This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Two William Blakes vie for dominance. On the one hand, there’s the gently mystical Blake of England’s “green and pleasant land” — the Blake of the Women’s Institute, Tate Britain, illustrated tea towels and a London no higher than St Paul’s; a Blake concerned with “dark Satanic mills”, the abolition of slavery and the magic of exotic animals.

On the other, there’s a wild, hedonic, revolution-loving proto-hippie Blake, naked in his garden, touched by vital and romantic madness who exhorts his readers to tear down institutions, abolish authority and who (seemingly) justifies all manner of psychedelic and sexual experimentation; the Blake of the road of excess and the palace of wisdom, the doors of perception and desire; a mad, disinhibited and lusty Blake who would “sooner strangle an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires”.

In Awake! William Blake and the Power of the Imagination, Mark Vernon defends — convincingly — a third Blake. This is the Blake of the imagination, of re-enchantment, innocence, openness and of Christianity. Blake, Vernon writes, “spotted that Jesus’s greatest innovation was advocating an almost reckless belief in the forgiveness of sins, a virtue which is not found in pre-Christian philosophy”.

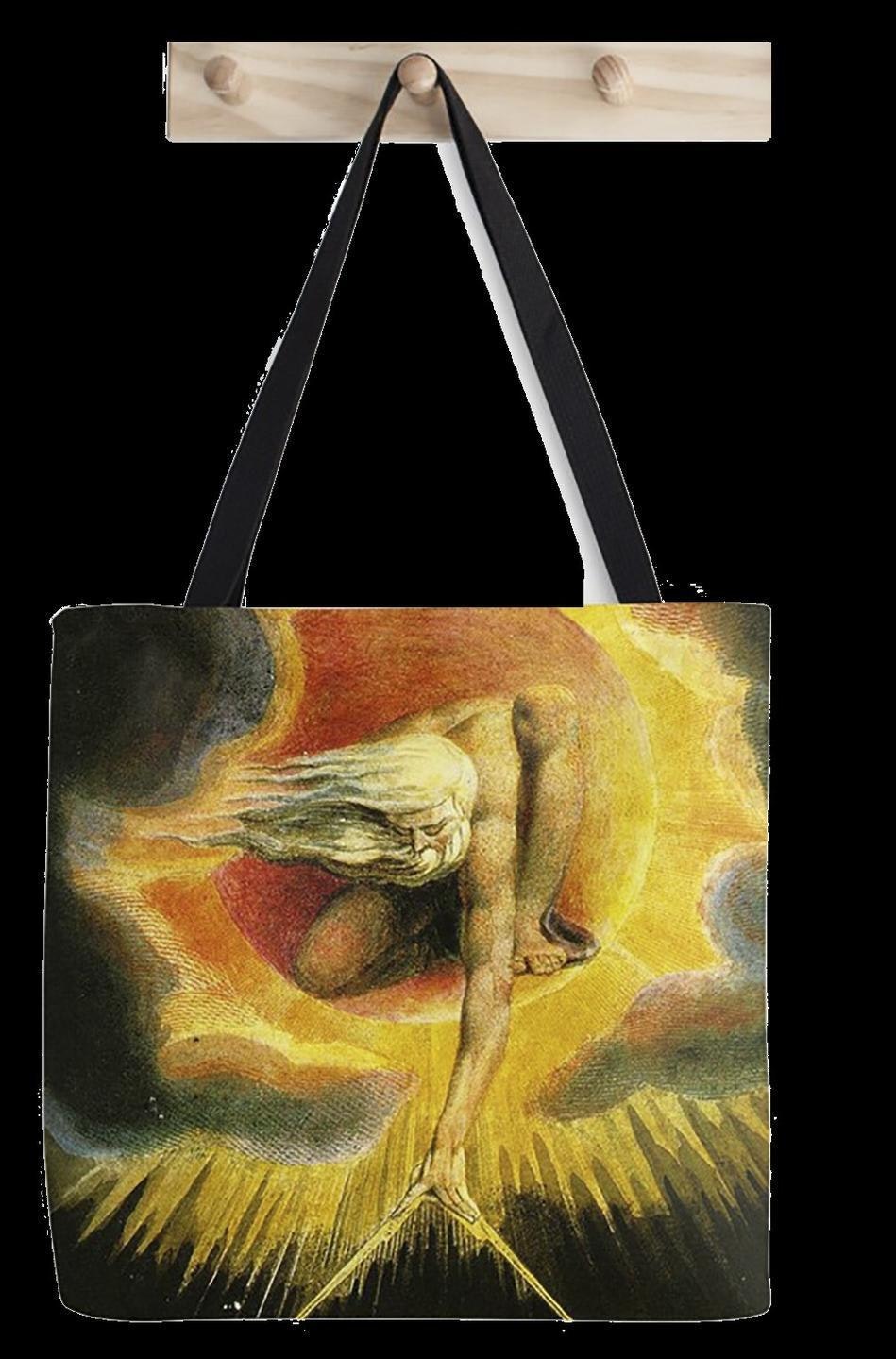

Blake’s heterodox Christianity was not that of the judgemental middle-classes (“Virtue is not opinion”) nor that of the Deists — Bacon, Newton, Locke — with whom he was to battle with all his life, perhaps not always fairly. Blake sought to oppose the dreary and imprisoning image of the God of reason via a “reexpanded imagination”. In Blake’s words: “The Imagination is not a State: it is the Human Existence itself.” Imagination is both infinite and eternal: it does not belong to us, exactly, rather we belong to it. All that we see is Vision.

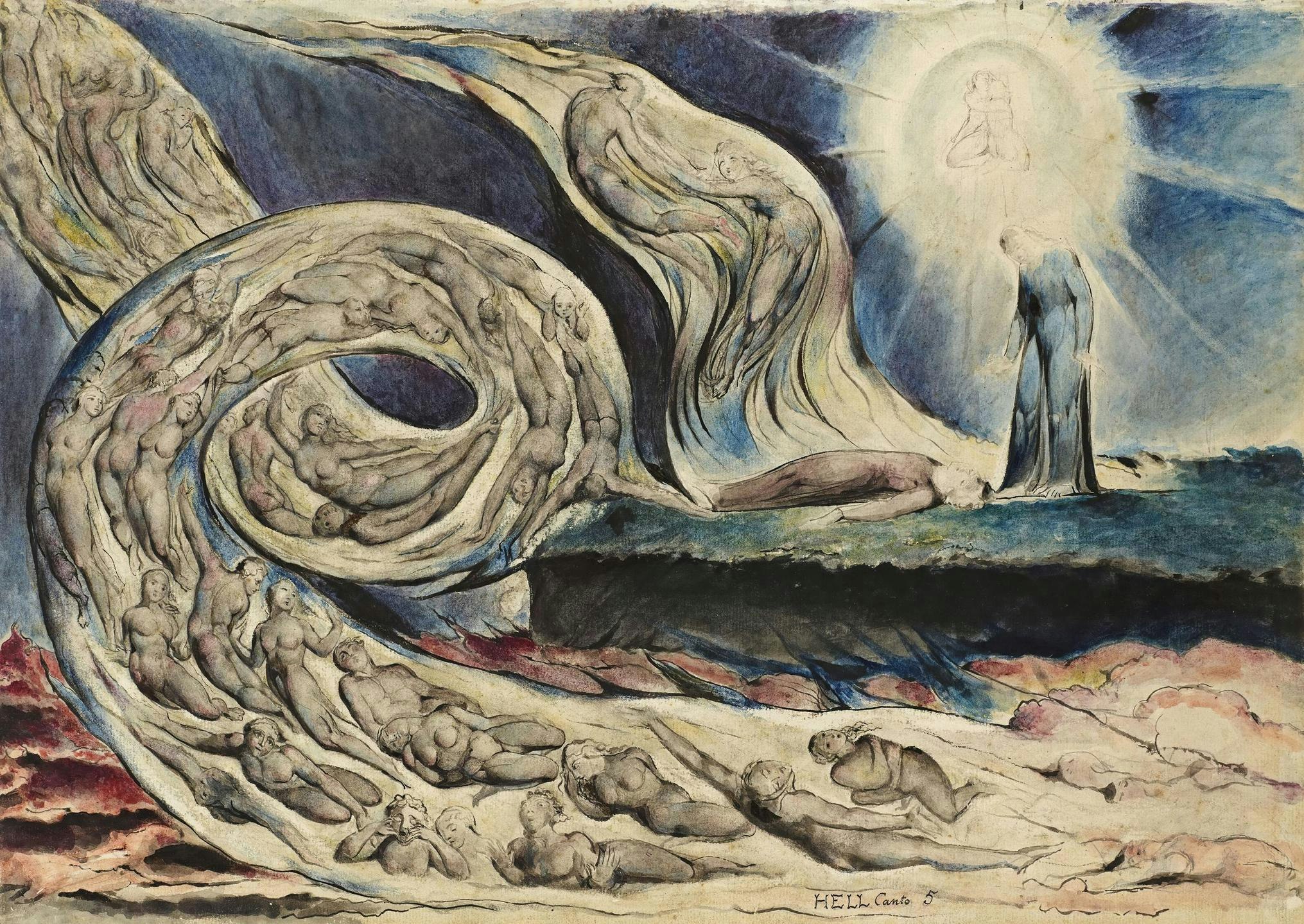

Vernon draws attention to the ways in which “contraries” for Blake produce revelation: “Opposition is true friendship”, after all. Vernon’s Blake is not trapped in obscure contradiction but rather struggling creatively with the tensions that arise between our human finitude and our relation to the infinite.

Vernon asks: “What if [Blake] were one of the sanest souls who can speak to us now, his work not an impenetrable puzzle but a catalyst for conversion?” Blake both recognises a way of life “shaped from top to bottom by science and technology” — unimaginably so today from a Blakean perspective — and instead embodies in his work and his life a “dramatically enhanced perception”.

Vernon’s background as an Anglican priest and a psychotherapist renders him a highly sensitive and sympathetic reader of Blake as a man, as a husband, as someone who had contact with and was aware of many of the great men of his time, artists and thinkers alike — amongst whom were Henry Fuseli, Sir Joshua Reynolds (“This Man was Hired to Depress Art,” wrote Blake), Thomas Paine (and Vernon tracks Blake’s disillusionment with revolutionary politics with care).

Vernon takes seriously Blake’s lifelong communication with angels, fairies and other entities, including the dead (but only one ghost). “My Fairy sat upon the table and dictated EUROPE,” Blake once said. Vernon addresses claims that Blake suffered from epilepsy or hyperphantasia, but concludes:

The desire that people have for Blake tells me something about his mind because straightforwardly disturbed people are never so engaging or ingeniously prolific … True generativity is marked by … a moving out into ever wider circles of insight, originality and delight.

Blake was, after all, productive, as we might say in today’s reductive language, and his loyal marriage to Catherine Boucher (greatly responsible for helping Blake realise projects, manager of the often precarious household finances and an artist in her own right) was admirable. Catherine would keep a guinea in reserve for when times were particularly tough and made it clear — using an empty plate as code — when Blake would have to make prints that actually sold.

Blake was not unreasonable or extreme, despite his idiosyncrasies and singularity:

He didn’t reject progress but progressivism, the ideology that was so demeaning: he did not want to resign his poetic genius, fearing spiritual depletion, but he never felt tainted by having to earn a living, as some of the Romantics who were to follow him did.

Vernon suggests that Blake’s perspective, always in development, was not so much antinomian (“simply chaotic”) but “transnomian”, that is to say “a state of being in transit and at least partially glad of difficulties and crises because they bring vital pivot points”. Vernon doesn’t entirely dispense with what we might call the hippie Blake, noting that sexual “affections and frenzies agitate a set of contraries with which we must wrestle if we want to live well”. He describes Blake’s attitude as a kind of “Christian tantra”: “[Blake] advocates not free love but large love.”

Awake! is an enormously appealing account of our most mystical of artists, mingling autobiography with the seriousness and initial opaqueness of some of Blake’s ideas and vision (not to mention the curiously named characters which comprise the Blakean mythos). By weaving quotations from Blake in italics throughout the book (an idea he takes from Joel Harrington’s book on Meister Eckhart), Vernon creates a smooth and intimate proximity to Blake that allows the “third thing” to shine through. He restores Blake to his rightful place as a Christian thinker: “The Christianity that Blake sought to revive is best felt not dogmatically described.”

Can Blake be rescued from “Blakeism”, both the tamed version and the New Age image? Vernon gives us the best possible account of how we might do this. We should revisit and take seriously, though not dogmatically, Blake’s insights and prophecies, his vision of Albion, his dramatic presentation of how imagination captures and transforms us.

After all, “For Blake, the apocalypse is not a calamity coming at some fearful moment in the future but is the moment-by-moment chance we have of discerning the path towards a fuller life.”