Saturn‘s largest moon Titan has ‘slushy tunnels’ beneath its surface that could potentially harbour alien life, a new study shows.

Scientists at NASA and the University of Washington have analysed data captured by the Cassini space probe, which completed more than 100 targeted flybys of Titan.

They reveal that the faraway moon has ‘a slushy high–pressure ice layer’ similar to the melting Arctic that could hide extraterrestrial life.

What’s more, it means Titan may not have a waterworld–style liquid ocean under its frozen surface as previously thought.

‘Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we’re probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers,’ said study author Professor Baptiste Journaux at the University of Washington.

‘[This] has implications for what type of life we might find, the availability of nutrients, energy and so on.’

Around 3,200 miles in diameter, Titan is described by NASA as an icy world whose surface is completely obscured by a golden hazy atmosphere.

It is the sole other place in the solar system known to have an Earth–like cycle of liquids raining from clouds, flowing across its surface, filling lakes and seas, and evaporating back into the sky – akin to the water cycle of our planet.

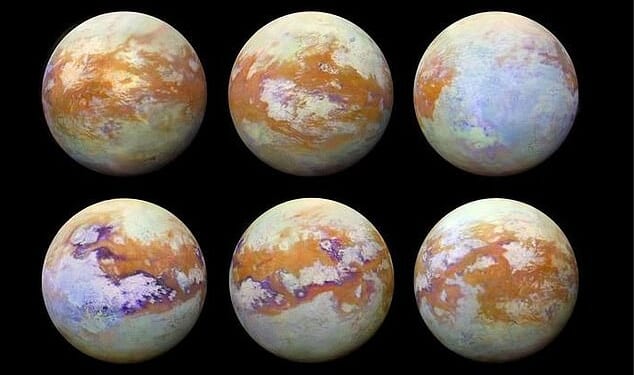

The six infrared images of Titan above were created by compiling data collected over the course of the Cassini mission. They depict how the surface of Titan looks beneath the foggy atmosphere, highlighting the variable surface of the moon

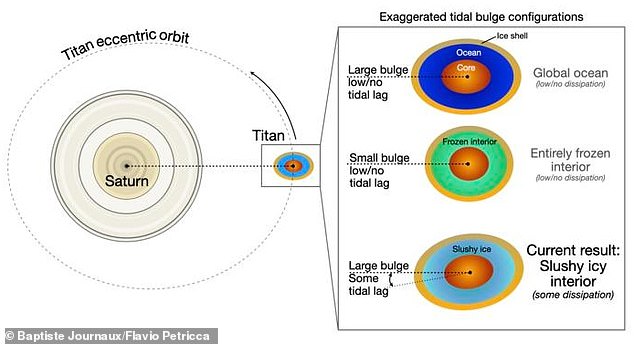

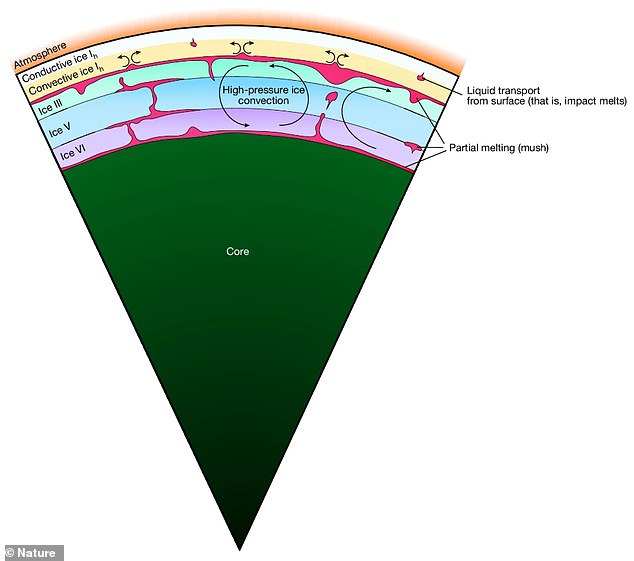

Titan’s frozen surface is thought to have water beneath it. According to the study, this is neither uniformly liquid, nor frozen solid, but slushy. This illustration shows the various ways Titan might respond to Saturn’s gravitational pull depending on its interior structure. Only the slushy interior produced the bulge and lag observed in the new study

NASA’s spacecraft Cassini launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida in October 1997 and spent two decades observing Saturn and its moons.

As Titan circled Saturn in an elliptical (not perfectly circular) orbit, the moon was observed changing shape depending on where it was in relation to Saturn.

In 2008, researchers proposed that Titan must possess a huge ocean beneath the surface to allow such significant ‘stretching and smushing’.

‘The deformation we detected during the initial analysis of the Cassini mission data could have been compatible with a global ocean,’ Professor Journaux said.

‘But now we know that isn’t the full story.’

For the study, scientists performed a reanalysis of radiation data acquired by Cassini using improved modern techniques.

Interestingly, they found that Titan’s shape–shifting or ‘flexing’ occurs about 15 hours after the peak of Saturn’s gravitational pull.

This time delay allowed scientists to estimate how much energy it takes to change Titan’s shape, allowing them to make conclusions about the moon’s interior.

Titan, imaged by the Cassini orbiter, December 2011. A thick shroud of organic haze permanently obscures Titan’s surface from viewing in visible light

Cassini is depicted here in a NASA illustration. Cassini launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida in October 1997

Essentially, the amount of energy lost, or dissipated, in Titan was ‘very strong’ and much greater than would be observed if Titan were to have a global liquid ocean.

‘That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses,’ said study author Flavio Petricca at NASA.

According to the study, Titan’s frozen exterior hides more ice giving away to pockets of meltwater (water formed by the melting of snow and ice) near a rocky core.

The model they propose in their paper, published in Nature, features more slush and quite a bit less liquid water on Titan than previously thought.

The discovery of a slushy layer on Titan has ‘exciting implications’ for the search for life beyond our solar system as it expands the range of environments considered habitable.

Although the idea of a liquid ocean on Titan was a promising indication of life there, researchers believe the new findings might improve the odds of finding it.

Analyses indicate that the pockets of freshwater on Titan could reach 68°F (20°C) – which is the optimal temperature for life on Earth to thrive.

Any available nutrients would be more concentrated in a small volume of water, compared to an open ocean, which could facilitate the growth of simple organisms.

Below Titan’s frozen exterior is more ice giving way to slushy tunnels and pockets of meltwater (water formed by the melting of snow and ice) near a rocky core

More could be revealed about the moon’s habitability after NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission to Titan launches in July 2028.

The Dragonfly lander is expected to launch in July 2028 and take six years to reach Titan, arriving by 2034.

Scientists are still reaping the rewards of the rich data obtained by the Cassini robotic spacecraft, which was active for nearly 20 years after launching in October 1997.

Cassini’s mission ended in September 2017 when it was deliberately flown into Saturn’s upper atmosphere before it ran out of fuel.

In 2019, Cassini data revealed that a lake on Titan is rich with methane and 300 feet deep.