One of the failings of the British left is to take the Conservatives seriously when they claim to be the party of low taxes. Having talked themselves into believing that the Tories spent 14 years under-taxing businesses and the rich, the Labour Party came into power thinking that there were billions of pounds lying on the pavement waiting to be picked up. It only took one Budget for this idea to unravel. Before the election, a tax on non-doms was the magic money tree that would pay for free school breakfasts and fix the NHS. Today, the only question is whether the tax will raise a trivial sum of money or lose the government money. Hiking National Insurance contributions for employers seemed like a pain-free way of raising £25 billion, but it was soon understood as a tax on employment and, with business confidence collapsing, it no longer looks like such easy money.

There is a dawning realisation that the Conservatives, who raised the tax burden to the highest level in 70 years through a combination of higher rates, new levies and fiscal drag, did not walk the walk as the party of low taxes. If they didn’t introduce a new tax or increase an old one, it was not because they were on the side of “the rich” but because they could see that it would do more harm than good. While the far-left call for a wealth tax in the deluded belief that it would raise £25 billion a year, the rich are already scarpering under the weight of existing taxes.

In practice, the government has a choice between raising taxes such as VAT and income tax which have a broad base or cutting the size of the state. The Cakeist electorate want neither and nor does the Labour Party and so the government continues to search for easy pickings.

One ruse, announced last week, is to raise the tax on online betting. The government did not quite put it like that. It said it wants to explore the possibility of a “single tax for UK-facing remote gambling”, but since the tax on online casinos is 21 per cent while the tax on online bookmakers is 15 per cent, the only realistic outcome is an increase in the latter to match the former.

Why the disparity? It all goes back to the crusade against fixed-odds betting terminals. Remember them? They were supposed to be the crack cocaine of gambling and had to be banished from the kingdom. The only problem was that they produced a lot of revenue for the government and the Chancellor of the day — Philip Hammond — was reluctant to part with it. When the pressure to get rid of the dreaded FOBTs became too much, he announced a hike in Remote Gaming Duty for online casinos from 15 per cent to 21 per cent. This made a certain amount of sense. It was obvious that punters would switch to online casinos if they couldn’t play roulette in betting shops, and the amount of revenue the tax would bring in was roughly equivalent to what would be lost when FOBTs disappeared. Moreover, online slots were seen as a booming industry that could take the hit.

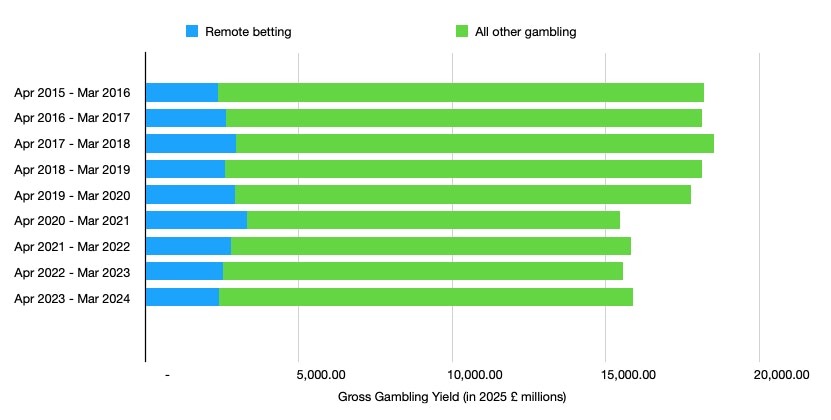

The rationale for raiding the online betting industry is less compelling. Its margins are tighter and it includes a lot of small and medium sized companies. The government’s argument is that sports betting is a flourishing industry that is growing exponentially, but that simply isn’t true. In its consultation document, HMRC claims that Gross Gambling Yield (which roughly equates to revenue) has risen by 208 per cent since 2014/15 in the remote gaming sector while the number of bricks-and-mortar gambling premises has fallen by 29 per cent. The message is clear: the online gambling industry is cleaning up at the expense of the traditional gambling industry.

This is crafty accounting for several reasons. Firstly, whilst it is true that the number of active gambling venues in Britain has fallen from 11,758 to 8,329 in the last ten years, the vast majority of the premises that have closed are bookmakers — and they have closed as a direct result of the crackdown on fixed-odds betting terminals. It is a bit rich for the government to be shedding tears over such an obvious and predictable consequence of its own actions (Labour hated FOBTs even more than the Conservatives).

Secondly, HMRC are comparing apples and oranges by using 2014/15 as its baseline. Prior to 2015, many online gambling companies were based overseas and their revenue was not counted in the data. The Gambling (Licensing and Advertising) Act of 2014 required all offshore gambling companies trading with UK customers to be licensed by the Gambling Commission, taxed by the British government and comply with British gambling regulation. As a result, online gambling revenue, as recorded by the Gambling Commission, nearly doubled between 2014/15 and 2015/16, but this did not reflect a genuine increase in expenditure. All that really happened is that spending that had previously been hidden became visible. Figures from before 2015/16 therefore cannot be compared with any figures produced since, because the older data greatly underestimates the amount that was actually being spent online.

Finally, HMRC are doing something that is very common in discussions about the gambling. They are ignoring inflation. No one would dream of comparing government spending ten years ago with government spending today without adjusting for inflation which, as you may have noticed, has been considerable in recent years. When it comes to gambling, there is a strange reluctance to factor in the cost of living.

But if we look at the figures in real terms (i.e. after adjusting for inflation) it is clear that overall gambling spend has declined significantly since 2020, and spending on online betting has not grown at all since comparable records began in 2015/16. All those adverts for online bookmakers are fighting over a static market. The only part of the online gambling sector that has grown in real terms is online casinos, with Gross Gambling Yield rising from £3.2 billion in 2015/16 to £4.4 billion last year, but online casinos are already taxed at 21 per cent.

If Remote Gaming Duty for online betting were to be raised to 21 per cent, it would come on top of Corporation Tax, which was increased to 25 per cent under the low-tax Tories, and on top of the new gambling levy which will take 1.1 per cent of these companies’ turnover. Since gamblers choose how much they spend, betting companies cannot pass these costs onto customers through higher prices. They can either get out of the market or offer worse odds. Gamblers, meanwhile, are finding it increasingly tempting to use unregulated websites from abroad which are not weighed down by a heavy tax burden and with whom the Gambling Commission is playing an endless game of whack-a-mole.

None of this is conducive to the Treasury’s stated aim of having a gambling industry that is “sustainable, offers jobs and brings social value to the UK.” On the contrary, it looks more like the government is intent on kneecapping one of the few industries in which Britain can plausibly claim to be a world leader.