Our alternative is much more popular than Christ’s College’s new proposed library

Should new buildings in Cambridge make the town better or worse? Should they be joyful or joyless, symbolic or meaningless? Does it matter if people like them or not? Should the planning system care? Does the “spirit of the place” matter more or the “spirit of the age”? Are we building for a self-regarding, isolated elite, ignorant of and contemptuous of public opinion, or for the passing man and woman?

To judge by Christ’s College’s new proposed library which the fellows have recently submitted for planning and which the City of Cambridge has recently approved the answers are: “worse”, “joyless”, “meaningless”, “no”, “it should not care”, “the spirit of the age” and “a self-regarding elite”. And to judge by our national public opinion poll, the public don’t like it.

Something is either very wrong with the people or with the way we design and build.

For hundreds of years every building in our two ancient universities was built with a rich array of visual patterns from the most modest detail to the sweep of the entire edifice: lanterns and lancet windows, domes and dentils, mullions and modillions. These patterns were constantly being re-used, re-purposed, emulated and evolved. If no collegiate building was entirely original, nor could any building be a perfect simulacrum, even when it supposedly set out to be. Both Oxford and Cambridge have a so-called Bridge of Sighs. But neither would fool a Venetian.

Literally every single collegiate building in our two most ancient English universities created before the mid-twentieth century made use of patterns which were well known but which adapted them to the brief. To do otherwise would have struck the colleges’ fellows and their architects as perverse. Nicholas Hawksmoor’s eighteenth-century library at All Souls Oxford, for example, has gothic windows and finials on the outside but a Jacobean ceiling and baroque balustrade on the inside.

At Christ’s College itself, the original fifteenth and sixteenth century buildings deployed gothic arches and windows whose forms were centuries old, just as the subsequent Stevenson, Blyth and Memorial buildings in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries deployed classical forms which were millennia old. None, however, would convince anyone as being early medieval or truly antique. They are palpably Tudor, Victorian and Neo-Georgian. Traditions live and evolve and repeat and rhyme.

Or at least they did, until the great mid-twentieth century rupture when architects and public bodies became fixated with an unforgiving belief that new buildings must speak only of their age rather than of their place. Innovation became prized over all criteria of civility, comfort and comeliness. The result has been roofs that leak, sustainable buildings that don’t endure, student lodgings that undergraduates seek to avoid and buildings on streets that turn their posteriors to the public realm.

For 80 years, Oxbridge has been particularly guilty of some of the worst public architecture in Britain, irresilient and feckless. Such a building, for example, was Christ’s New Court by Denis Lasdun. Known as the “typewriter”, 25 years ago it was widely disliked by undergraduates. I have no idea if it still is or not, but even modernist apologists concede that it is “controversial” (normally a weasel word for being widely detested) while one added primly that it “had big trouble relating to the street.” That is true. I would add that it has big trouble relating to the college.

Other the last generation, more Oxbridge colleges are thankfully realising their error. After a 50 years’ lacuna they are again commissioning buildings which nestle more comfortably in their settings. Happy examples abound. The Levine Building at Trinity, Oxford by Hugh Petter; Ann’s Court and the Bartlam Library at Selwyn College, Cambridge by Demetri Porphyrios; the New Entrance Quod at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford and the Whittle Building at Peterhouse, Cambridge both by John Simpson are notable examples.

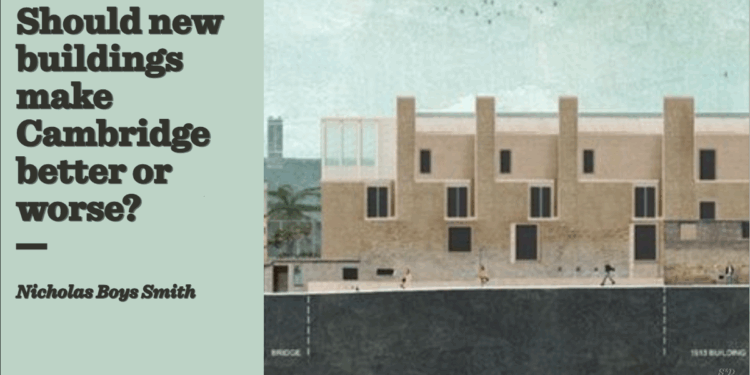

Sadly, however, the new library at Christ’s College will not join their ranks. Eager to repeat the error of Lasdun’s typewriter, the fellows of Christ’s have recently commissioned a new library which, if it can do nothing else, might win first prize in the competition for the blankest, blandest and most boring collegiate building created in our lifetimes: a blank wall without ornament or pattern, a blank array of windows without sills or architrave, blank chimneys without crown or neck or pattern. The lowest windowsills are head height. There are no doors, no love, no detail, no joy. Blankness everywhere: up, down, left and right. Blankness cubed. This is a building, at best to ignore and, at worst, to make you sad.

It is also a greedy building. As well as being contemptuously ugly to narrow Christ’s Lane along which it runs, it is also too high for the space. It greedily gobbles up light and sky creating a canyon effect alongside the building opposite. The height of the building (over 14m) along a 6m wide lane creates an enclosure ratio of over 2:1 which is higher than Create Streets would normally advise.

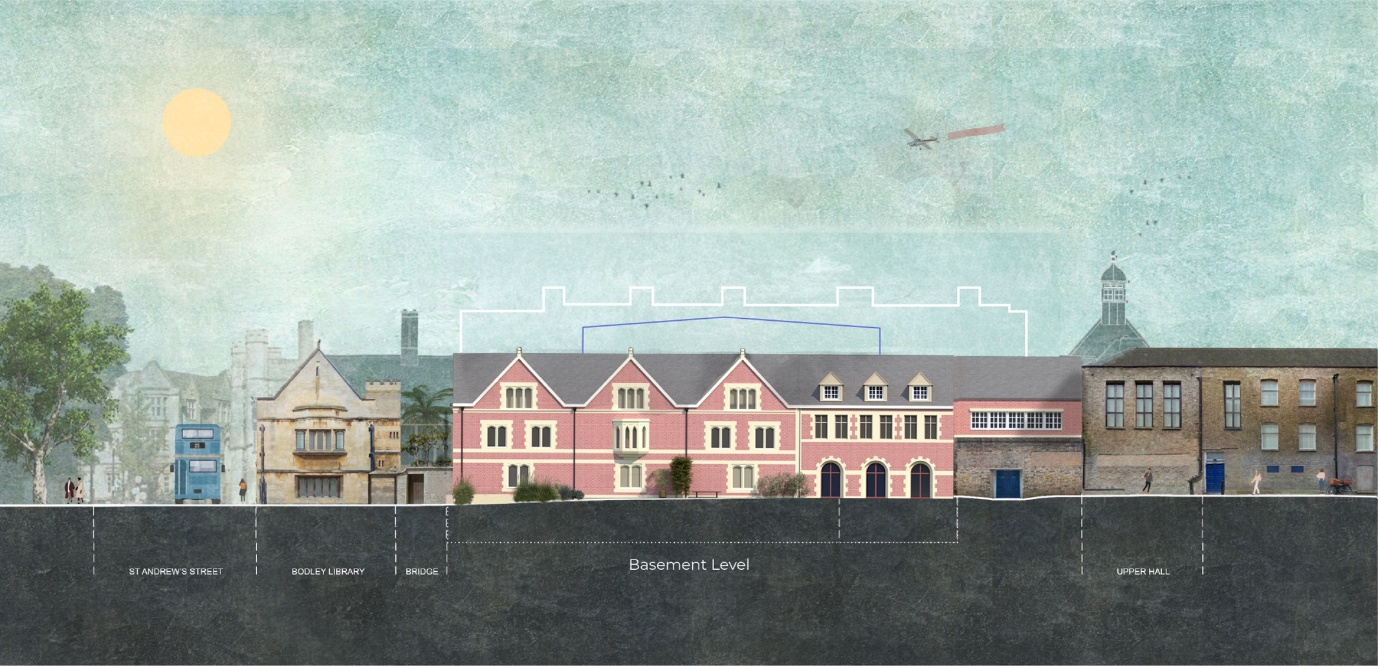

Disgruntled neighbours therefore commissioned Create Streets to create an alternative design which better reflects what the public tends to like and then ask the public what they prefer. We gave ourselves three main criteria: reducing the height by making better use of the basement, creating a more active and joyful face and being more respectful of the neighbouring Bodley Library.

We then submitted the two design proposals to the polling firm, Deltapoll, to find out which building the public preferred. Both images were identical street views looking northeast along Christ’s Lane, except for the change of building. Respondents were also shown the corresponding elevations alongside the street. A “don’t know” option was provided. For each group, respondents were asked a deliberately neutral question:

“A new university college library building has been proposed in Cambridge. Assuming all other things being equal, which ONE of these options do you yourself prefer?”

A representative sample of the British public overwhelmingly preferred the alternative design to Christ’s College’s proposals: 71 per cent chose our alternative design as their preferred building. Just 21 per cent opted for Christ’s College’s proposal. 8 per cent did not know.

This view is highly consistent across all gender, age, income and voting demographics. Strong majorities of all segments preferred the alternative design. In an age of division, here is something that brings us together.

Men and women agreed. Both genders equally preferred the alternative design by some margin, with 72 per cent of men and 72 per cent of women choosing it.

The two images that were shown to respondents in the Deltapoll survey. The alternative design was much more popular than Christ’s proposals.

People of different social grades and income completely agree. There was only a few per centage points difference between different social grades (ABC1 and C2DE) and across income level.

All age groups preferred our alternative design. It was most popular with the young. 79 per cent of those aged 18 — 24 preferred our plans (with 18 per cent preferring Christ’s College’s plans) which was higher than all other groups.

The alternative design was marginally more popular with Liberal Democrat voters as opposed to other political parties, and equally popular across Conservative and Labour voters. 77 per cent of Liberal Democrat voters preferred the more humane design. Conservative and Labour voters held almost identical preferences for it, of 68 and 69 per cent respectively.

This is not the first time Create Streets has tested public visual preferences in this way. And every poll we have ever conducted tells the same story, as they also do in the US. What people like is easy to predict. So much so that, as our recent research with Professor Nikos Salingaros was able to show, large language models can accurately anticipate human preferences if you ask it questions such as “which building will people find more friendly.”

None of this means that every new building must strictly imitate the past. But it does mean that we should learn from what the public consistently value: proportion, enclosure, variety, material richness and human-scale rhythm. Those principles are not “classical styles”, they are courtesy to the street, to those who pass by and to our common home and civic life.

The college should be ashamed that they commissioned this building which is as unpopular as it is bland and uncivil. The architects should be ashamed that they designed it. And the local council should be ashamed that they approved it. They all could and should have done better. This is a failure of stewardship, courtesy and love.

I dream that one day planners, architects and developers will rediscover the humility not to patronise their fellow citizens but to actually respect what they say. The evidence for public preferences is building and building. How long can investors, developers, planners and architects keep ignoring it?