The message on the smartly embossed card was so matter-of-fact that its true significance would have remained hidden to all but the most seasoned royal watcher.

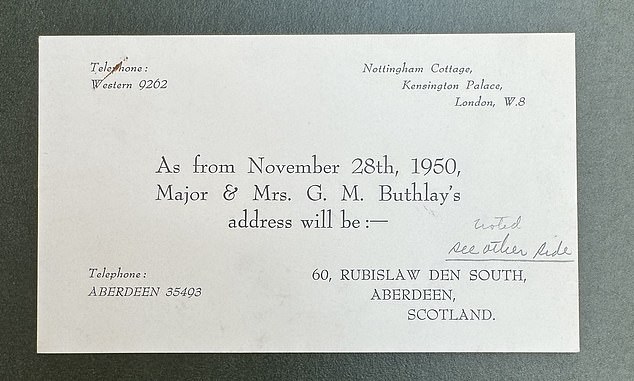

‘As from November 28th, 1950,’ it read, ‘Major & Mrs GM Buthlay’s address will be 60 Rubislaw Den South, Aberdeen, Scotland.’

It was where the Buthlays had moved from, however, that really caught the eye – Nottingham Cottage, Kensington Palace, London W8.

This two-bedroom grace and favour residence in the grounds of the royal estate had been gifted to Mrs Marion Buthlay for her lifetime in gratitude for her unstinting and inspirational service raising two princesses of the realm.

Better known by her maiden name, Marion Crawford was the former royal governess who had been affectionately known by her charges – the late Queen Elizabeth II and her sister Margaret – as ‘Crawfie’.

For 17 years, Crawfie occupied a unique position in their lives, taking on the role of playmate, confidante and constant companion.

She guided them through the trauma of the abdication of their uncle, their father’s accession to the throne and the terrors of the Second World War – even hunkering down with them in the Windsor Castle dungeons as Luftwaffe bombers roared overhead.

And yet, as the wording on that simple change of address card starkly reveals, Crawfie and her husband were forced to flee London just a year after retiring from royal duty, hounded out after making the ill-fated, if lucrative, decision to write a memoir recounting her time with the Royal Family.

‘Crawfie’ with young Princess Elizabeth before she was cast out from royal circles

The house in Aberdeen where Crawfie retreated after the Royal Family turned their back on her

Her closeness to the House of Windsor was to collapse dramatically following the publication of her book The Little Princesses in 1950.

The Royal Family considered it an act of treachery and Crawfie and her adventurous new husband, Major George Buthlay, an ex-soldier and banker, were kicked out of Nottingham Cottage.

They escaped to Aberdeen where they purchased 60 Rubislaw Den South. Her new home, which has just gone on the market again at offers over £1.5million, lies in one of the country’s smartest postcodes, but for a heartbroken Crawfie it felt forever like a place of exile.

From a humble start as the daughter of a clerk and a seamstress, she left Dunfermline High School in Fife and went to train as a teacher at Edinburgh’s Moray House.

A star student, she adopted progressive ideas about the whole child and believed in the importance not just of learning from books, but of giving children opportunities to get outdoors and take exercise.

She was only 22 when she was hand-picked by the then Duke and Duchess of York, to oversee the education of their two young daughters.

Such was the influence she exerted, and her standing with the Royal Family, that she even persuaded the King to let the princesses taste something of ‘ordinary’ life by allowing them to ride with her on the London Underground, to play in Hyde Park and to take swimming lessons at a nearby public pool.

And it was to her governess that the future Queen Elizabeth II rushed with news of her blossoming feelings for the young Prince Philip of Greece.

The fact she had been privy to such intimate aspects of royal life gave her a unique position when it came to writing her divisive book.

First published as a series of articles in US magazine Ladies’ Home Journal (LHJ) and Woman’s Own in the UK, it netted the former governess $85,000 – worth more than a million dollars in today’s money.

By modern standards her revelations were tame, affectionate, even sycophantic.

She described Princess Elizabeth tipping a pot of ink over her own head in a rare moment of schoolroom rebellion, and the two princesses mischievously pinching their dog to get it to bark down a transatlantic phoneline to their parents who were in America, together with high-spirited family pillow fights.

But the fact she had spoken at all infuriated the Palace who said she had no business sharing private family stories without the permission of her former employers.

From that moment on she was cast out into the cold.

Though Palace officials portrayed the falling out as the result of a betrayal of confidences by the governess, the deal had been brokered with the Palace by the Foreign Office, who believed that a series of articles about the royal family in a US magazine would boost Anglo-American relations.

And far from being oblivious to the scheme, the Queen Mother and Princess Elizabeth had met the American magazine editor Beatrice Blackmar Gould several years earlier to discuss the possibility of collaborating on a series about royal life.

Eventually it was agreed that, instead of granting an interview with the future Queen herself, a member of the Palace staff who knew her well would be interviewed by a journalist for the articles.

In a letter to Crawford from this time, the Queen Mother referred to a Times journalist, Dermot Morrah, whom the Palace had proposed as a suitable person to write the articles based on interviews with Crawford.

The Queen Mother wrote to her: ‘Mr Morrah, who I saw the other day, seemed to think that you could help him with his articles and get paid from America. This would be quite all right as long as your name did not come into it.’

The Queen Mother’s objection arose late in the day when she learned that Gould had persuaded Crawford to let them use her by-line, arguing that nobody but her could have provided such an intimate account of life inside the sisters’ schoolroom.

Fifteen million people read her story. The response was overwhelmingly positive. On the back of it, Crawford was offered a regular column in Woman’s Own writing on royal matters, and there was talk of The Little Princesses being turned into a Rogers and Hammerstein musical.

But while the tale was a hit around the world, ‘doing a Crawfie’ became shorthand within royal circles for the ultimate act of betrayal.

The Queen Mother forbade the princesses and Palace staff from ever talking to her again. Aides were instructed that if the former governess ever wrote to anyone in the Palace, they were to throw her correspondence in the fire.

By contrast, the editors of the LHJ were invited to take tea at the Palace to celebrate the public relations triumph.

In Aberdeen, Crawford could not forget ‘the girls’. Under her bed she kept a box of their childhood drawings along with the Christmas and birthday cards they had sent her over two decades.

A wedding photo of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip was given pride of place on the mantlepiece in the sitting room, next to a photo of the Buthlays’ own wedding.

The two wedding ceremonies, one conducted in the full glare of the world’s media, the other a private affair described in one newspaper as ‘one of the quietest ever held’ at Dunfermline Abbey, had taken place within months of each other, in 1947.

Even after Crawford married Buthlay, the Queen Mother had insisted that she return to London to work with their youngest daughter for two more years until her studies were completed.

Crawford was 40 years old by the time Princess Margaret finally graduated from her schoolroom in 1949 and she was discharged from royal duty.

The many sacrifices Crawford made to serve them – not least delaying her own marriage by eight years – seemed not to register with her employers.

The governess and her husband never had children of their own, making the nine bedrooms of their Aberdeen home a luxury rather than a necessity.

Built for entertaining, the couple threw lavish dinner parties there. George, ebullient and gregarious, loved being the centre of attention, while Crawfie, who was tall and lean with a severe short haircut, never lost the prim air of the schoolmistress she had once been.

A card announcing the Queen’s former confidante’s move

The couple had hampers of food and wine sent up by train from Fortnum & Mason in London, suppliers to the royal household.

Within a month of moving in, though, Crawford was confessing to friends: ‘I find the house much too large, but I love Aberdeen and the surrounding country, and after we get settled, I look forward to many years of peace and happiness here.’

The house has undergone extensive renovation and modernisation in the years since the couple lived in it, but it retains many original period features including ornate cornicing and stained glass. A glass panel above the front door is decorated with a lion and carries the Latin inscription ‘Fortiter cerit crucem’ meaning ‘he bravely carries the cross’.

In later years, the Buthlays moved to a more modest house overlooking Aberdeen’s North Deeside Road – the very road the Royal Family passed along on their way to and from Balmoral Castle, their beloved holiday home. Crawford told a close friend she had written to her former employers begging for a truce, but no one ever replied.

Depressed in her final years, she attempted suicide twice. Her friends blamed the Royal Family. ‘It was clear she was asked by the Palace to do the articles. Then they made an example of her and cast her aside. Crawfie was devastated and completely heartbroken by what they did to her,’ said her close friend Nigel Astell.

Though only 50 miles from the gates of Balmoral, No 60 symbolises the unbridgeable rift between the Royal Family and one of their most loyal servants.

Neighbours remember her as a widow sitting by the fire looking through her box of mementos, her life marred by rejection and regret.

When she moved into a nursing home in her twilight years, she took these souvenirs with her. It contained several hand-made Christmas cards lovingly inscribed from Elizabeth and Margaret to the tutor they adored, along with some more formal greetings cards.

Its place among her possessions in the home showed how fondly she still looked back on that time and gave an indication of the enduring heartbreak she must have suffered over the loss of that bond.

When she died a lonely widow of 78, neither the Queen, the Queen Mother nor Princess Margaret sent a wreath or a card to her funeral.

The publication of her novel may have brought her a handsome fee, but it was clear she paid a far higher emotional cost.