Technology and development are saving lives in disaster zones.

In the past days, the world has been shaken—literally—by several natural disasters: the devastating floods in Texas in June 2025, which displaced thousands; the 5.7 and 5.8 magnitude tremors that struck Guatemala on July 8 and 29, respectively; a 7.3 magnitude earthquake in Alaska that triggered tsunami warnings throughout the North Pacific; and, most recently, a massive 8.8 magnitude earthquake off the coast of Russia on July 29—one of the strongest in recorded history—prompting tsunami alerts across the Pacific.

It’s natural to feel that disasters are becoming more frequent. But that impression might reflect our improved ability to detect, report, and record these events—and the fact that, in our 24/7 global news cycle, we now hear about incidents in distant countries almost instantly—rather than an actual surge in their number. What we can say with confidence is: despite a growing global population, people today are more likely to survive disasters than a century ago.

Not About the Number of Disasters, But Survival

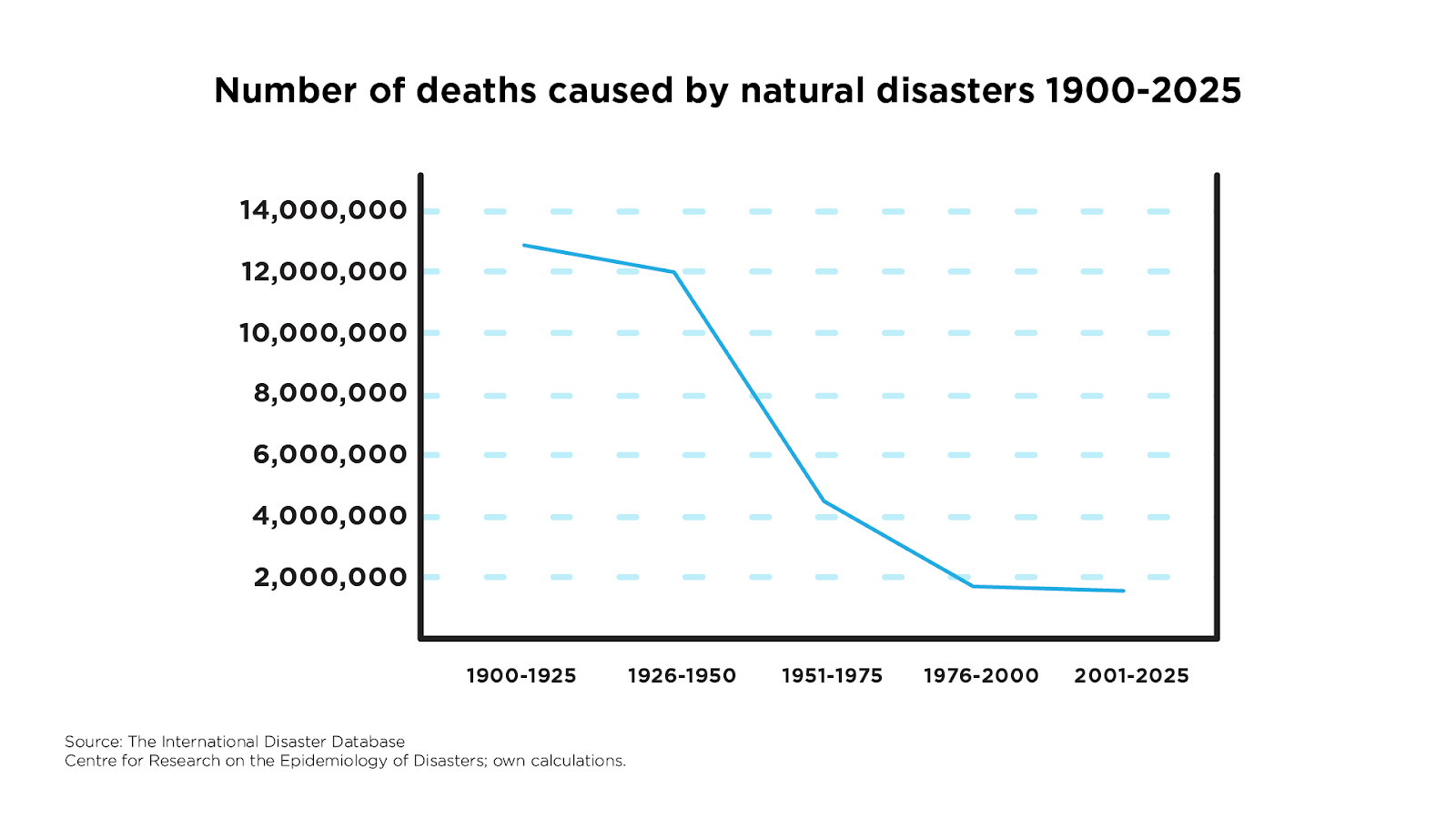

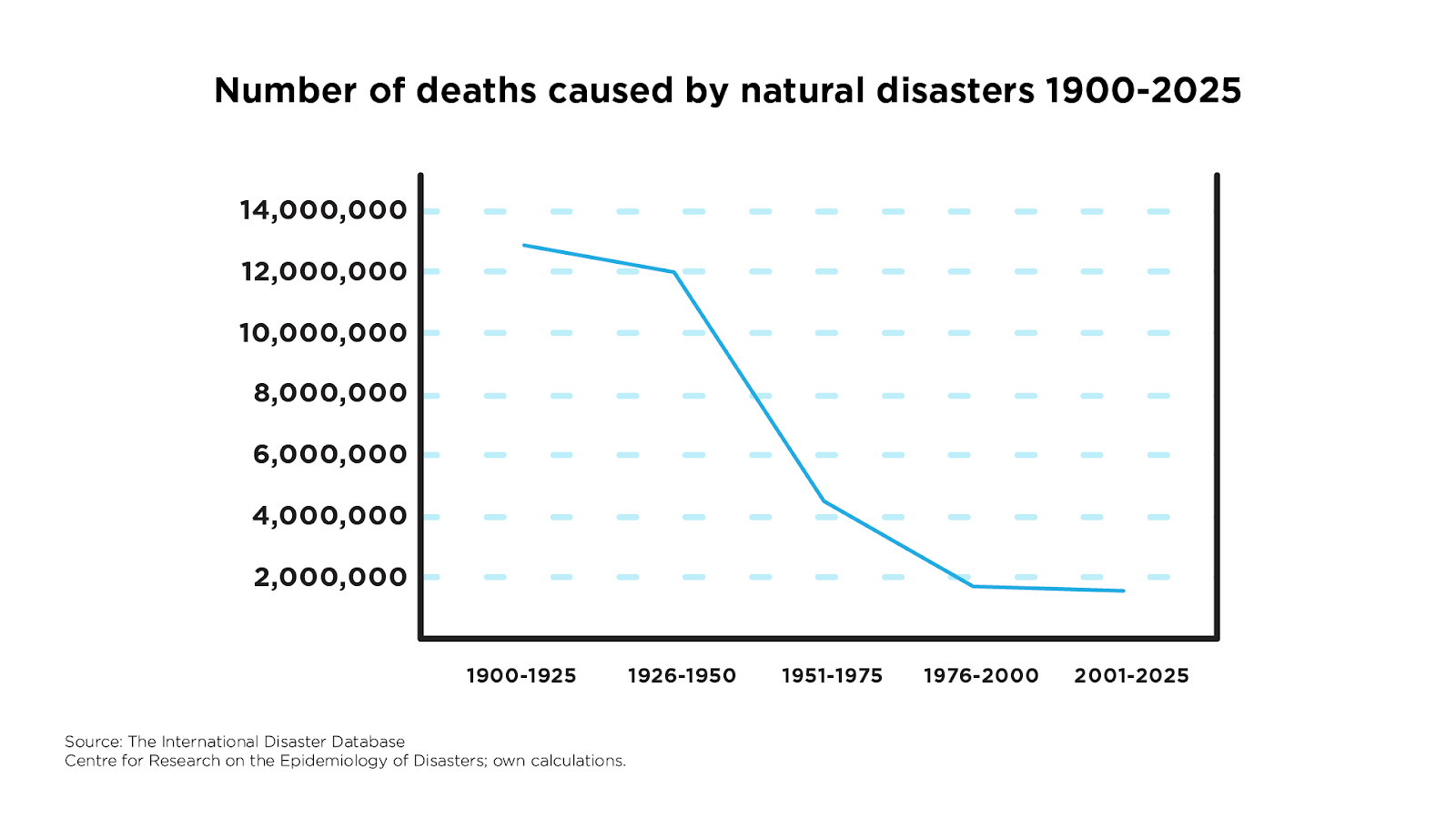

According to data from the International Disaster Database, disaster-related deaths dropped dramatically over the last century. Between 1900 and 1925, over 12.8 million people died from natural disasters. In contrast, between 2001 and 2025, that number dropped to just 1.6 million, representing an 88% decrease, even with a global population that more than quadrupled between those same periods.

That means that the average number of deaths per disaster has fallen dramatically. In the early 1900s, an average of 60,000 people died per disaster. Today that is just 163, a 99.7% decline.

This reflects a century’s worth of technological improvement and coordination in risk mitigation.

Why Are Fewer People Dying?

One key reason is technological advancement: early warning systems, weather satellites, digital telecommunications tools, and climate prediction platforms have saved millions of lives by facilitating timely evacuations. Earthquake-resistant construction methods, simulation models, and resilient infrastructure have dramatically reduced exposure to risk.

Equally important is the role of economic development and better-planned urbanization. Rising living standards have allowed more people to live in safer conditions and access better education, information, and emergency services.

In this sense, the figures support the thesis of economist Julian Simon, who argued in The Ultimate Resource (1981) that human ingenuity—not natural resources—is the most valuable resource for addressing humanity’s great challenges. According to Simon, creativity, innovation, and knowledge accumulation in free societies enable us to overcome threats that would have been lethal in the past. The impressive 88% decline in deaths from natural disasters since 1900 offers strong empirical validation of this view: not only do we face more disasters, but we survive them better thanks to what he identified as the true source of progress.

A Lesson from History

This does not mean that the danger has disappeared and that disasters no longer pose a threat. With climate pattern changes and urban concentrations, the stakes remain high, especially for low-income countries still developing their infrastructure and response systems. But if the last century proves anything, it is that technological and economic progress offers not just prosperity but protection. In many cases, it has a profoundly humanitarian impact, more so than any public policy measure.