This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Schnapps decision

Yevhen Klopotenko is my new culinary crush. The first Ukrainian to be included in The World’s Best 50 Restaurants, he is also behind the listing of borscht as Ukrainian intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in 2022. Yevhen’s Kyiv flagship, 100 Rokiv Tomu Vpered (Fast Forward 100 Years), specialises in pre-Soviet Ukrainian dishes, including a lethally delicious smoked pear schnapps, to which I was introduced by Ada Wordsworth, one of the young curators of the Ukraine Pavilion at this year’s Architecture Biennale.

Ada is the founder of the charity KHARPP, operating since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in Kharkiv Oblast. The inspiration behind KHARPP came from an elderly woman who pointed out to volunteers delivering bread that such donations were useless, as her home was in ruins and the winter cold would kill her. Since then, over 900 homes in the region have been repaired, using local workpeople and traditional techniques, and KHARPP has now expanded into rebuilding accommodation for internally displaced Ukrainians throughout the country.

Alongside her courageous and urgent voluntary work, Ada is a brilliant photographer, whose documentary pieces will be on display at Arsenale until November. She travelled 30 hours overland to Venice with a quart bottle of Klopotenko schnapps in her backpack and between protesting the use of the Russian Pavilion for the Biennale educational programme and hanging the works at Ukraine’s found time to introduce my dinner guests to traditional Ukrainian toasts.

Yevhen is clearly a magician, as by the time the bottle was empty we were all singing raucously in Ukrainian. I can’t remember a word, but the bravery, passion and generosity of spirit of Ada and her colleagues is unforgettable. Ada writes about KHARPP at kharpp.substack.com — please consider subscribing.

* * *

The frenzy of Biennale opening week increases every year — more parties, more openings, more press launches. On the first day, I had over 50 possible appointments and made it to five. Plus, it always rains, and everyone gets the Biennale Bug, like Freshers’ Flu but with added Negroni hangover.

After three days of being stuck in confined spaces with hacking hacks, it was bliss to escape to this year’s best-kept Biennale secret, Caspar Giorgio Williams’ show of botanical artist Dominique Lacloche in the garden of Palazzo Soranzo Cappello. The setting for Henry James’ The Aspern Papers, this acre of eighteenth-century walled garden brimmed when I visited with clouds of sherbet-scented pink roses, with the works, sand-cast bronze sculptures of fig leaves, twining between tree trunks and beds of wild strawberries.

Delicate and ethereal, they create a slightly eldritch atmosphere, of enchantments taking place just out of sight. This is the third Venice garden show by C.G. Williams Art and a must-see for anyone visiting in July: a bewitching exhibit in one of the city’s most spectacular hidden spaces.

Bridging the divides

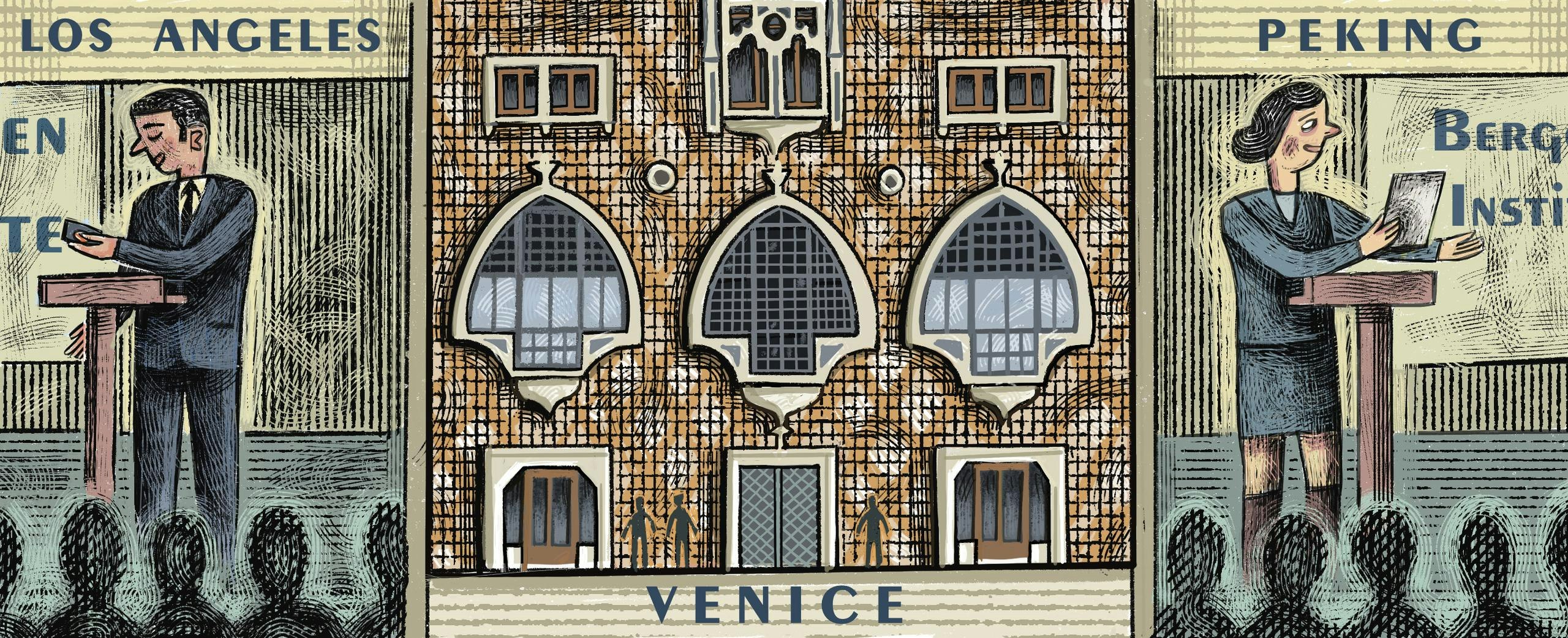

More amazing locations at two diverse but equally thought-provoking events organised by the brilliant Berggruen Institute, the outstanding interdisciplinary think tank whose European headquarters are housed at the splendid neo-Gothic Tre Oci palazzo on Giudecca. The building’s “three eyes” windows are an apt location for Berggruen’s tripartite collaborations between Venice, Los Angeles and Beijing and watching the sun set over the city through them, as the Italian minister of culture Alessandro Giuli presented his book Antico Presente, was particularly evocative.

Biennale president Pietrangelo Buttafuoco chaired a discussion on the palimpsests of Italy’s past, the layering of myth and antiquities which make up the country’s pre-Christian history. At the Aula Baratto, designed by modernist architectural icon Carlo Scarpa, the emphasis was on the future, with a lecture on leadership and traditional Chinese thought by Professor Yan Xuetong, discussing the challenges of a post-globalised world. Berggruen director Lorenzo Marsili is doing an extraordinary job of fostering independent and unexpected cultural encounters across conventional political divisions and positioning Venice as a “city of answers”, particularly refreshing in a place which is often seen as mired in its own somewhat despondent history.

• • •

Out on the razzle in Uzbekistan or at least the Biennale extravaganza hosted by the Uzbek Pavilion at Palazzo Soranzo Van Axel. Everything was gorgeous — the hovering banks of flowers suspended in the fifteenth-century fireplaces, the vast barrels of caviar (which caused the guests to lose all decorum), the whirling Uzbek drummers. Less so the hatchet-faced bouncers, complete with prison neck-tattoos, who reluctantly scowled me into the VIP room.

The VIP room was dry, mostly empty and Russian speaking; I spent two hours watching my friends whoop it up outside as trays of glorious jewel-coloured cocktails whizzed past the door, with a glass of water and my pathetically minute vocabulary, attempting to score a film gig in Tashkent. The ignominy of ligging felt particularly acute when an Uzbek layer-cake two metres in diameter paused tantalisingly at the entrance, only to be wheeled away to the frolicking hordes.

After the crowds have gone …

Boreana is a beautiful short documentary directed by two Venetian friends, glass master Emanuel Toffolo and artist Jordan Carraro, a survey of daily life on Burano, the rainbow-painted island whose soul is sadly being swallowed by the worst of hypertourism.

The film follows residents as they attempt to continue their lives in this tiny, remote village and discuss its past in dialect so impenetrable it requires subtitles in Italian. Its vivid, lingering images inspired an overnight trip into the lagoon, to experience Burano when the last tour groups have left: a long, soggy trip in my wheezy old boat but worth it to see a place which comes alive in the evening — old ladies and salty fishermen chatting over aperitivo in the square, hordes of children playing between the pink and blue cottages, poppies on the canal bank and, most precious of all after the Biennale commotion, silence.