Abandoned by her parents, Fu Lian Doble was left outside a bank on a wintry Boxing Day in 1999. Or at least that is according to records kept by the Chinese orphanage that took her in. But in adult life, having been adopted by a British couple she calls mum and dad, she has discovered this is almost certainly a lie because the orphanage has been exposed for buying and selling babies for international adoption.

‘It really hit home how much of our identity is grounded on just a few pieces of paper, and we can’t even trust those,’ she says.

Fu is one of some 150,000 Chinese children who were sent overseas over three decades, their lives the collateral damage of the Communist regime’s ruinous one-child policy.

Thousands like Fu have been adopted by British couples, led to believe these babies – almost all girls – had been disowned by their birth parents. But as a new book, Daughters Of The Bamboo Grove, exposes, the truth was often far darker, as the brutal hand of the Chinese state snatched babies, quite literally, from their mothers’ arms.

Fu, who works in marketing and communications at Manchester University, had long been keen to discover her true origins when she received a message from China that her older sister was searching for her.

‘I was confused,’ Fu says. ‘I don’t have an older sister. What’s going on?’ She soon realised the sister she never knew existed had matched a photo of Fu as a baby – which she had posted on a website that helps facilitate reunions – with an identical picture given to her adopted parents by the orphanage.

Fu Lian Doble, who works in marketing and communications at Manchester University, is one of some 150,000 Chinese children who were sent overseas over three decades

That was last summer and after several months and extensive DNA tests, she met her birth family, first by video link and then in April in person at their home in China’s Hunan province.

She says: ‘It was very surreal and it’s still something that’s hard to get my head around, particularly because my whole identity has been rooted in never knowing.’

The circumstances of acquisition by the orphanage are still vague. Her parents lived in a poor rural community and she was a twin, delivered prematurely and in secrecy at an aunt’s house. Her twin died and her mother was lucky to survive because of complications during labour. In the trauma, Fu was entrusted to a neighbour who is suspected of giving her to the orphanage – whether for money or through fear of China’s tyrannical birth control authorities, Fu does not know.

When her mother recovered, all she had of her new baby was the photo from the orphanage – the one that was eventually matched.

Fu’s story mirrors that of Fangfang, the subject of Daughters Of The Bamboo Grove. Fangfang was almost two when the Chinese authorities burst into her home and ripped the terrified toddler from her aunt, who was hiding the girl for her sister. The author of the book Barbara Demick, a former foreign correspondent with the Los Angeles Times, follows the desperate attempts of Fangfang’s family, impoverished migrant workers, to trace their daughter, one of thousands of babies seized across China between 1979 and 2012.

Officials forged documents saying the children were orphans, then split lucrative adoption fees with orphanages. The state viewed Fangfang’s parents as serial offenders. They already had two daughters – when the second was born, officials demolished part of their home as punishment as they couldn’t pay a crippling fine.

When Fangfang’s mother became pregnant for a third time, she was terrified but determined to keep the child. That fear intensified when she gave birth to twins in secret in a bamboo grove near their home. An aunt and uncle took in Fangfang to hide her but the vast family planning bureaucracy had snitches in every village.

Fangfang was adopted by evangelical Christians in Texas, who called her Esther. Only as an adult, with Demick’s help, did Fangfang/Esther reconnect with her birth family – and the identical twin she never knew existed.

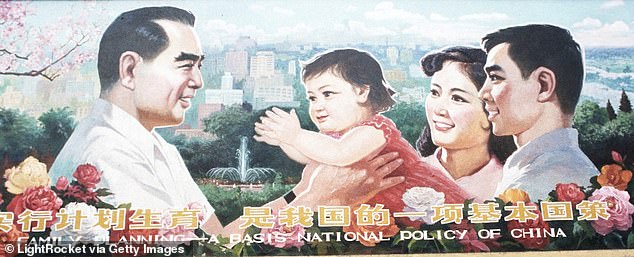

A 1985 billboard promoting China’s one-child policy, which was introduced in 1979

Their initial contact was nervous as they chatted on a Chinese video app. The awkward questions and stilted answers via an interpreter revealed the enormous gulf that separated their upbringings.

Esther was an aspiring photographer, every part the middle-class American girl; her twin Shuangjie, was a teacher trainee, but shy and embarrassed to reveal the comparative poverty of the room she shared with fellow trainees.

Later they met, together with birth and adopted parents, in China, which is when the tears flowed – tears of guilt, happiness and reconciliation. For these families at least, a relatively happy ending to a wrenching saga.

China’s one-child policy was introduced in 1979 but to call it ‘policy’ does not come close to capturing the terror unleashed over some 35 years – till it was replaced with a two-child policy in 2016, which was upped to three in 2021 – in the name of population control.

Its architect was Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) chairman too often blindly hailed a reformer. To Deng, fewer babies meant fewer mouths to share the fruits of his economic ‘opening up’. It was enforced with a cruelty and fanaticism equalling that of his predecessor Mao.

At its heart was a monstrous bureaucracy, bigger than the police and military and employing millions, with spies in every village. This was not so much ‘family planning’ as an instrument for the zealous control of the population through extreme punishments.

Sanctions for having more than one child included fines of up to six times annual earnings, beatings and the demolition or confiscation of homes. Women were sterilised or fitted with intrauterine devices.

Many were hauled away for barbaric late stage abortions, during which doctors would often induce labour and then before the baby’s feet emerged they would kill the baby with an injection of formaldehyde into the cranium. This was considered an ‘abortion’, since the baby was still partly in the womb.

Family planning departments ran mass campaigns for sterilisation or fitting IUDs and were given quotas for the number of births in a county or township. Women had to report on their menstrual cycle.

The sister Fu never knew existed had matched a photo of Fu as a baby – which she had posted on a website that helps facilitate reunions – with an identical picture given to her adopted parents by the orphanage

Officials imposed collective punishment on villages deemed to have exceeded their quota – a policy designed to incentivise people to squeal on neighbours trying to conceal pregnancies.

This became a vast money-making machine for local governments, generating some $3billion to $5 billion annually in fines – and encouraging those who might have felt squeamish about their methods to look the other way.

The slogans plastered on village walls left little room for imagination: ‘Kill all your family if you don’t follow the rule’, ‘If you escape [sterilisation], we’ll hunt you down. If you want to hang yourself, we’ll give you the rope’.

There were supposedly exceptions to the rules, such as those for ethnic minorities – who would have been wiped out by the policy – and some categories of farmers but interpretation was left to the corrupt family planning officials.

One woman in rural Shanxi province assumed she was entitled to a second child but officials disagreed and when she failed to stump up a $6,000 fine she was forced to abort her baby. Her sister-in-law took a photo on her mobile phone of the devastated young woman lying in bed beside what appeared to be a perfect newborn baby – only it was dead.

The photo went viral – before it was deleted by the CCP’s censors. That was 2012, four years before the scrapping of the policy. By then, outrage was growing and even Chinese scholars were warning of a demographic crisis in the making. But they were doing so quietly since to cross the CCP invited severe retribution.

Worse, increasing availability of ultrasound scans to determine a baby’s sex in the womb led to widespread aborting of girls because of a cultural preference for boys and a belief that in the absence of a meaningful social safety net in the Communist utopia, a male would be more useful in providing for a family in their old age.

Demick reports that at the height of this madness, some provinces saw births of as many as 140 boys to every 100 girls.

Demographers calculate up to 60 million girls are missing – aborted, killed or abandoned – as a result of the policy. Even China’s researchers have recognised the appalling cost, with Jiang Quanbao from Xi’an Jiaotong University estimating 20 million baby girls went ‘missing’ between 2002 and 2008.

Demographers calculate up to 60 million girls are missing – aborted, killed or abandoned – as a result of the policy

This has resulted in a generation of ‘leftover’ men who cannot find wives, fuelling an epidemic of ‘purchasing’ brides from the poorest regions of south-east Asia.

This has included impoverished teenagers from Myanmar, procured by brokers, given little choice as to who they marry and often kept in near slavery.

Those ‘brides’ who escaped and ran to Chinese police were sometimes jailed for immigration violations rather than being treated as crime victims, according to a report by Human Rights Watch.

During a recent visit I made to the border regions of Vietnam, the Vietnamese police busted a ring smuggling girls under 16 to China for sale as brides, and witnesses described a horrendous accident along the mountainous border when 11 people, mostly trafficked young women, were killed when their vehicle flipped into a gully.

By 2022, the demographic timebomb had begun to detonate. China’s population shrank for the first time since the famine of 1961, with the birth rate reaching the lowest level on record. An estimated 400 million people – almost a third of the population – will be aged 60 and over by 2035.

This will put severe strain on the country’s overwhelmed hospitals and underfunded pension system – against the background of a stagnating economy. The government fears that by 2050, the workforce to support the country’s elderly will have shrunk from a 2015 figure of 911 million to 700 million. Other countries have turned to migrants to tackle demographic challenges but China is deeply hostile to immigration, with a deep-seated belief in racial purity.

China’s scrapping of the policy came too late. By the time the three-child system arrived in 2021, women were deciding to have smaller families. As happened in Japan, urbanisation, changing lifestyles and soaring costs of raising a family played a part.

But the Communist Party is incapable of keeping out of their bedrooms. The bureaucrats have switched from the barbarity of the one child policy to bullying women into having more children.

Women have reported receiving phone calls from government workers demanding to know if they are pregnant and urging them to have more babies. One woman was quizzed about when she had her last period.

Of the rogue orphanages, the CCP claims to have cracked down on the underground markets that were buying and selling children.

Meanwhile, specialist search organisations, using DNA matching, are helping international adoptees like Fangfang and Fu look for information about their biological parents and the circumstances of their adoption, though their success rate is 3 per cent, Fu was told when she started searching.

But in being reunited with their birth families, they are the lucky ones amid generations caught up in one of the cruellest, costliest, misguided policies the world has ever seen – and one that will haunt China for decades to come.

Ian Williams is author of Vampire State: The Rise And Fall Of The Chinese Economy, published last year by Birlinn.