This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Roy Strong will be 90 on 23 August. Now living in Ledbury in Herefordshire, having sold The Laskett, the house and garden south of Hereford which he and his wife Julia Trevelyan Oman created, he remains remarkably intellectually active, having recently published a book on 17th century portraiture, still exercising furiously, keeping up with London artworld gossip. Although he comes to London less, he always seems to have seen all the latest exhibitions, including “Cecil Beaton’s Garden Party” at the Garden Museum before I did.

So, it is a good moment to look back and salute his importance as much more than just a museum director — he has been a writer, gardener, dandy, cultural commentator, diarist — over 50 years since he stood down as director of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) and moved to be director of the V&A.

It is easy to forget now that Roy Strong is best remembered as a museum director, responsible for exhibitions such as The Destruction of the Country House, 1875–1975 in the year he moved to the V&A, that his work as a flamboyant public figure was based on innovative scholarship. He is important as a writer on Tudor culture, bringing the study of Tudor portraiture into the mainstream, encouraging historians as well as art historians to think about how the monarchy used portraiture as a vehicle for propaganda.

This was because, unlike most museum directors, he had been a postgraduate at the Warburg Institute, not the Courtauld, writing his PhD on “Elizabethan Pageantry and Propaganda” under the intellectual historian Dame Frances Yates. His first scholarly publication, Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, was as drily academic a publication as it is possible to imagine.

Strong’s innovation at the NPG was a more theatrical system of presentation

In 1969, he published a two-volume scholarly catalogue of the Tudor and Jacobean portraits in the collection of the NPG, which he had worked on particularly during his first five years as a curator there (he was appointed as an assistant keeper with responsibility for the Tudor collection in September 1959) and he maintained his interest in Tudor portraiture long afterwards, doing an exhibition on Artists of the Tudor Court: The Portrait Miniature Rediscovered, 1520–1620 in 1983 when he was director of the V&A; and publishing The Elizabethan Image: An Introduction to English Portraiture, 1558–1603 as recently as 2021, demonstrating that he maintained a good scholarly knowledge of the subject long after he had ceased to be a conventional art historian.

His most important innovation at the NPG was the introduction of a more theatrical system of presentation both to temporary exhibitions and its permanent collection. The gallery’s top floor is nowadays unexpectedly more staid and straightforwardly focused on portraiture without any additional accoutrements than it was in the mid-1960s when Strong introduced close hanging of the pictures alongside photomontages and displays of weaponry to give a lively sense of mise-en-scène, turning it into more of a history museum than a shrine.

Strong was simultaneously responsible for a sequence of brilliantly theatrical exhibitions, beginning with The Winter Queen: Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia and Her Family which opened at the NPG in 1963. As he described it, he had the walls covered “with yards of buttered pleated muslin, persuading the carpenter to up-end old Victorian showcases, which we lined with wallpaper imitating watered silk, and arranged miniatures, books and other objects like a still life, ordering blow-ups of contemporary engravings which told the story of the Queen’s journey to the Palatinate”.

His exhibition of Cecil Beaton’s photographs, which opened at the end of October 1968, was designed by Richard (Dicky) Buckle, the balletomane. The images that survive of its installation look wild, with photographs pasted on the wall, an empty frame hung askew, and the biggest photos propped on a shelf so high that they must have been hard to see.

As Quentin Crewe wrote after it opened, “It is simply incredible that the trustees of such a fuddy-duddy organisation should pick a witty, zippy, mischievous man of thirty-two to look after the likenesses of the figures of British history.”

The following year, Strong was responsible for The Elizabethan Image at the Tate, designed by Christopher Firmstone. As Strong himself remembered the exhibition in the published version of his diaries, “Through the gloom of mid-Tudor iconoclasm, replete with the shattered images of saints, the visitor wended his way towards the shrine of Gloriana, in the midst of which stood a golden obelisk bearing her imagery, rainbows and spheres, sieves and crowned columns … It was unashamedly romantic but also highly disciplined, in exhibition terms a realisation of Sir Philip Sidney’s phrase, ‘the riches of knowledge upon the stream of delight’.”

The next thing for which Strong deserves to be remembered at the NPG is his pioneering role in promoting the serious study of photography not just as a medium of public record, but as an art form.

Not long after taking over as director in June 1967, he had lunch with Colin Ford, then at the British Film Institute, who suggested turning one of the galleries into a cinema. This led to the creation of a Department of Film, Photography and Television under Ford’s aegis in 1972, so that photographs are now at least as important as paintings to the way the NPG operates and collects, with a wide-ranging collection divided between its primary collection, where the acquisitions have to be approved by the Board of Trustees; and its archive collection which grew prodigiously under Ford’s successor, Terence Pepper.

It is hard now to reconstruct the impact that Roy Strong’s version of the National Portrait Gallery had on the world of museums. Instead of being dustily academic and run by the likes of Martin Davies, the excessively cerebral director of the National Gallery next door, Strong invented the idea of the museum as a popular, campaigning institution — not devoted to the entombment of the past, but to its reinvention.

Strong had a much harder time when he moved to South Kensington, not helped by the fact that, not long after he arrived, there were savage cuts which led to the closure of the still much-lamented Circulation Department (there was a proposal recently to reinstate it). The keepers of the departments into which the museum was divided regarded themselves as autonomous, looked down on him and did little to support him.

He opened The Destruction of the Country House exhibition before the end of his first year. It remains an exceptionally important and pioneering show, drawing attention to the many country houses which had been demolished since the Second World War because of high taxation rates. This led to a changed set of attitudes towards the imposition of a wealth tax by the incoming Labour government and a new approach to conservation, as revealed by the foundation of the conservation charity, SAVE, by Marcus Binney the following year.

From early on in his time as director, he was determined to get the museum to pay more attention to the 20th century, encouraging the departments to collect 20th century objects, establishing a shop run under the auspices of the Crafts Council and, if only briefly, encouraging makers into the museum.

Persuading the V&A departments to collect 20th century objects was not in the long term as significant as allowing the Conran Foundation to take space on a five-year lease in the basement of the old Boilerhouse Yard to house what was known as the Boilerhouse Project, run by the young Stephen Bayley, with a fast turnover of exhibitions on subjects like “Art and Industry” (the opening exhibition), “the Ford Sierra” and “Taste”. After five years, the lease was not extended, but it led to the creation of the Design Museum in Butler’s Wharf in 1988.

In 1980, Strong also started negotiations to establish a postgraduate course in the History of Design and the Decorative Arts jointly with the Royal College of Art. This was how I first met him. In November 1982, I was hired as a so-called assistant keeper to run the V&A’s side of the course, so was viewed, correctly, as his protégé.

Although I attracted the full odium of the Museum’s keepers as his appointee (at the adjacent table of my first lunch in the basement of Daquise, the keepers were plotting against their director), I always liked him: he was funny and irreverent; he got on well with the students; his instincts were correct that, in the long term, the existence of postgraduate teaching of design and decorative arts would improve the standards of scholarship in the subject.

To this day, I have never quite figured out what it was that triggered Strong to quit the V&A in February 1987, although the process of progressive disillusionment is clear in his diaries. At the time, it was thought that he did not see eye-to-eye with the chairman of the board of trustees, Peter Carington, the worldly ex-Foreign Secretary.

Even though Strong had himself been responsible for many of the people who had been appointed to the board of trustees when the V&A was made into a trustee museum in 1984, including Terence Conran, David Mellor and Jean Muir, they, and particularly Andrew Knight, gave him a hard time about how difficult it was to get anything done. Strong himself had found the same, but the trustees tended to blame him. He had been there 14 years, some of them very unhappy, stressed by the endless staff cuts, always sinking onto the floor of the car when driving past on his way to rural Herefordshire.

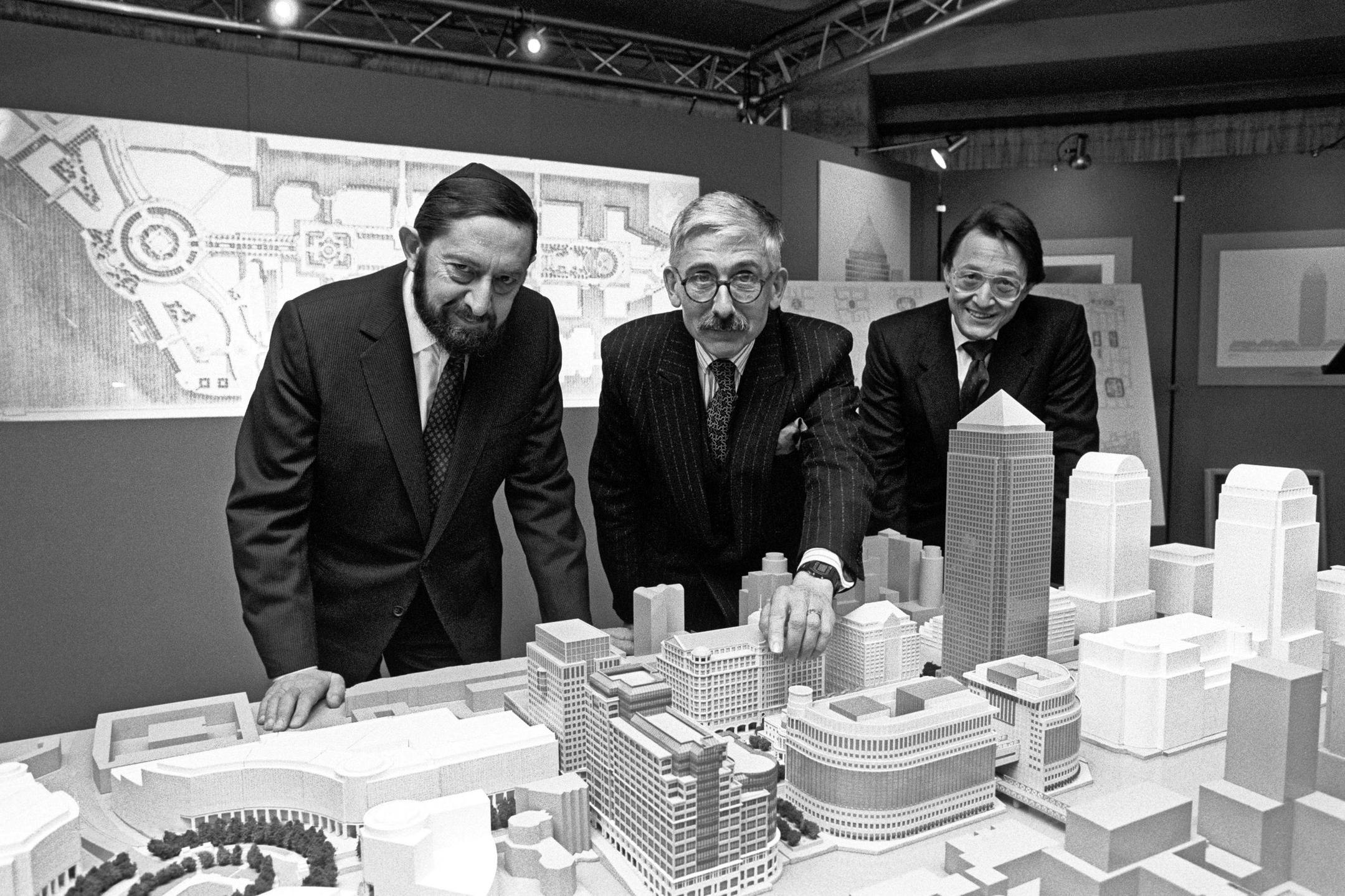

It helped that he was offered a job as an exceptionally well-paid adviser to Canary Wharf. He turned to writing books, which he had always done with great intellectual self-discipline, including publishing his diaries. He told the Guardian: “I look on life as an adventure and I am bored stiff. I shall now have the chance to write, be a professor in the United States, work on television, help to put through the Arts Council’s policy and be active on the South Bank Board.” In particular, it gave him more time to spend in Herefordshire and to travel, particularly to India where he led tours.

Now, as he turns 90, he is more benign than I have ever known him, less waspish, happy to reminisce about the days when he was courted by the grande dames of London society like Pamela Harlech. He keeps himself trim with a trainer and, as ever, looks in good shape, happy to show off his biceps and always beautifully dressed, if no longer able to afford Gianni Versace.

As we enter the dining room of the Garrick Club, eyes turn. He is a living national treasure.