Death, it seems, is a live topic in Westminster. On the one hand we have Kim Leadbeater’s ill-thought-out and chaotic Assisted Dying Bill; on the other Stella Creasy’s newest attempt to reform abortion laws so that women like Nicola Packer, who took pills while 26 weeks pregnant resulting in the death of the foetus, cannot be prosecuted.

They say politics is a deadly business, but this is taking it to a whole new level. It all comes down to ‘human rights’ of course.

In the case of these two complex and highly emotive issues, the rights of one group to determine the parameters of their own existence; and the right of another to place their own interests above those of another, voiceless group.

But the common denominator is the sanctity of life. That’s at the heart of the argument, or at least it should be.

Whether it’s a life burdened by disease or suffering or one that just happens to have been conceived at the wrong time or in the wrong circumstances, that is what we are debating here.

Except it’s not. Both these questions, it seems to me, are being approached from the point of view of expediency. To be more precise, political expediency. Which, given the paucity of moral fibre on the green benches, is a serious worry.

This government seems hell-bent on pushing through a framework that would not only facilitate ending human life at one end of the scale but also undermine its preservation at the other.

It’s a classic case of what the French philosopher Michel Foucault termed ‘necropolitics’ – the notion that equality is a fallacy and that it’s the state, and those in power, who get to determine the value (or otherwise) of people’s lives.

Kim Leadbeater, the sister of murder MP Jo Cox, introduced the Assisted Dying Bill to the Commons in October 24. It will return to the House on June 13

To an extent, this is already the case. In the NHS, value judgments are made about individuals daily. When resources are finite, decisions must be made about who is worth prioritising for treatment. The same principle is applied across many other areas of policy. Abortion is a classic case.

A woman’s right to choose is dressed up as a question of personal freedom, and to an extent that’s true; but abortion is also a very useful tool for minimising the number of unwanted children born to mothers who either can’t or won’t care for them, and the subsequent burden those children place on the state.

Better for a child not to be born at all, the logic goes, than to live a life of failure and misery at the expense of the taxpayer.

The assisted dying debate has been framed in a similar way: as a matter of self-determination, personal freedom. And that’s not entirely wrong: if a person is in terrible pain, or is subject to daily humiliations, or cannot experience any quality of life, then it is inhumane to insist they carry on.

But death – whether self-inflicted or imposed – should not become a matter of convenience. And there must be clear, enforceable boundaries to minimise the risk of abuse. That is why Leadbeater’s Bill is not fit for purpose: it fails to put in place sufficient safeguards. Leaving it up to so-called ‘experts’ – social workers or psychiatrists – is a recipe for disaster.

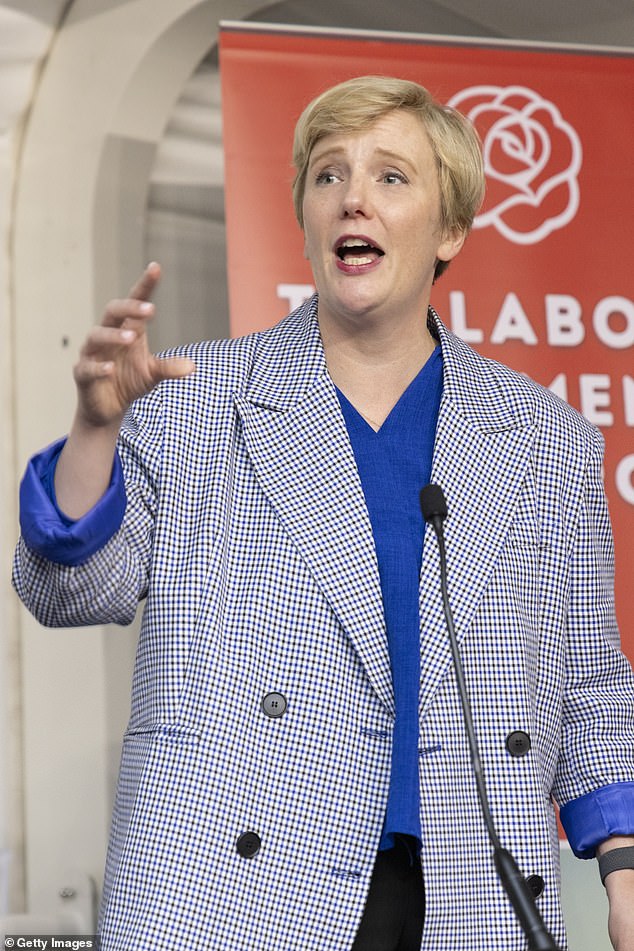

Labour MP Stella Creasy is attempting to reform abortion laws so that women like Nicola Packer, who took pills while 26 weeks pregnant resulting in the death of the foetus, cannot be prosecuted

Why? Well, just look at the suffering inflicted in the quest for ‘personal choice’ by the trans lobby. Countless young people condemned to brutal, medicalised misery by political dogma.

Look also at the situation with the rape gangs. That’s another example of how the Government judges that one group of people, in this case white working-class girls, is worth less than another, i.e. the men who abused them, and abandons them to their misery.

In both cases, the very social workers and other authorities who were meant to protect them did not, and in some cases even enabled the abuse. There is no reason to assume they would not do the same in the case of assisted dying to vulnerable people whose families wanted to facilitate their removal.

As for abortion, the law is clear as it stands. Women can access safe, legal abortion up to 24 weeks of gestation. When that law was devised, the chances of a foetus surviving outside the womb before that point was almost impossible.

Now, it’s far more plausible. Isn’t the humane thing to do to allow those babies the chance of life via adoption? To decriminalise the rules around abortion would effectively introduce state-sanctioned infanticide. It would also likely lead to further polarisation of the debate.

These are complex moral issues, and there are compelling arguments on both sides. The imperfections of the current rules are clear. But at no point has a cogent case been made for re-writing them. Until it is, what we have is, however unsatisfactory, better than any of the alternatives.

Goreous Giorgia

Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni who – as we saw last week from the reaction of Albanian prime minister Edi Rama – can bring grown men to their knees

Charisma is an important element in politics. Tony Blair, Barack Obama, Boris Johnson, even David Cameron: they all succeeded because, at some level, they had the right sort of swagger.

For female politicians, that kind of appeal often counts against them: it’s as though if a woman is in any way sexy, this somehow diminishes her ability to be taken seriously.

Not so Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni who – as we saw last week from the reaction of Albanian prime minister Edi Rama – can bring grown men to their knees. It’s good to see a woman politician embracing her undeniable femininity.

Having protested his ‘ignorance’ over the significance of a rat emoji in a pro-Palestinian post he shared, Gary Lineker declares he did not think biological males participating in female sports ‘would ever be an issue’.

He must think we’re as thick as BBC executives.

Cassie Ventura and Sean Combs, aka P Diddy, in Beverly Hills in 2017

I must confess to being gripped and horrified in equal measure by the trial of Sean Combs, aka P Diddy.

As for the notion that his accuser, Cassie Ventura, is in some way responsible for allowing herself to be abused in such a way, that is yet more proof of how little people understand the nature of coercive control.

Nor do they appreciate the terror that some men are able to inflict on some women.

But if there’s a special place in hell for Combs and his acolytes, there’s an even hotter seat reserved for the likes of Bonnie Blue, who perpetuate the myth that women enjoy being treated like toilet paper. They are both symptoms of the same vile disease.

The case of young British backpacker Bella May Culley, in custody in Georgia accused of drug smuggling, is every parent’s worst nightmare.

But it also highlights just how naive and arrogant young Brits abroad can be.

British law – as well as parents themselves – is endlessly indulgent of wannabe high rollers ‘hungry for success’ at any cost, as Culley described herself.

Britain may be soft on drugs and crime – but the rest of the world, as poor Bella is discovering, is no Notting Hill carnival.