This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Mountains do strange things to us. You see one, and a thought appears in your head. What would it feel like to stand at the top? Before you know it, you’re stirred into bracing action. But “bracing” means different things to different people. For most, a hike to the summit is enough. Others like to run or climb or to add further peaks. And then there are the subjects of Peter McDonald’s new book.

Peter McDonald (IPN, £15)

England’s Everest is a short, gripping history of a vanishingly narrow sporting niche: the quest to climb as many Cumbrian peaks as possible in the space of 24 hours. It’s not a complicated challenge. Each peak must be 2,000 ft or higher, you must start and finish in the same place, you cannot use GPS navigation and you must do it all on foot.

The rest is up to you. But the levels of strength, stamina, mountaincraft and grit required are so mountainous as to be beyond most imaginings. In almost 200 years, fewer than 70 people have attempted the Lake District 24-hour fell record. Fewer than 30 have held it. Yet McDonald has woven their exploits into a strangely compelling book.

The story begins in 1832, when Joseph Clark and Harrison Walker climbed Skiddaw, Helvellyn and Scafell Pike in a single day. That exhausting three-peak circuit — starting and finishing in their home town of Keswick — was retrospectively recognised as the first record. Then the strange, unquenchable human instinct for emulation took over.

Singly or in pairs, a succession of energetic oddballs asked themselves if the limits of the possible had really been reached, then strove to go just that little bit further. The first were well-heeled Victorians, hiking in heavy tweeds and stout boots. They had few paths to follow and were ill-prepared for the natural hazards of the fells. We read of would-be record-breakers lost in bogs or forced by ferocious winds “to pursue their course on all fours”. One unfortunate pair had their clothing “frozen to their backs”.

But few complained, and, every now and then, someone overcame the hardships enough to add another peak or two. By the early 20th century the record was in double figures. Challengers began to run as well as walk. They also worked out that, like mountaineers, they needed to plan their expeditions.

Dr Arthur Wakefield, who held the record from 1905 to 1922 — first with 11 peaks and later with 22 — was well qualified to do so. He was an experienced alpinist who took part in Mallory’s 1922 Everest expedition. Nor was he the last record-holder with such high aspirations. Mark McDermott, the Cheshire IT worker who held the record from 1988 to 1996, climbed Everest without oxygen in 2001. This recurrent link is one reason for the “Everest” in the title. Mainly, though, it evokes the challenge’s enormity.

In 1932, Bob Graham, a Keswick guesthouse-keeper, pushed the record so far beyond what had gone before that his 66-mile, 42-peak circuit (still known as “the Bob Graham Round”) was widely assumed to represent the absolute limits of human endurance. Graham wore plimsolls and an old pyjama top and snacked on hard-boiled eggs, jogging the downhills and “resting” on the slow uphill slogs. It would be 28 years before his achievement was matched and another year before anyone bettered it.

When they did, in 1961, another landmark was passed. Ken Heaton’s 51-peak circuit involved 29,500 ft of cumulative ascent: more than Everest. Each subsequent iteration of the record has been equivalent to going up and down the world’s highest mountain — and more — in a single day.

Today the record stands at 78 peaks (set by Andy Berry in 2023). The women’s record is 68 (Fiona Pascall, 2022). These were circuits of, respectively, 95 and 88 miles, involving 39,100 ft and 35,100 ft of ascent and (more painfully) descent. It’s impossible not to be awed by these achievements, especially if you have some experience of the agonies of running for hours on steep, rocky ground.

But these were sophisticated, modern, sponsored ultra-runners. The record-breakers whose struggles stay with you belong to a more primitive era, before ultra-running and trail-running were fashionable, globally-monetised pursuits.

There weren’t even trails, as we now think of them, when most of the book’s action takes place, and even if there had been they would probably not have shown on the rudimentary maps then in use. (Ordnance Survey “Popular Edition” maps appeared in the 1920s but were aimed mainly at motorists.) The Lake District only became a National Park in 1951. Yet for those with sufficient gung-ho spirit, none of that mattered.

McDonald’s heroes include Eustace Thomas, a middle-aged Manchester businessman whose 1922 record of 29 peaks was founded on multiple failures, and on a self-developed “system” that included a short-stepping, straight-legged gait, deliberately heavy breathing, camel-hair socks and regular ingestion of hot milk, egg, rice pudding, pears and cream.

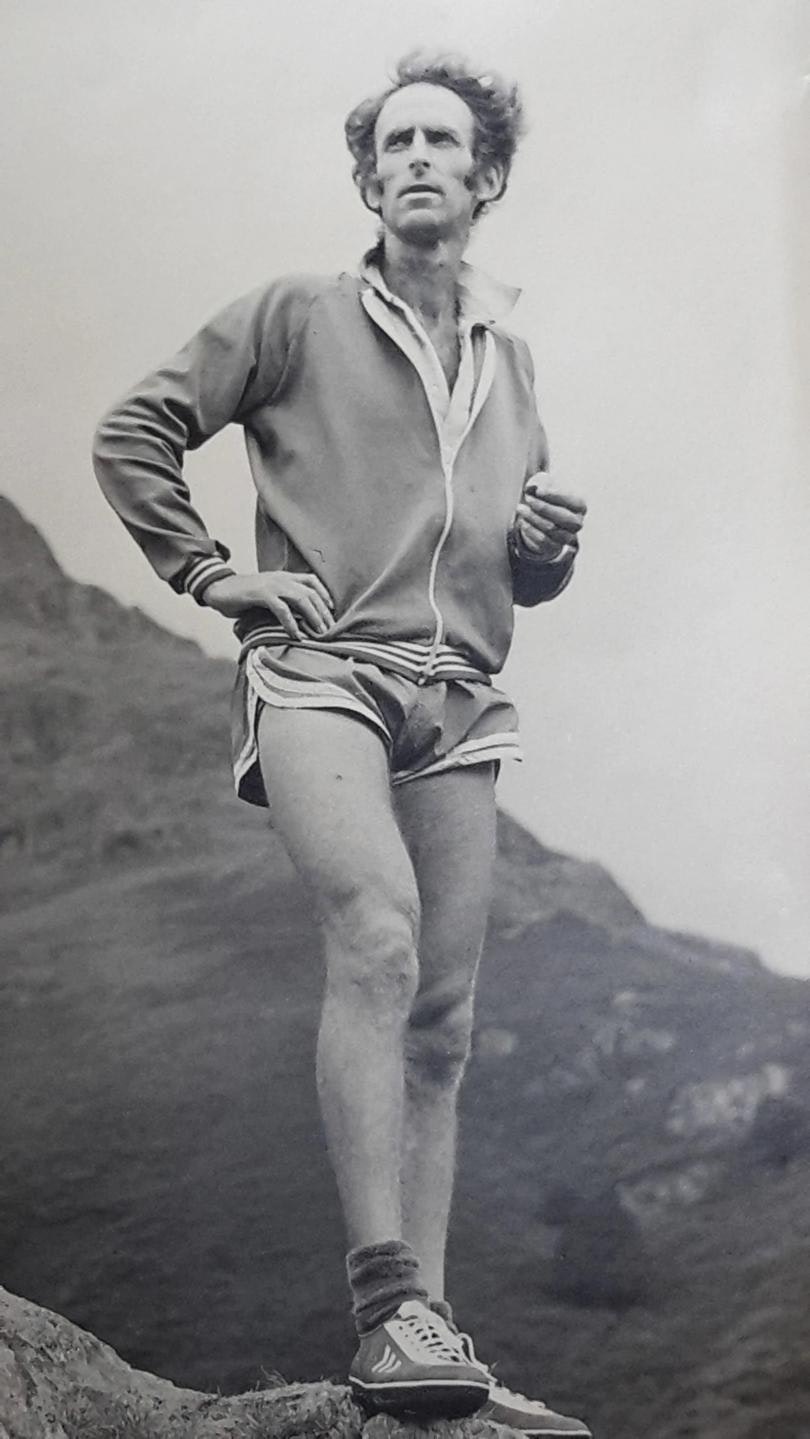

Then there’s Joss Naylor, a Wasdale hill farmer who did his first fell-running in work trousers cut off at the knee, fuelled himself with cake and Guinness and had a tendency to interrupt record attempts to attend to his sheep. His 1972 circuit of 63 peaks, completed in a raging storm, was described by the athlete-journalist Chris Brasher as “equal to any of the greatest Olympic races that I have ever seen”. This left little in the way of superlatives when, on a blisteringly hot day in 1975, Naylor, battling with cramp and dehydration (and a chronically bad back), raised the record to 72.

Naylor’s reputation was such that, when Jean Dawes became the first female record-holder in 1977, she refused his offer to pace her for fear that he would go too fast. But several who followed in her footsteps have rivalled Naylor for conspicuous indestructibility, notably the Yorkshire farmer Nicky Spinks, whose 65-peak record in 2021 seems almost tame compared with the double Bob Graham Round she did (in 45 hours 30 minutes) in 2016.

Such feats have little to do with the “marginal gains” of modern sports science. They’re about a determination that defies all reason in pursuit of an arbitrary goal. But that’s another strange thing that mountains do to us. We use them as the context for gratuitously difficult, self-imposed challenges — and then find ourselves forced to dig so deep in our efforts to accomplish them that we are transformed, for a while, into heroes.