Friday’S VJ Day 80th anniversary commemorations at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire may have been overshadowed in budget and scale by those to mark D-Day and VE Day in May – but they were no less moving.

In the presence of the King and Queen, the few surviving witnesses of that ‘forgotten war’, fought against the Japanese in the mosquito-infested jungles of Burma, gave their testimonies on a giant screen.

‘Imagine you’ve never been able to have a wash or a bath or a change of clothing for 12 months,’ said Thomas Jones, a 103-year-old ex-Royal Artillery bombardier from Salford. ‘And on top of that, you had to fight the Japanese!’ That raised a bittersweet laugh.

He went on. ‘You never saw them until they were attacking you. I saw this Japanese officer. He’s got his sword and he’s running straight at me, and I’m thinking, “This is my last day.” Well, all of a sudden, a Gurkha soldier came round the back of me and shot him. The Gurkhas – the greatest!’

Very sadly, Mr Jones missed the ceremony. He had passed away just the day before, which made his words even more poignant.

For me especially so, since that experience of his was almost identical to that of one of my grandfathers, Arthur, who also fought in that terrible campaign.

Arthur, too, survived an attack from a Japanese officer, who came at him with his sword, intending to slice his head off. Arthur shot him at point-blank range – but later told my Uncle Tim that the officer ‘came at me every night for years’. I wonder: did Arthur and Mr Jones know each other? They would have been about the same age.

Unlike Mr Jones, Arthur did not live a long life. He died over three decades ago, when I was still in my 20s. I barely knew him, save as a quiet man with a rather stern face and hooded, sad eyes, who would smoke cigarettes in the garage of his tiny house in Bickley, south-east London, sipping surreptitiously from a bottle of gin.

To me, as a young child, Arthur represented order and reliability, the precise opposite of my father, who was a chaotic figure, writes Sarah Vine

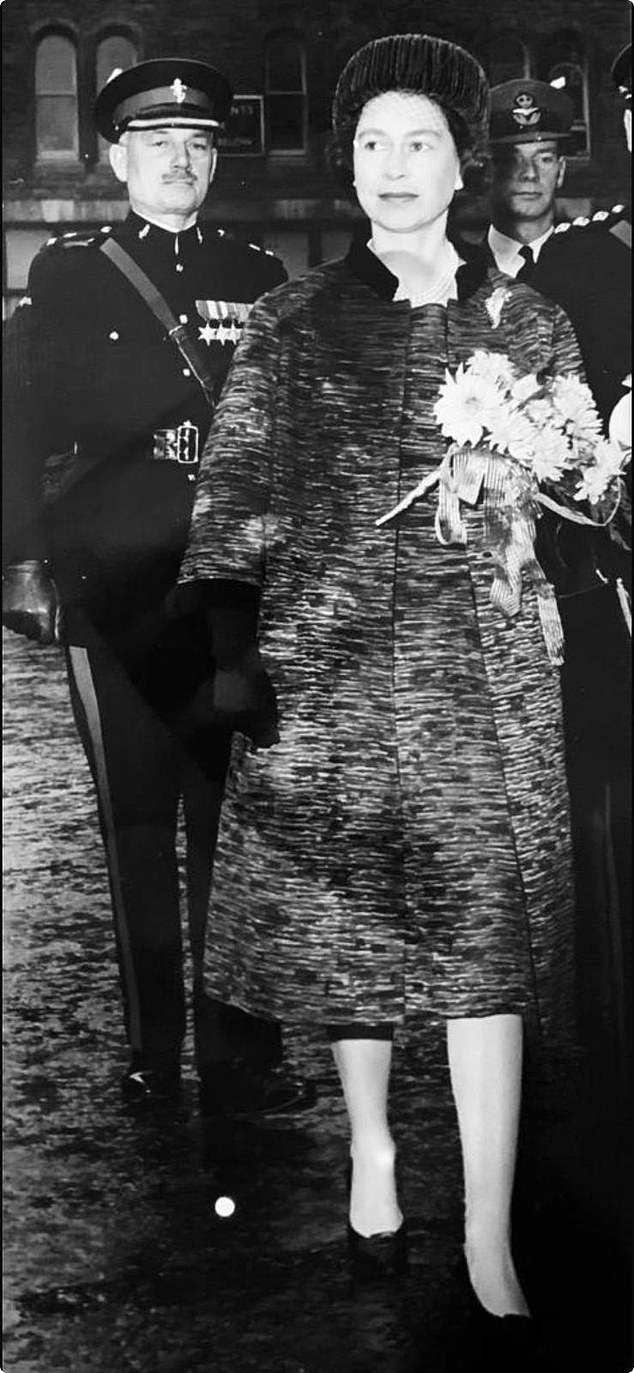

Arthur pictured with Queen Elizabeth II at Sterling Castle in the early sixties

King Charles and Queen Camilla were moved to tears during the VJ Day 80th anniversary ceremony at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire on Friday

He was always kind and indulgent of me, his first grandchild. He drank Camp coffee and smelled of Imperial Leather and, even in retirement, he maintained a bristly military moustache (he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and once escorted the late Queen around Stirling Castle, one of the proudest moments of his life).

He would get up at dawn every day to carry out his household chores, assigned by my grandmother, with military precision.

To me, as a young child, he represented order and reliability, the precise opposite of my father, who was a chaotic figure. I never knew what horrors my grandfather had endured because he would never have dreamt of telling me. He wouldn’t have considered it appropriate: he was firmly of the ‘never complain, never explain’ school.

But as I grew older, I began to realise that beneath the military rigour, all was not well. Arthur drank, and it was a problem. It took his health, his marriage and eventually his dignity.

Later, when I was in my early 20s, and shortly before the alcohol finally killed him, I would visit him and he would slip me a fiver, asking me to buy him a forbidden bottle from the off-licence.

I saw him then as a forlorn, rather pathetic figure. I wish I had had the intelligence and the foresight to understand him better, to see what had brought him to that state, and to truly comprehend the price he had paid, along with so many of that generation, for my charmed existence.

Veterans of that campaign in the Far East – such as the Chindits, named after the Burmese word ‘Chinthe’, mythical lion-like creatures often seen at the entrances of temples – were told not to speak of it, and many, like my grandfather, did not. But that did not mean that their experiences were not seared into their souls.

Many came home profoundly changed, often unrecognisable to the families they had left behind. Piecing together snippets of family history, I have no doubt that Arthur’s experiences scarred him irrevocably. When he returned he was no longer the person my grandmother had married. They went on to have three children, but the damage was done. The demons that followed him home haunted them all their lives.

What little I know of his time there comes via Uncle Tim, Arthur’s only son. One night, he and Tim were watching a documentary about the Chindits – the Special Forces troops dropped behind Japanese lines – on TV and Arthur suddenly said: ‘Hang on, I knew him,’ pointing at a face on the screen. ‘I served with him!’

As that evening wore on, prompted by that memory, he unburdened himself to my uncle. Besides Burma, he had served at Dunkirk, in Crete and Tobruk, and he recalled heartbreaking tales of young friends and revered superiors being killed beside him in those bloody battles.

But it was when talking about Burma that, Tim says, Arthur started to stumble and stammer.

In common with so many others, Arthur, it turned out, had had to do the worst thing an officer ever has to do behind enemy lines: he had been forced to hasten the deaths of some of his own men. It was an act of kindness because they were too sick or badly wounded to carry on and no one wanted to end up in the hands of the Japanese.

‘I did some things you shouldn’t have to do,’ he said haltingly to my uncle. ‘Nobody can understand.’ But, he added, embracing his son: ‘I would do it all again if it meant you never had to.’

The only inkling I ever had of his pain was when once, visiting us for a holiday in Italy, I woke in the middle of the night to find him pacing wildly, mumbling about ‘dark forces’ that were coming to get us. He was clearly in the grip of some sort of delirium. His intensity was frightening, the lost look in his eyes unfathomable.

I’m ashamed to say I never understood. And I don’t think anyone really did.

My grandfather never thought of himself as a war hero. He never glorified or revelled in his exploits. In fact, he despised war, precisely because he saw so much of it and at such close quarters. And he didn’t hate the enemy. He wasn’t anti-German, or anti-Japanese, despite it all; he just never wanted anyone else to experience what he had seen and done.

I realise now that, beneath the bristles, Arthur was a sensitive, thoughtful man, utterly repulsed by the brutality of war. And I see that sentiment reflected in the few veterans who survive today.

That is why their testimonies, and their memories, are so important. In a world where people are so quick to anger, where conflict can ignite over seemingly the most trivial of issues, they remind us of what war really is. Ugly, heartless, inglorious.

I raise a glass to you, Arthur, and all your companions on this anniversary of VJ Day. I wish I had been wiser, kinder, less self-obsessed and stupid while you were still alive. I am sorry I was not.

Most of all, I hope that when the last of you is finally gone, the world continues to remember. Not just because we owe you an inestimable debt, but also because we simply cannot afford to forget.