This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

London’s “Frieze week” each October marks the most important time for many contemporary art galleries. The global art market focuses its attention on London for a few glamorous days. Frieze started in 2001 as a fair for contemporary art galleries in a large tent in Regents Park.

Since then, on the back of the enormous growth in appetite for contemporary art over the past three decades, it has added a second tent for exhibitors from more traditional areas of the art market, called Frieze Masters.

Not all contemporary art galleries today are struggling, but the costs of doing business in this previously booming sector are beginning to bite. Some galleries, even the larger, well-funded ones like Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, Pace, and David Zwirner, are scaling back their operations. In the US, several major galleries have decided to close, including Blum, Venus over Manhattan, and Clearing.

In the UK, things may not be quite as bad, but no one is saying it’s easy. Some galleries are even expanding, such as Ben Hunter, who took over the space at 44 Duke Street originally occupied by Jay Jopling’s White Cube (now in nearby Mason’s Yard).

White Cube was at the forefront of developing the international market for the Young British Artists (YBAs), with Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Mark Wallinger, Jake and Dinos Chapman at the head. The Sensation exhibition in 1997, often considered the starting point for the growth of the contemporary art market, was the touchpaper that brought the YBA market to a wider audience.

At the time, the leading British contemporary art galleries included Marlborough Fine Art, Karsten Schubert, Flowers, Lisson Gallery and the remarkable Anthony d’Offay.

Of these, d’Offay’s work was arguably the most intriguing, regardless of personal taste. He was a true original, seeking to present substantial works. Perhaps he was the last serious “gatekeeper” of the contemporary art market. Buying from d’Offay carried an air of seriousness and, importantly, validation.

D’Offay had worked with Warhol and Joseph Beuys, and I once met him to discuss the sale of a Victorian oak table, possibly designed by Pugin, which he had bought for his office from Christopher Gibbs. He never smiled: rather intimidatingly on the mantelpiece behind him was a small portrait of Beuys, by Warhol.

Despite his demeanour, I felt as if I was in the presence of a Faustian figure, someone capable of reshaping the trajectory of art history.

In 2001, d’Offay abruptly decided to retire. There was no explanation, no financial pressures; it was simply basta — ”enough”. Perhaps he foresaw the future? Did he envision a world where contemporary art was commodified, and its objects devalued?

Was the gallerist of the future working solely in the service of the buyer’s ultimate financial gain? Was the internet and the small screen transforming how art is sold, consumed, produced? Was the tail beginning to wag the dog?

Just a few years later works by young, so-called “wet paint” artists, such as Oscar Murillo, were sold from a gallery for a fairly modest price and then re-sold or “flipped”, like properties, months later at auction for a huge multiple of that original price, with little real explanation or evidence of a solid collector base seeking to buy those works — other than for profit.

Some artists’ primary market prices derived financial benefit from the huge secondary market increase in sales prices, but today, prices have come back down and the secondary market (for “wet paint” artists) is quiet again.

On the back of these unusually rapid price increases, the notorious fraudster Inigo Philbrick certainly exploited unwitting and often overly optimistic investors, as explained in the recent BBC two-part documentary The Great Art Fraud and in a book by his former friend Orlando Whitfield, All that Glitters: A Story of Friendship, Fraud & Fine Art. He won’t be the last.

There are signs of hope: most dealers working in the primary market (selling art from living artists) are serious about their practice, and work to find and promote talented artists they believe in.

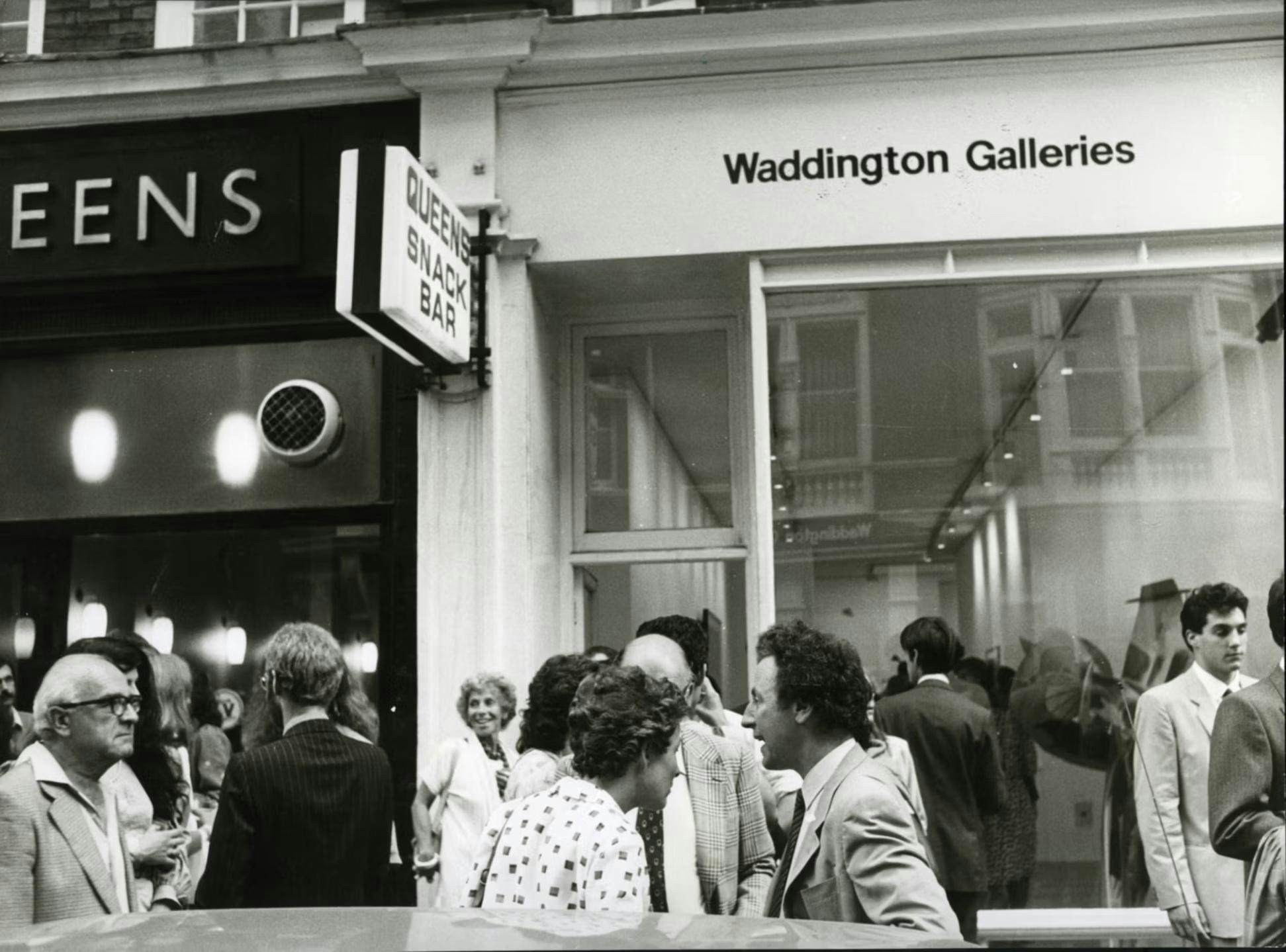

Cork Street — the post-war centre of gravity for London’s contemporary art scene, where Waddington has been located for years (in the 60s, far left) — is seeing a revival, with several major galleries taking space there in recent years, led by the Stephen Friedman gallery.

Hopefully, this year’s Frieze will mark a return to buying art for pleasure and quality, not just for what it might be worth in the future.