In November 1988, a 17-year-old schoolgirl named Junko Furuta left work and pedalled home on her bike, like thousands of other students in the suburbs of Tokyo. But she never made it back.

In the months that followed, details of what happened to her would leak out in fits and starts before exploding into one of the most widely discussed and reviled criminal cases in modern Japanese memory – often described by commentators as the ‘Concrete-encased High School Murder’ for the grisly way her body was eventually discovered.

Over the span of 41 days, the high school student was abducted by four teenage boys aged between 16 and 18, subjected to unimaginable abuse, repeatedly raped, and ultimately murdered.

The boys, one of whom was said to be a low-ranking member of the infamous Japanese Yakuza gang, carried out brutal acts, including inserting objects into her genital area, setting her on fire, forcing her to drink her own urine, and eat live cockroaches.

The case would not only destroy a family, but it would ignite a national debate about juvenile punishment, media secrecy, and how a modern society should respond when its children commit the most monstrous of crimes.

Junko Furuta was born in January 1971 and grew up in Misato, Saitama Prefecture. Friends and teachers described her as a bright, hard-working pupil with ordinary teenage dreams.

But on the evening of November 25, 1988, she was attacked while making her way home from her part-time job.

Hiroshi Miyano, 18, and Shinji Minato, 16, had been riding around the neighbourhood on their motorcycles with the intention of robbing and raping local women when they spotted Furuta.

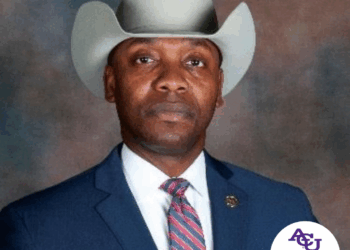

Junko Furuta, 17, was gang-raped, tortured and murdered by four young men in Japan in 1988

Shinji Minato agreed to allow Furuta to be confined in a room on the second floor of his house in Adachi so they could continue to gang-rape her

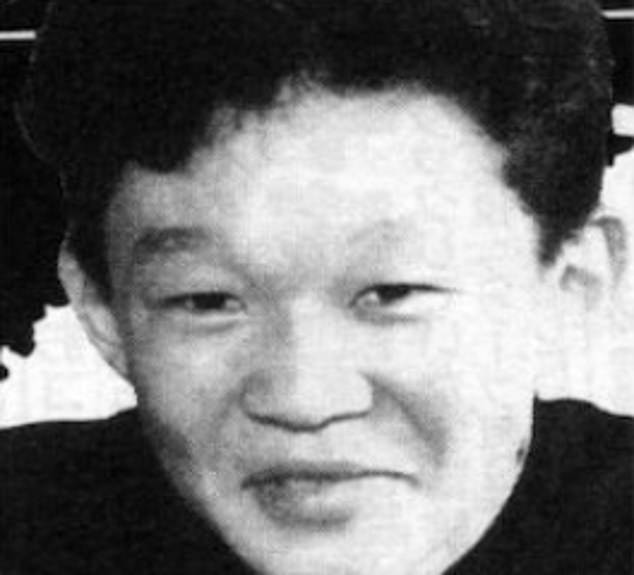

Hiroshi Miyano, 18, the ringleader, was handed the maximum sentence for causing bodily injury resulting in death, which was 20 years in prison

Acting on Miyano’s orders, Minato kicked Furuta off her bicycle and fled the scene as Miyano approached the student, pretending to be a witness to the incident.

He offered to walk her home and, after gaining her trust, took her to a nearby warehouse and threatened her. He told Furuta that he was a Yakuza member and that she would be spared if she followed his orders.

That same night, Miyano took Furuta by taxi to a hotel in Adachi, where he raped her.

He later called Minato’s house and bragged to Ogura about the rape, after which the 17-year-old told him not to let Furuta leave.

In the early morning hours of November 26, Miyano took Furuta to a park near the hotel, where Ogura, Minato, and Watanabe, 17, were waiting.

They told her they knew where she lived and that the yakuza would kill her family if she ever attempted to escape.

Minato agreed to allow Furuta to be confined in a room on the second floor of his house in Adachi so they could continue to gang-rape her.

On November 27, Furuta’s parents contacted the police to inform them of her disappearance.

To ensure that her parents would not continue to push for an investigation, the kidnappers forced Furuta to call her mother three times and convince her that she had run away and was staying with friends.

When Minato’s parents were in the house, Furuta had to act as his girlfriend, so as not to raise suspicion, but the group dropped the pretence when it became clear that Minato’s parents would not report them to the police.

The parents later claimed that they did not intervene because they were afraid of their son, who had been increasingly violent toward them.

On the night of November 28, Minayao and the others gang raped Furuta, after which Miyano used a match to burn her genital area.

Just less than a month later, Furuta attempted to escape her captors, which led to brutal punishment.

The group repeatedly punched her in the face and burned her ankles with a lighter.

They forced the teenager to dance to music while naked, engage in sexual activity in front of them, and stand on the balcony in little to no clothing in the middle of the night.

Over the course of her captivity, Furuta was subject to extreme acts of physical and sexual violence.

The gang of kidnappers forced her to drink large amounts of alcohol and milk, smoke two cigarettes at once, and inhale paint thinner fumes.

During one attack in the middle of the month, Furuta was beaten by the group after Miyano thought he had stepped in a puddle of her urine.

They then burned her thighs and hands several times with lighter fluid as punishment.

The gang of kidnappers was said to have inserted objects, including hot light bulbs, metal rods, bottles, and even an exploding firework, into her genital area. They also twisted off one of her nipples using pliers.

The boys hung her from the ceiling and beat her with golf clubs and iron rods, inflicting unimaginable pain.

This level of abuse continued to escalate throughout December, and by the end of the month, she was left severely malnourished.

Due to her injuries, she had become so weak that she could barely walk to the toilet, leaving her having to relieve herself on the room’s floor while in a state of extreme weakness.

She had also lost control of her urinary and bowel movements. Her appearance had been left so disfigured by the beatings, and her face swollen to the point of unrecognisability.

It was at this point, her wounds began to emit a foul odour. When the group of men and boys became too disgusted to continue sexually assaulting her, the severity of her beatings increased.

Then, on January 4, 1989, after allegedly losing a game of mahjong to Furuta the night before, Miyano decided to get revenge on the teenager.

He lit a candle and dripped hot wax onto her face, and placed two shortened candles on her eyelids.

Furuta was then lifted and kicked, dropped onto a stereo unit, and, while convulsing, was beaten by the group members who covered their fists with plastic bags.

An iron exercise ball was dropped onto her abdomen before Miyano carried out the final act of brutality, which would ultimately claim Furuta’s life.

After Miyano and Jo Ogura, 17, pictured, were arrested in another rape case, police uncovered their involvement in the disappearance of Furuta

The violent incident took place in the home of, Shinji Minato, who lived there with his parents. Minato received a sentence of five-to-nine years for his part in the gruesome murder

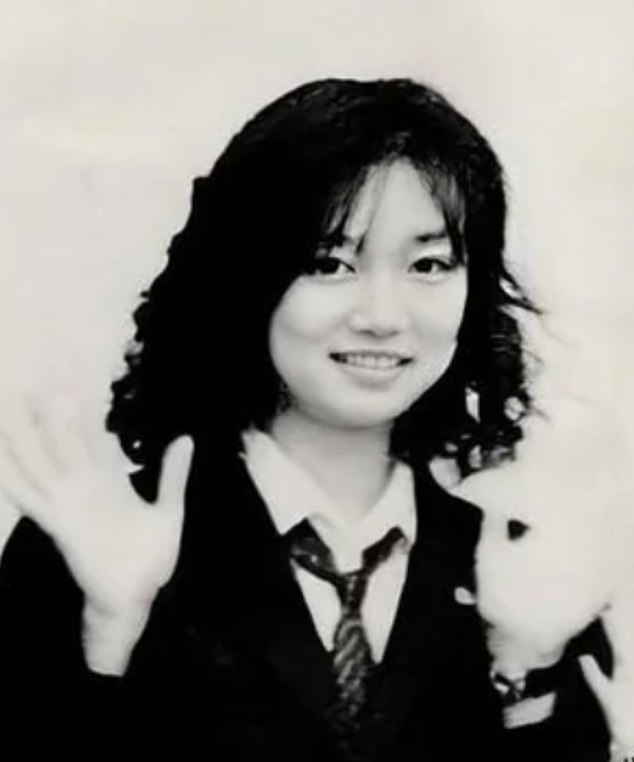

Yasushi Watanabe, then 16, received a term of between five and seven years for his part in the gruesome ordeal

During one attack in the middle of the month, Furuta was beaten by the group after Miyano thought he had stepped in puddle of her urine

Miyano poured lighter fluid on the young girl and set her on fire.

Furuta made weak attempts to put out the flames, but she soon stopped moving. She died two hours later at 10am.

Less than 24 hours after her death, Minato’s brother called to tell him that Furuta had died.

Out of fear their horrific crimes would be discovered, the group wrapped the teen’s body in a blanket, placed it inside a large travel bag, then put the bag in a 55-gallon metal drum, which they filled with wet concrete.

At around 8pm on January 5, the group drove to a vacant parking area near a construction site on the island of Wakasu, Tokyo, and abandoned the drum there.

On January 23, 1989, Miyano and Ogura were arrested for the kidnapping and gang rape of a 19-year-old woman in December 1988.

But when police interrogated Miyano, he wrongly believed that Ogura had already confessed to Furuta’s murder and that the police were aware this had taken place.

So he informed them of where they could locate Furuta’s body.

Authorities were initially puzzled by the confession, but on March 29, the drum containing Furuta’s body was recovered, and her body was identified via fingerprints.

Minato, Watanabe, Minato’s brother, Nakamura, and Ihara were also arrested.

All four defendants pleaded guilty to committing bodily injury that resulted in death, rather than murder.

But in July 1990, all were found guilty and sentenced by the Tokyo District Court for abduction for sexual assault, confinement, rape, assault, murder, and abandonment of a corpse.

Hiroshi Miyano, the main perpetrator of the heinous crimes against Furuta, was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Shinji Minato received a sentence of five to nine years, Jo Ogura was sentenced to five-to-10 years, and Yasushi Watanabe received a sentence of five to seven years.

Because some of the accused were under Japan’s legal age of full adult responsibility at the time, their identities were initially shielded under juvenile privacy protections.

But journalists from Japan’s Shūkan Bunshun tabloid uncovered their identities. They published them, arguing that the accused did not deserve to have their right to anonymity upheld, given the severity of the crime.

The discovery – and the confirmation of her death – galvanised public attention and horror.

The four young men most closely implicated in the killing faced criminal trials on charges ranging from abduction and sexual assault to murder and abandonment of a corpse.

Court proceedings in 1990 and 1991 resulted in guilty verdicts. Sentences, however, were not severe enough in the eyes of Furuta’s family and the wider public.

Hiroshi Miyano, the oldest of the main group, received the heaviest punishment – ultimately re-sentenced to 20 years in prison after appeal – while other defendants received significantly shorter terms.

The disparity between the brutality described in court records and the maximum juvenile-era sentences that could be imposed at the time fed a powerful sense among many Japanese citizens that the punishment did not fit the crime.

That outrage became one part of a national conversation about juvenile justice and whether the legal system properly balanced rehabilitation with punishment for the most violent offences.

Japan’s Juvenile Law – built around rehabilitation and confidentiality for offenders under a certain age – reflected a societal choice to treat young offenders differently from adults.

But when a crime is especially brutal, as Furuta’s proved to be, that philosophy collides with instinctive calls for retribution.

Many readers and commentators argued that, whatever the legal technicalities, the moral scale of the offence demanded life imprisonment.

At the heart of much of the controversy was the tension between protecting the identities of juvenile suspects and the public’s thirst for accountability.

Court rulings initially sealed the defendants’ names – tabloid journalists and some weekly magazines argued that the severity of the case justified breaking that principle.

The Furuta case is studied in law schools, debate forums and popular commentary as an example of the limits and moral dilemmas of systems that separate juvenile and adult offenders

In the years after the trials, the principal perpetrators served their sentences and returned to the world at different times.

Public attention remained – both in Japan and internationally – focused less on a tidy closure than on uncomfortable, unresolved questions.

Commentators and legal scholars used the case as a test case for juvenile law reform and for how societies should react when young offenders commit adult-level atrocities.

Media retrospectives and documentaries kept the episode alive in public imagination and policy circles, while occasional reporting on later arrests or criminal acts by some who had been released rekindled the pain.

The Furuta case is studied in law schools, debate forums, and popular commentary as an example of the limits and moral dilemmas of systems that separate juvenile and adult offenders.

Critics argued that the law at the time failed Junko – and the broader public – by limiting transparency and applying lenient punishments.

Defenders of juvenile protections warned that the instinct to treat every serious juvenile offender as an adult risks eroding principles that in many cases safeguard young people from a lifetime label for mistakes they might later outgrow.

The dilemma is not purely academic; it speaks to how communities invest in prevention, family support, mental health care, and policing strategies to stop violent paths before they begin.

There are several reasons the case persists in public memory.

First, the victim was an ordinary schoolgirl with a future. The ordinary-to-horrific arc will forever remain wrenching.

Second, the case cut across many civic fault lines – questions of youth delinquency, media ethics, judicial discretion, and parental responsibility.

Third, true-crime culture, documentaries, and podcasts have kept retelling aspects of the story for new audiences while often warning listeners about the intense emotional content.

And finally, unresolved social anxieties about crime and punishment mean that some cases never fully fade from national consciousness.