This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Opinion is divided on what to call the silverware that the Test cricketers of England and India are contesting this summer. Will the home side’s most prolific wicket-taker or the tourists’ heaviest run-scorer get top billing? The Indian press and BBC went for the Tendulkar-Anderson Trophy; Cricinfo preferred Anderson-Tendulkar. Knowing the money-obsessed world of modern cricket administration it will probably become the Tendulkar-Anderson Trophy Adornment in order to get sponsored by an Indian steel company.

No one disputes that they deserve the honour. Sir James Anderson’s 188 Tests is beaten only by Sachin Tendulkar’s 200. The Englishman took 704 wickets, the most by a seam bowler; the Indian scored a record 15,921 runs. Tendulkar hit seven Test centuries against England; Anderson took six five-wicket hauls against India. Naming the prize thus follows a modern fashion: England plays West Indies for the Richards-Botham Trophy and New Zealand for the Crowe-Thorpe; Australia and India contest the Border-Gavaskar. The Ashes remains the Ashes, after Ashley Mallett and Ashley Giles. Possibly.

One man used to be enough to cover both nations. When they wanted a trophy in 2007 to mark 75 years since the first Test between England and India, they called it after the eighth Nawab of Pataudi, an Indian prince who played six Tests, three for each country. He made a century on his debut for England in Sydney in 1932, then captained the land of his birth in their first postwar series in 1946.

Pataudi was one of 17 men to play Test cricket for two countries, the first being Billy Midwinter who played four Tests for England and eight for Australia. “In Australia he plays as an Englishman; in England, as an Australian,” an Australian magazine reported. “And he is always a credit to himself and his country, whichever that may be.”

Midwinter was often conflicted. In 1878, W.G. Grace kidnapped him from the Australian dressing room at Lord’s, where he was waiting to face Middlesex, because he had promised to play for Grace’s Gloucestershire against Surrey at the Oval. Midwinter died in a mental asylum aged 39, perhaps of confusion.

Pataudi was a title forged in the British Empire, which, along with the Nawab’s Muslim faith and his relation by marriage to Pakistan’s first prime minister, may explain why the trophy has been rebranded, yet it is a fascinating story. The first Nawab was an Afghan warlord who was given the princely state of Pataudi, near Delhi, by the East India Company in 1804. His seventh successor, Mohammad Iftikhar Ali Khan, inherited the title when he was 7 and learnt cricket from an Oxford-educated tutor who recommended he study at Balliol.

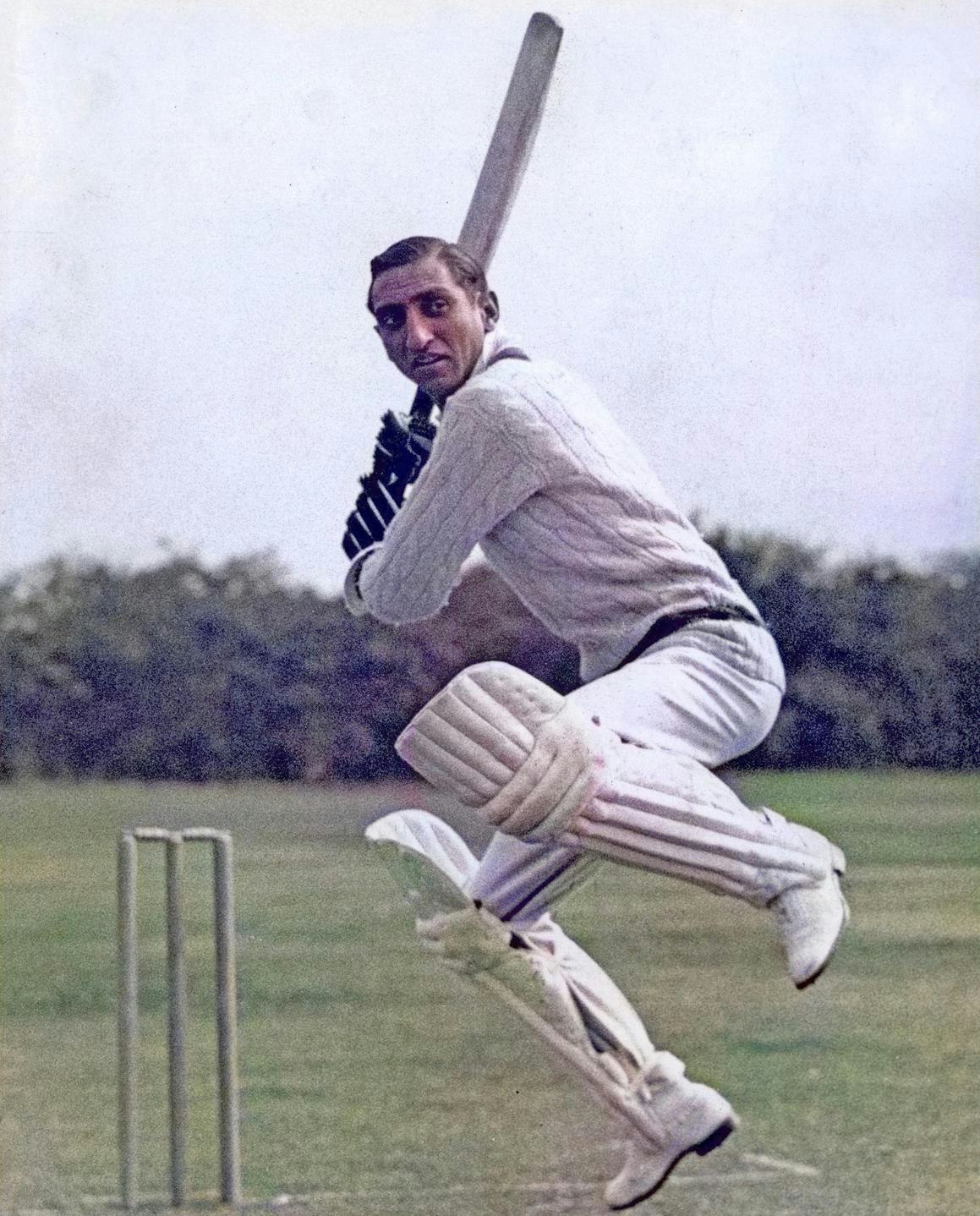

“Pat”, as he was known, made 106 and 84 against Cambridge in 1929 and an unbeaten 238 two years later, averaging 93 for the season. In three first-class matches in India that winter he made 77, 80 and 91. It was therefore surprising he was not in their squad to tour England, but Pataudi told the Board of Control he was unavailable. The suspicion was that he preferred to play for England.

The Maharaja of Porbandar was the tour captain, his princely status essential to the role, though Cricinfo notes that whilst keen on cricket “he was handicapped by being useless”. His two runs against Glamorgan were the highlight of his summer — it was remarked that he had more Rolls-Royces than runs — and he wisely let C.K. Nayudu lead the side in the sole Test, a heavy defeat. Pataudi, meanwhile, made 112, 72 and 165 in successive innings at Lord’s to earn selection for England’s Ashes tour.

They were led, ironically, by someone born in Bombay. Douglas Jardine was a ruthless leader, and the Ashes became notorious for his “bodyline” tactics designed to thwart Bradman with short-pitched bowling. Pataudi was selected for the first Test and made 102 but refused to join the bodyline field. “I see His Highness is a conscientious objector,” Jardine sniffed. He was dropped after the next Test.

Pataudi averaged almost 80 in 1934, earning him one more Test cap, and two years later was offered the captaincy of India on their second tour but withdrew on health grounds. They were led by the Maharajkumar of Vizianagram, who had similar cricketing ability to Porbandar but none of the self-awareness.

Vizzy effectively bought the captaincy, then fell out with half the team and allegedly offered one player a gold watch to run out a team-mate. He made 33 runs in three Tests but averaged 16 on tour. It was suggested that his generosity with gifts for opposing captains may have encouraged some full tosses and long-hops.

Pataudi finally led India on their third tour to England in 1946, but, whilst he averaged 47 against the counties, he struggled in the Tests. By the time they returned in 1952, he had died of a heart attack playing polo, aged 41. Ten years later, India would be captained by his son, Mansoor, the 9th and last Nawab, who was only 21 but regarded as the best fielder in the world and a fine batsman, despite losing an eye in a car accident.

“Tiger” Pataudi made eight centuries for Oxford and captained Sussex, but he felt no divided loyalties and led India in 40 Tests. Of all his feats, however, perhaps his proudest, or the most satisfying, came at Winchester in 1959 when he made 1,068 runs. It beat the school record set 40 years earlier by the Indian-born future England captain who snubbed his father: Douglas Jardine.