It has baffled scientists since it was first discovered back in 2018.

But the mystery of the ‘Dragon Man’ skull and its true identity has finally been solved, a new study reveals.

Using DNA samples from plaque on the fossil’s teeth, researchers have proven that the Dragon Man belonged to a lost group of ancient humans called the Denisovans.

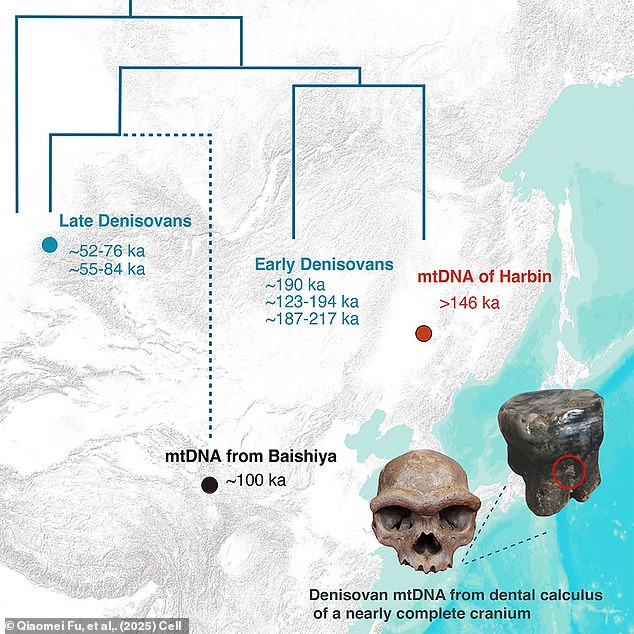

This species emerged around 217,000 years ago and passed on traces of DNA to modern humans before being lost to time.

Denisovans were first discovered in 2010 when palaeontologists found a single finger of a girl who lived 66,000 years ago in the Denisova Cave in Siberia.

But with only tiny fragments of bones to work with, palaeontologists couldn’t learn anything more about our long-lost ancestors.

Now, as the first confirmed Denisovan skull, the Dragon Man can provide scientists with an idead of what these ancient humans might have looked like.

Although not directly involved in the study, Dr Bence Viola – a paleoanthropologist at the University of Toronto – told MailOnline: ‘This is very exciting. Since their discovery in 2010, we knew that there was this other group of humans out there that our ancestors interacted with, but we had no idea how they looked except for some of their teeth.’

Scientists have finally solved the mystery of the ‘Dragon Man’ skull which belonged to an ancient human who lived 146,000 years ago

Scientists have now confirmed that the skull is that of a Denisovan (artist’s impression), an ancient species of human which emerged around 217,000 years ago

The Dragon Man skull is believed to have been found by a Chinese railway worker in 1933 while the country was under Japanese occupation.

Not knowing what the fossilised skull could be but suspecting it might be important, the labourer hid the skull at the bottom of the well near Harbin City.

He only revealed its location shortly before his death, and his surviving family found it in 2018 and donated it to the Hebei GEO University.

Scientists dubbed the skull ‘Homo Longi’ or ‘Dragon Man’ after the Heilongjiang near where it was found, which translates to black dragon river.

The researchers knew that this skull didn’t belong to either homo sapiens or Neanderthals but couldn’t prove which other species it might be part of.

In two papers, published in Cell and Science, researchers have now managed to gather enough DNA evidence to prove that Dragon Man was a Denisovan.

Lead researcher Dr Qiaomei Fu, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, had previously tried to extract DNA from bones in the skull but had not been successful.

To find DNA, Dr Fu had to take tiny samples of the plaque that had built up on Dragon Man’s teeth.

The Dragon Man skull was discovered by a Chinese labourer near Harbin City in 1933 but remained hidden in a well until 2018. Scientists knew that it was not a Neanderthal or Homo Sapiens skull but could not prove which species it was until now

Scientists extracted DNA from the plaque on one of Dragon Man’s teeth which contained traces of cells from inside his mouth. This DNA matched samples taken from Denisovan bones

Previously, the only traces of Denisovans were small fragments of bone like these pieces found in Siberia which meant scientists didn’t know what they might have looked like

As plaque builds up it sometimes traps cells from the inside of the mouth, and so there could be traces of DNA left even after 146,000 years.

When Dr Fu and her colleagues did manage to extract human DNA from the plaque, it was a match for samples of DNA taken from Denisovan fossils.

For the first time, scientists now have a confirmed Denisovan skull which means they can work out what our lost ancestors actually looked like.

The Dragon Man’s skull has large eye sockets, a heavy brow and an exceptionally large and thick cranium.

Scientists believe that Dragon Man, and therefore Denisovans, would have had a brain about seven per cent larger than a modern human.

Reconstructions based on the skull show a face with heavy, flat cheeks, a wide mouth, and a large nose.

However, the biggest implication of the Dragon Man skull’s identification is that we now know Denisovans might have been much larger than modern humans.

Dr Viola says: ‘It emphasizes what we assumed from the teeth, that these are very large and robust people.

Now scientists have a confirmed Denisovan skull, they can predict what they might have looked like. This suggests that Denisovans would have been strong, heavily-set hunter-gatherers with heavy brows and large brains

This also confirms that Dragon Man was from an older lineage of Denisovans which dates back to the earliest records around 217,000 years ago, rather than from the late Denisovan line which branched off around 50,000 years ago

‘Harbin [the Dragon Man skull] is one of, if not the largest human cranium we have anywhere in the fossil record.’

However, scientists still have many questions about Denisovans that are yet to be answered.

In particular, scientists don’t yet know whether Dragon Man reflects the full range of diversity that could have existed within the Denisovan population.

Dragon Man was probably a heavily-set, stocky hunter-gatherer built to survive the last Ice Age in northern China but Denisovan bones have been found in environments that weren’t nearly as cold.

Professor John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, told MailOnline: ‘Harbin gives us a strong indication that some of them are large, with large skulls.

‘But we have some good reasons to suspect that Denisovans lived across quite a wide geographic range, from Siberia into Indonesia, and they may have been in many different environmental settings.

‘I wouldn’t be surprised if they are as variable in body size and shape as people living across the same range of geographies today.’