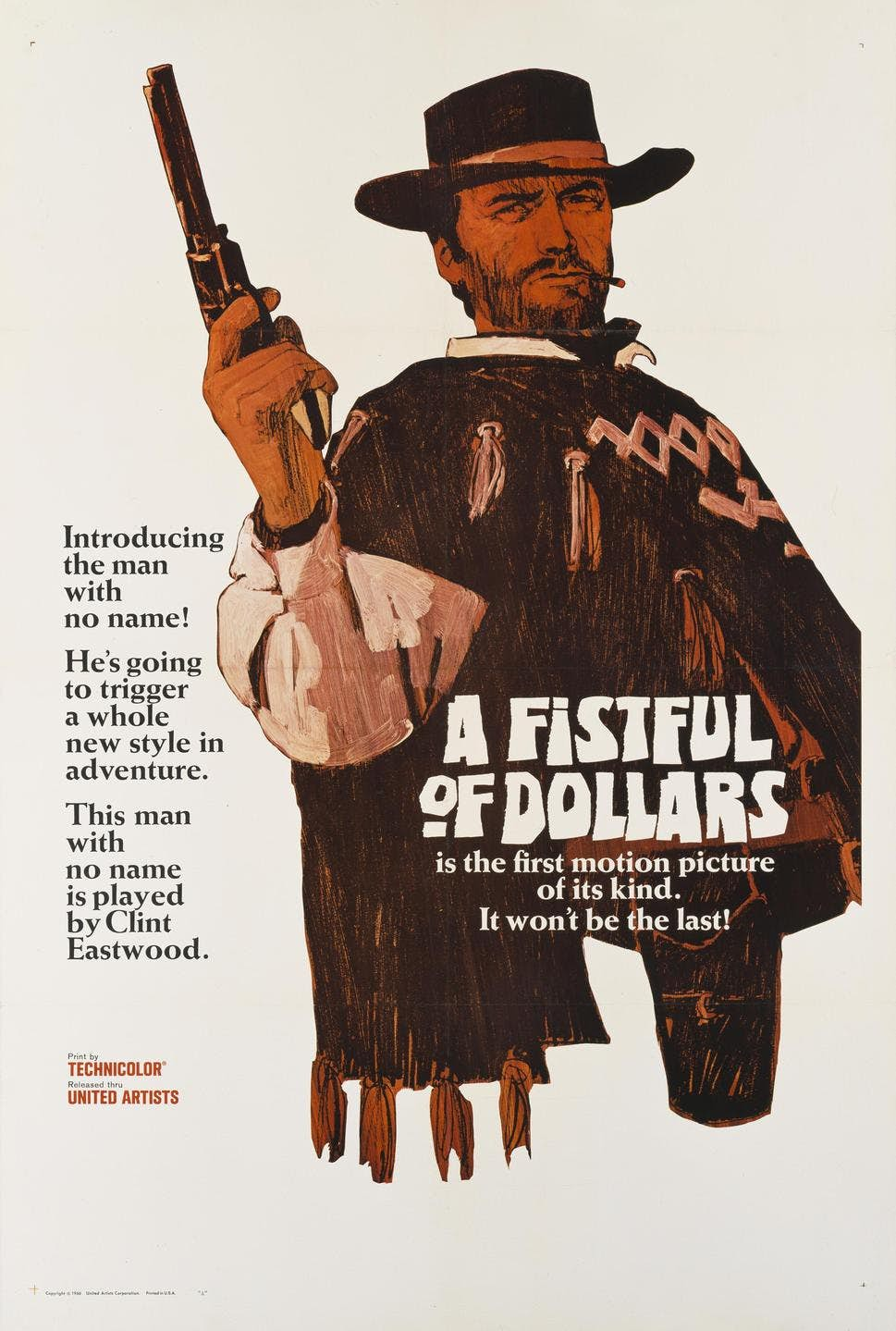

Being a TV series, Rawhide couldn’t let any one player become too important — and couldn’t, therefore, afford Eastwood the isolation he felt his persona needed. But after a few years on the show he got what turned out to be a huge break when he was invited to, of all places, southern Spain to make, of all things, an Italian cowboy movie. Graphic and gratuitously violent, with overtones of opera and undertones of Bond, Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars turned Eastwood into the ’60s emblem of fatal bad-shave cool.

Two further spaghetti westerns quickly followed — For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly — both of whose titles are wordier than anything Eastwood’s antihero is called upon to say in them. Indeed, Clint was so clipped that Leone pronounced himself fascinated by his star’s wilfully withdrawn nature. When asked what had led to his casting an unknown American in an Italian picture he would quote Michelangelo’s claim to have spied the figure of Moses in a block of marble, adding that he (Leone) had looked at Eastwood and seen “a block of marble”.

A block of marble he might have been, but Eastwood was no blockhead. Shooting the third of Leone’s trilogy, Eastwood told his co-star, old hand Eli Wallach, that he was calling it a day. “I’m going back to California,” he said. “I’ll form my own production company, and I’ll act and direct my own movies.”

Wallach cackled at the arrogance of youth, but Eastwood meant what he said. Within a year he had founded Malpaso Productions, and within a couple of years had set up, starred in and stormed the box office with his own Pop Art western, Hang ’em High. Three years later, in 1970, he directed his first picture, the sex thriller Play Misty for Me. Fifty-odd years on, Eastwood has directed 40 further films. For 2003’s Mystic River, he gave an uncredited cameo to one Eli Wallach.

There’s plenty of competition, but Mystic River might just be Eastwood’s masterpiece. It’s a noirish mystery, but it’s also, like so many of his chosen projects, a probing examination of the trials and torments of family life. Indeed, Eastwood the director has over and over again been drawn to stories — the aforementioned Misty, Breezy, The Bridges of Madison County, Changeling — that would once have been dismissed as fodder for women’s pictures.

At the same time, Eastwood the actor has been careful to keep on side the fan base he had built up with the Leone westerns. Even as he was shooting Misty he was also at work with the pulp director Don Siegel reshaping a script that would give him what would become his signature role — the liberal-loathing, bureaucrat-baiting, Magnum-massaging Harry Callahan.

There was, Levy argues, quite a lot of Eastwood in Dirty Harry. Like Harry, Clint has never been afraid of being disliked. Like Harry, he has no time for time-wasters, much less for profligacy. Like Harry, he simply wants to be left alone to get on with his work.

But don’t, Levy cautions, push the autobiographical parallels too far. Eastwood may be a Republican, but he isn’t a reactionary. For all the shooting he’s done on screen, he is in favour of gun-controls. He is pro abortion, pro gay rights, pro legalising marijuana. He is a conservationist. While in interviews he has always been keen to keep his male fans on board by bigging up his fondness for beer, in private he is almost cranky about his organic, juice-heavy diet.

Since he turned 95 earlier this year and is still making movies (incidentally, as well as directing and starring in them, he these days often composes their sombrely jazzy scores) that diet has likely done well by him. But how well, Levy is obliged to ask, has Eastwood done by the women in his life? Not ideally, he argues, though far from disastrously.

Whilst he cleaves close to the muck-raking account put painstakingly together a quarter of a century ago in Patrick McGilligan’s notorious Clint: The Life and Legend — a tale of serial skirt-chasing and one-night flings that made Play Misty for Me look like an episode of The Love Boat — Levy lays a lot more emphasis on Eastwood the reliable guy than McGilligan did.

To be sure, the number of young Eastwoods is rather greater than the number of children who have ever shared a house with their father. But he has been a good parent all the same. Indeed, as Levy points out in a footnote, Eastwood the moviemaker has a gift for directing children. Moreover, one of the major themes of his mature work (not hyperbole — it is hard to think of another filmmaker who has improved so much as his career has gone on) is that of the older man desperately seeking atonement for having failed his family.

In the end, of course, what matters about artists isn’t their life but their work. So the best news about Clint is that it is at its strongest when discussing Eastwood’s pictures. Levy is an astute critic, and he refuses to dismiss movies that suffered hatchet-job reviews or didn’t do well at the box office.

He knows that Every Which Way but Loose and Any Which Way You Can (two movies in which Clint played co-star to an orangutan) are stinkers. But his defence of even the most egregious of the Callahan series is brave and spirited, and his claims for the burgeoning moral vision in Eastwood’s westerns should have even the most sceptical detractor willing to take another look.

Truth be told, Eastwood’s work has paled these past few years. His storytelling has slackened and his performances diffused. Whilst Don Siegel once said that he’d “never worked with an actor who was less conscious of his good image”, an air of old man’s vanity has crept in.

Yes, the nonagnerian Clint still looks enviably lean and taut. But did we really need to see the 88-year-old bed what Levy calls those “comely young senoritas” in The Mule? Did we really need to witness an actress half a century his junior come on to him in Cry Macho? In Magnum Force Dirty Harry reminds his boss that “a man’s got to know his limitations”. Would that Clint had been listening.

Still, when a guy gets as old as Eastwood is and carries on turning out even half-good work we ought not cavil overmuch. After working for him on Mystic River that fiery Method actor Sean Penn called Eastwood “the least disappointing icon in American film”. Clapping Shawn Levy’s book shut, it’s hard to disagree. He isn’t here to jerk off.