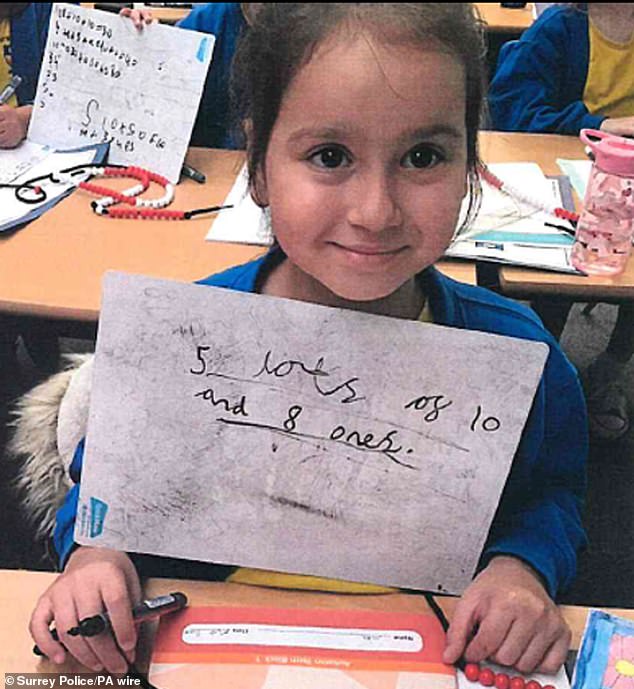

She was ‘a beautiful little girl with a lovely smile and a loud laugh’, but ten-year-old Sara Sharif never stood a chance.

Her sadistic father Urfan, 43, and stepmother Beinash Batool, 30, beat her to death while the authorities stood by worrying about matters like racial sensitivity and data protection.

Here, Rebecca Camber examines the catalogue of blunders and missed opportunities that sealed her fate.

DOMESTIC ABUSE PERPETRATOR HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

A harrowing safeguarding review on Thursday revealed how Sara’s father was well-known for violence against women and children years before she was born.

Urfan Sharif had been reported to police and social services after being accused of attacking three women and two children, including a one-month-old baby.

After arriving in the UK on a student visa, the Pakistani taxi driver held one woman at knifepoint, choked another with a belt and imprisoned one girlfriend for five days while he sent her passport off for a marriage application in a bid to secure residency in the UK.

But he was never charged with any offence after shifting the blame on to his victims each time.

Sara Sharif was described as ‘a beautiful little girl with a lovely smile and a loud laugh’

A report into the 10-year-old’s death has revealed a number of failings

Social services were called repeatedly after Sharif was accused of biting, hitting, burning, pinching and slapping children, but no further action was taken after he blamed Sara’s mother Olga Domin.

Sara was taken into foster care in 2014 at the age of two, but despite the local authority believing she should be adopted, only a 12-month supervision order was put in place ‘without adequate safeguards’.

Meanwhile, her father spent his time drinking and gambling, eventually leaving Ms Domin to fly to Jhelum in Pakistan where he secretly married his cousin in an Islamic ceremony before he returned to embark on a third marriage with Beinash Batool.

In 2016 Sharif was ordered to go on a domestic violence perpetrator programme after Ms Domin accused him of hitting her and children.

Sharif ‘admitted to extensive and wide-ranging domestic abuse’, but only attended eight out of the 26 sessions and experts said there was ‘not enough evidence’ that he had changed his behaviour.

Despite the report on his attendance at the domestic violence perpetrator programme making ‘quite shocking reading’, its significance ‘became lost within the system’ when a social worker failed to complete an analysis and it was not added to Sara’s safeguarding report.

HOODWINKING THE AUTHORITIES

At Easter 2019, during a visit to Sharif’s home, Sara suddenly started accusing her mother of violence, claiming she tried to drown her in the bath and burn her with a lighter.

Sara was taken into foster care in 2014 at the age of two, but despite the local authority believing she should be adopted, only a 12-month supervision order was put in place ‘without adequate safeguards’

Under pressure from Sharif, Sara made spurious reports that her mother had slapped her, pinched her and pulled her hair.

Sharif took Sara to a walk-in centre claiming she had been attacked by Ms Domin, but doctors failed to investigate who was really responsible.

The father recorded the allegations in a video, but no one thought to question whether the man behind the lens might be the real perpetrator.

THE ‘PIVOTAL’ CUSTODY BATTLE

Despite the slew of allegations against Sharif, social workers recommended that Sara should move back into her father’s ‘safe and loving home’.

In October 2019, a judge at Guildford family court ordered that Sara live with Sharif and her new stepmother Batool.

The judge was persuaded by a flawed report which had critical gaps in information about Sharif because an inexperienced social worker was under pressure to file it on time.

Sara’s Polish mother was made out to be ‘the problem’ and her ‘voice became lost’ because there was no court interpreter to explain what was happening, leaving her ‘marginalised’ and ‘cut off’ from decisions about Sara’s fate.

Murderers: Sara’s violent father Urfan Sharif, 43, and her stepmother Beinash Batool, 30

The safeguarding review described the judge’s decision as ‘pivotal’, adding: ‘A great deal of information, especially about the risks posed to her by the father was available across the system but opportunities were lost to join up all the dots and recognise the dangers faced by Sara once she moved in with her father and stepmother.’

Consequently, ‘red flags’ were missed as there was an ‘assumption that because the court had decided that Sara could live with him there was no need to be unduly concerned’.

COVID LOCKDOWN

During the Covid lockdown, Sara ‘effectively disappeared from view’ when her father and stepmother began doling out daily beatings.

She was offered a school place, but Sharif chose to keep her at home to hide her injuries.

When she returned in September 2020 teachers noted that ‘past trauma and a hectic home life’ was affecting Sara’s behaviour.

THE HIJAB

By 2021, Sara’s demeanour had changed and she started wearing a hijab to hide the bruises, which was not questioned by social workers even though none of her family wore one.

By 2021, Sara’s demeanour had changed and she started wearing a hijab to hide the bruises, which was not questioned by social workers even though none of her family wore one

Experts told the review it would be highly unusual for a young child to wear one in the circumstances, but teachers accepted Sara’s excuses that she wanted to emulate her father’s Pakistani heritage.

The review found professionals failed to consider Sara’s ‘race, culture, religion or heritage’ including why a Pakistani father chose to pick on his dual-heritage daughter.

Teachers noticed Sara’s bruises in June 2022, but the scared pupil would pull down her hijab and brush off injuries as accidental.

An occupational therapist sent to the home noted Sara was the only person wearing a hijab but didn’t think this was unreasonable, ‘although she has reflected that she may have been reticent to talk about it for fear of causing offence’.

HOME SCHOOLING

When teachers raised questions about Sara’s bruises in 2022, Sharif quickly announced she would be home-schooled.

Her school had no idea of Sharif’s history because it was not in their files. Sara later returned to school, but in March 2023 she went off sick before returning to lessons with three facial bruises, including a golf ball size injury to her cheek.

The headteacher called social services but Sharif blamed another child and claimed Sara had injuries from birth.

Teachers believed they could ‘get in trouble’ for sharing information due to data protection concerns, which meant Sharif’s lies about another child being responsible were not disproved.

After ‘superficial analysis’, the case was closed with no further action just six days later without any police inquiries.

THE WRONG ADDRESS

Sara was withdrawn from class to be home-schooled on April 17, 2023 and was never seen alive outside the home again.

A home education visit was supposed to take place within ten days but was delayed due to staff sickness and annual leave.

When the team did visit, they got the wrong address on August 7. Within 24 hours, Sharif had fatally beaten Sara with a pole causing her death on August 8.

‘If Sara had been seen, it is likely that the abuse would have come to light,’ the report concluded.

‘There were numerous times before Sara was born and throughout her life, that the seriousness and significance of [her] father as a serial perpetrator of domestic abuse was overlooked, not acted on and underestimated by almost all professionals who became involved with Sara and her family.

‘The review reveals many points at which different action could, and we suggest, should, have been taken.

‘It is this accumulation of many decisions and actions over time that contributed to a situation where Sara was not protected from abuse and torture at the hands of her father, stepmother and uncle.’