This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

“There’s something happenin’ here,” Stephen Stills sang in 1966, when some vaguely liberated folk in California began to decorate their hair with flowers. “What it is ain’t exactly clear.”

“For What It’s Worth” was the song, which still rings like a bell. “Stillsy” wrote some good ’uns when the mood took him; certainly a few more than David Crosby and Graham Nash, with whom he collaborated after leaving Buffalo Springfield.

But ain’t exactly clear? Oh, come come. It was clear as day even then. The young never need an invitation to frolic, and although the frolicking may have taken a vivid form in the Sixties, the impulse to prod one’s elders goes back to the Athens of Pericles.

“Counter-culture” became the phrase of choice. “Tuning in” and “dropping out” indicated a noble purpose. What it really amounted to was subsidised loafing, which ended when the flower children were told to settle their accounts. As many a cultural warrior observed when they begat children of their own, a conservative is only a liberal mugged by reality.

A friend who has done as much as anybody to improve the quality of London restaurants drank briefly from the well. Rowley grooved to The Grateful Dead and recalled the dressing-up ceremony before each concert, when everybody shed their daytime togs to don the robes of the tribe.

Then came prog rock, glam rock, heavy rock, disco and punk. Every group dressed to emphasise its uniqueness, revealing the while an inability to act with true freedom.

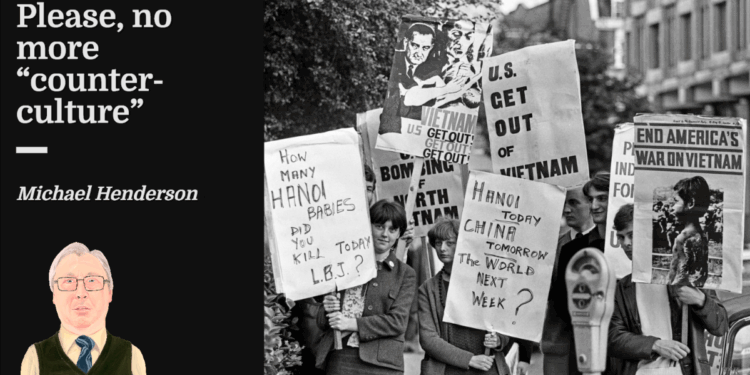

So “what happened to the counter-culture?” is not a question to detain the curious listener longer than a morning brew. Those young men and women grew up, is the answer. Yet Artworks on Radio 4 thought the subject merited five half-hour programmes. To nobody’s surprise it turned out to be a benefit for bores.

The presenter was Stewart Lee, a comedian who has spent the past three decades trying to detach the wit from halfwit. How clever he is! For all his talk of “the system”, though, and “the establishment”, it’s those like Lee who belong to the cosiest establishment of all, the one which assumes everybody outside the circle is an enemy of progress.

What a mishmash. The Beat poets, freeform jazzers, black militants, homosexual campaigners, new age travellers and striking miners were all lumped together, as though they marched under the same banner, when nothing could be further from the truth. Some of the most prominent actors, The Beatles for instance, were ambivalent.

What did Paul McCartney sing about in that summer of love? A lonely soul who lived on a hill, a tune your mother would know, a cheeky parking attendant, a childhood memory of Liverpool, and the joy of being 64. Bring on the revolution!

Lee’s commentary brought “vibrant scenes”, of course. And there were swipes at Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. But who voted for them? The people who had lived through the Sixties and been presented with the bill.

McCartney, like Mick Jagger and Roger Daltrey, is a knight of the realm. Eric Clapton casts his fisherman’s rod on the water. Steve Winwood, who played a fundraiser for Oz magazine in 1971, plays the organ at his local church. That, one might argue, is real rebellion.

We didn’t hear their voices. Instead, we got Capstan-strength crashers like John Harris and Andy Beckett from the Guardian, who described accidents to witnesses. This was shoddy stuff, lazily conceived and poorly executed.

Another Guardian journalist presented a Radio 4 two-parter about “the diminished authority” of the critic. Michael Rosen and Jonathan Freedland were unavailable, it seems, so the call went out to Arifa Akbar, the paper’s theatre reviewer.

According to Akbar the shift towards brayers on social media represents a new cultural democracy. The single voice matters less now that there are so many others out there bellowing wildly, whether or not they know anything. Gilbert and Sullivan sprang to mind: “when everybody is somebody, then no one’s anybody”.

She is wrong because the voice honed by experience is more necessary now than ever. Take Alex Ross, the New Yorker’s music critic. Like the much-missed Robert Hughes, that magnificent writer on art, Ross addresses the reader with a scholar’s touch. That is real accessibility.

Old-fashioned types brought up on what Akbar’s witnesses called “the legacy media” will recall the writers whose arrows pierced the target. A personal list might take in Rodney Milnes on opera, Charlie Spencer on theatre, Benny Green on the popular song, Craig Brown on books, John Preston on telly and AN Wilson on many things.

To borrow Ken Tynan’s observation about the critic’s function, those men knew the way without being able to drive the car. Judging by her palsied efforts, Arifa Akbar would struggle to find the clutch.