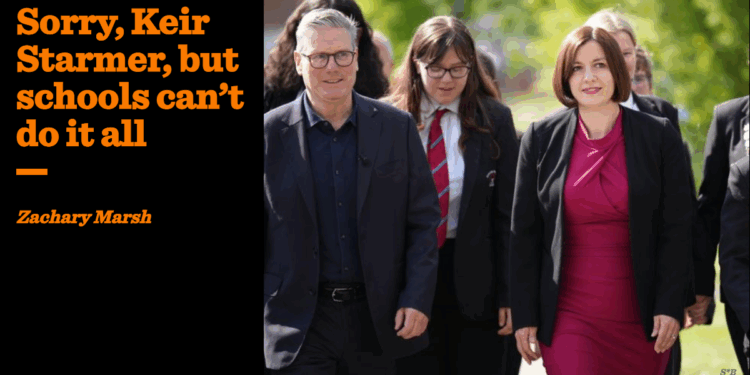

In his Labour conference speech, Keir Starmer took the welcome step of ditching his parties’ longstanding and disastrous target of 50 per cent of young people going to university. Yet in his laudable push to deliver better outcomes for young people through a wider range of destinations, he is planning to pile yet more pressure and obligations on schools that are not designed to meet them.

Subsequent details following Starmer’s speech set out a new responsibility for schools “in ensuring every pupil has a clear post-16 destination”. This proposal ignores the basic reality of how post-16 pathways work. Students face a myriad of options at the end of Year 11 — progression to sixth form, FE colleges, apprenticeships — for a dizzying array of courses. The vast majority of teachers and schools already do their upmost to support students — suggesting opportunities, supporting them with statement-writing and penning references. Yet ultimately, if a student refuses to make a serious attempt to secure a destination then a school is unable to compel them to.

This announcement is just the latest naïve move by government to place growing burdens and responsibilities on schools. Little by little, this is transforming education; turning institutions of learning into one-stop-shops for children’s services. Both Labour and the Conservatives have called for a mental health professional in every school. In the SEND system, investigations have found schools picking up the slack for healthcare treatments such as physical therapy in Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs). Most recently the Government announced a “national programme” of “supervised toothbrushing” for 3- to 5-year-olds in deprived communities in England.

All of these policies seek to deliver better outcomes for young people. Yet there is no reason why these things should be done by schools, which lack expertise and agency in many of these areas. As a result, they predictably often fail to deliver. As Policy Exchange’s report Out of Control highlights, a growing body of evidence highlights the poor effectiveness of universal schools-based mental health support. Shouldn’t such services be offered by specialists, in specialist settings, rather than being tacked onto the already crowded offer schools deliver?

The pernicious creep of this particular form of “everythingism” into education should not be easily dismissed. It is changing the very nature of what schools do and what it means to teach in them. We increasingly expect our teachers to double as social workers, placing a momentous workload strain on a struggling profession. In 2024 41,000 teachers quit the classroom. A detailed review by the Government in 2018 found workload was the number one factor contributing to teachers leaving.

A survey by the Department of Education last year found 75 per cent of teachers feel compelled to spend too much time on general admin, at the expense of their core roles of delivering great quality teaching. Just as worryingly, this shift is deterring a whole brand of recruits from entering the profession. It was once enough to love your subject and to wish to impart its substance and a passion for it to the next generation. Now, however, the social-work -ification of teaching is driving away those who rightly do not see these things as the role of educators.

Schools should be protected as institutions of teaching and learning with a clear, academic purpose

Every new unsuitable obligation thrust upon schools is just a further blow that leaves teachers feeling overwhelmed, disenchanted and powerless. Instead of adding to this burden, the Government should look to reverse the pressures that have been imposed. Responsibilities that do not match with what schools do should be placed elsewhere, with well-resourced and specialist services that can still provide the support young people need.

Schools should be protected as institutions of teaching and learning with a clear, academic purpose. Rather than evaluating teachers by the apprenticeships they wrangle for their students — or the whiteness of their teeth — they should be judged against the metrics they’ve trained for; the excellent teaching of their subject and progress students make in their classrooms.

Then we would be valuing teachers in the way that they deserve.