This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

When Richard Nixon coined the “war on drugs” in 1971, he was speaking metaphorically, assimilating the fight against illegal narcotics to armed conflict. We live in an age where nuance is regarded as an affectation, so it was not entirely surprising that Donald Trump should have taken the expression at face value.

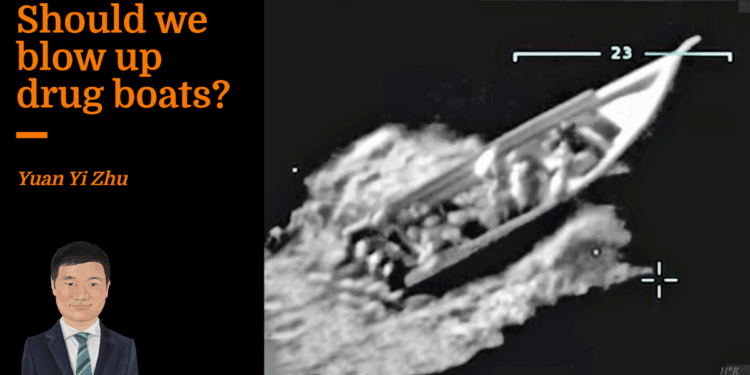

Since September, United States’ armed forces have been destroying from the air small vessels, which are allegedly used to transport drugs, in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific. As I write these words, almost 100 people have been killed in those strikes. The Trump administration has gleefully posted footage of these strikes for social media brownie points.

Unsurprisingly, the American left is enraged; but criticism has also emerged from less traditional quarters. John Yoo, the law professor who justified the Bush administration’s torture of terrorism suspects, and a man who cannot be accused of being a liberal bleeding heart, has all but called the strikes illegal. No serious lawyer, of whatever ideology, believes otherwise.

As Yoo points out, there is a difference between armed conflict and crime. Drug trafficking is bad; but it is a crime. Cartels want to make money, not to achieve conscious political objectives against state opponents, which is the main characteristic of a real war. Many things are bad, but that does not justify droning the people who commit them.

To put things in another perspective, your local weed dealer does not deserve to be blown up by flying robots with bombs on his corner. And if he gets nabbed, he cannot claim to be a prisoner of war nor claim the protections of the Geneva Conventions.

At this point, I pause to acknowledge that people in semi-submersible vehicles in the Caribbean are probably transporting drugs instead of looking for shipwrecks and are not thus the most sympathetic people (formerly) alive.

But one cannot exclude them from the criminal justice process by calling something a war, at least if one does not wish to worry unduly cancer patients and poor children.

Nonetheless, killing drug traffickers makes for good headlines, something which leaders from Brazil to the Philippines learned many years ago.

Moreover, having been elected on a promise to end foreign wars but (for reasons known to himself) keen to topple the detestable Venezuelan government, many suspect that the strikes are a pretext for Mr Trump to justify invading Venezuela, since the United States has long accused Nicolás Maduro of being involved in “narco-terrorism”.

Few countries are likely to want to burn their relations with the US president over this issue

There has been some backlash: reportedly, several NATO members have paused passing on intelligence to the United States in the region, worried about assisting an illegal endeavour through information-sharing.

Britain is said to have done so, although the government later denied such reports. Two American admirals are said to have had their careers curtailed because they had concerns about the strikes, although in neither case is this confirmed.

The strikes do have their fans. The prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, where charred bodies of unknown origin have been washing ashore, has expressed her approval. In this she is firmly within her country’s political traditions: one of her predecessors proposed the creation of an international tribunal dedicated to trying and hanging drug traffickers.

The result is the International Criminal Court, which does not try drug traffickers and does not execute anyone, but which does prosecute the likes of the former Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte for killing both drug traffickers and drug users (the ICC’s embattled British prosecutor claims that these actions amount to crimes against humanity; the trial has not begun).

Meanwhile, American liberals keen to invoke the magisterium of international law and of the rules-based international order must confront the awkward truth that Democrat presidents also engaged in similar extrajudicial killings, the difference being that they were engaged in the war on terror (arguably more “real” as a war) than the war on drugs.

How this will end is anyone’s guess. Cartels have excellent profit margins and are not likely to be deterred by losing a few disposable boats and (in their eyes) disposable crew. Few countries are likely to want to burn their relations with Trump over the issue.

Although some have suggested it as a possible outcome, the likelihood of American military personnel being prosecuted for participating in the strikes is basically nil. Contrary to popular belief, “I was only following orders” is in fact a valid defence in international criminal law, at least in some circumstances.

But those who cheer the strikes should remember that there are very good reasons why all civilised peoples draw a distinction between the prosecution of ordinary crimes and war, even when it is satisfying to watch clips of extrajudicial killings online.