This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

Artists’ estates and lawsuits are never too far apart. Money, particularly when there is oodles of it, turns art and the control of art, febrile. In the case of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), the great American modernist who made the hardscrabble landscape of New Mexico her subject and her home, the scrapping started whilst she was still alive.

In 1978, O’Keeffe fired her long-time agent Doris Bry, the woman who had helped her run the estate of her former husband Joseph Stieglitz and who was executor of O’Keeffe’s own estate. The artist followed this up by suing Bry for the return of paintings and money she still held in her now ex-client’s name. The cause of the rift seems to have been O’Keeffe’s relationship with an up-and-coming potter named Juan Hamilton.

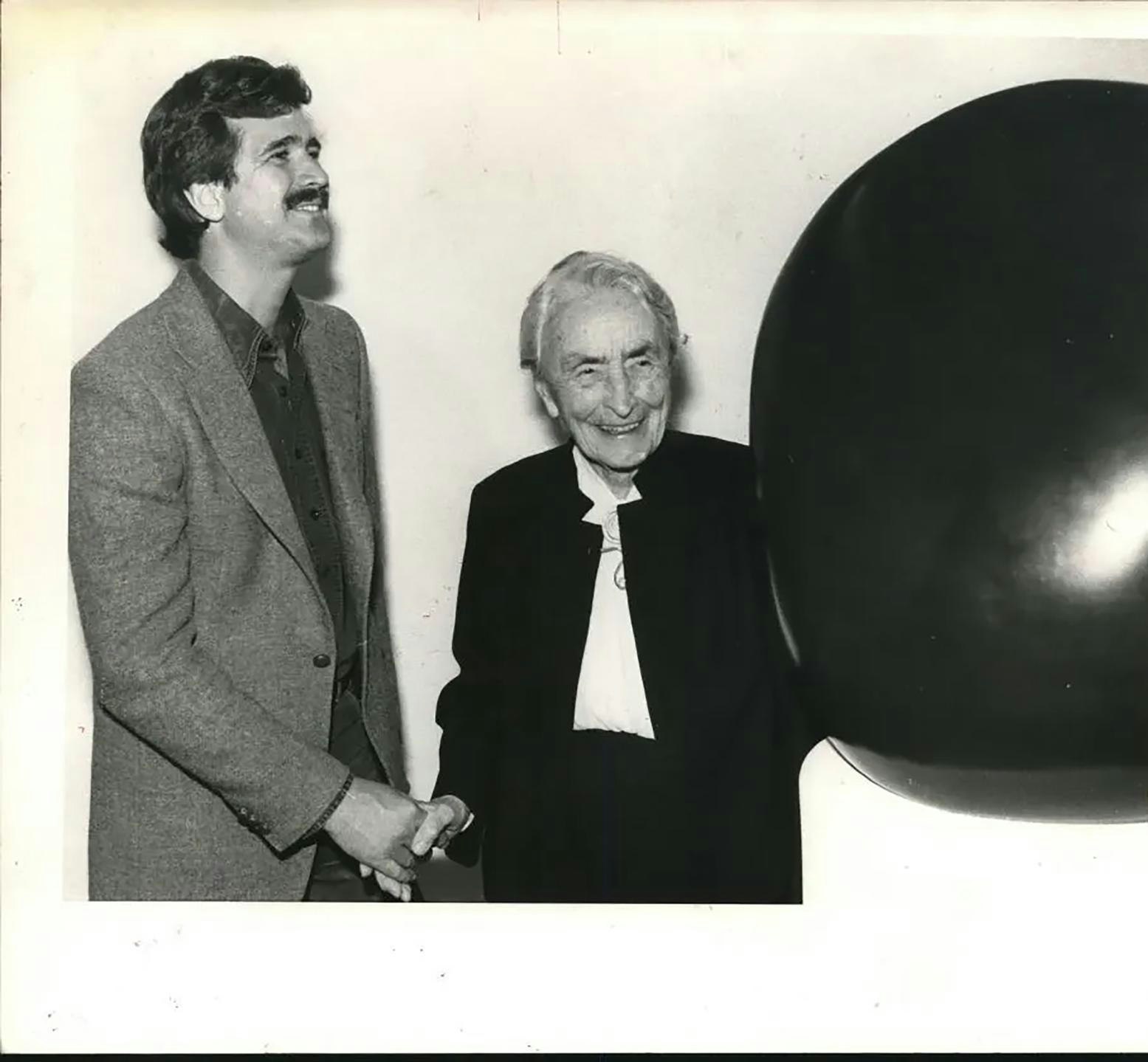

Hamilton, who died in February, stepped into the life of the widowed and childless O’Keeffe in 1973 when, after a speculative visit to Ghost Ranch, her home in the scrublands some 60 miles north of Santa Fe, the 86-year-old artist took the 27-year-old on as an all-purpose handyman. His first job for her was to straighten a jar of bent nails.

He quickly became indispensable, acting as chauffeur, secretary, painting packer, book editor, exhibition organiser and companion. She in turn encouraged him to develop himself as a potter.

The true nature of their relationship was never clear although there were rumours aplenty. “There is prejudice against us because she is an older woman,” Hamilton once told a magazine interviewer, “and I’m young and somewhat handsome.”

The association of her name was undoubtedly a help to him. In 1978 he held an exhibition of his pots at a gallery in New York; Joni Mitchell and Andy Warhol both attended this show by an unknown, and two of the pots were bought by the Museum of Modern Art.

The exhibition coincided with the sacking of Bry, and she retaliated by suing Hamilton for $13 million on the grounds of “malicious interference” between her and the painter. Two other legal cases quickly emerged and were settled. Hamilton would later be granted power of attorney over O’Keeffe’s estate.

For all the whisperings, the pair remained devoted. In 1980, Hamilton married — with O’Keeffe’s blessing — a woman who, like him, had turned up hoping to see the artist. As O’Keeffe’s health deteriorated, the Hamiltons looked after her at their own house, taking her to hospital, cutting up her food.

At her death in 1986, it emerged that in a codicil to her will, O’Keeffe had left Hamilton the bulk of her estate, comprising some $40 million worth of paintings and $50 million in property, transferred from the charitable institutions she had earlier intended to benefit.

O’Keeffe’s relatives took Hamilton to court, and he had to soak up the opprobrium thrown at him: “nothing but a tramp”, a “gigolo” driven by “greed”.

After almost a decade of legal wrangling, a settlement was reached in which Hamilton ceded much of his legacy but kept a cluster of paintings and watercolours, some property and assorted letters and ephemera. At the same time, a foundation was established to perpetuate O’Keeffe’s artistic influence.

Hamilton got on with his life. Nevertheless, as if in refutation of the claim that his interest in O’Keeffe was solely financial, he donated many pieces to the new O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe and held on to the rest for some three decades.

In 2020, however, in need of money, he sold 100 items for $17.2 million. He kept a few pieces back, including a painting that had inspired his pots, until his own death at 79.

If the fuss around O’Keeffe and Hamilton was primarily about money (with a side dish of prurience), a different dispute has arisen around the legacy of the Swedish spiritualist and abstract painter Hilma af Klint.

Little was known about af Klint (1862–1944) until the 1980s. She had left some 1,300 paintings to her nephew, stipulating that they should not be seen for 20 years after her death.

In the past few years, however, she has been swept up in the museum world’s drive to rehabilitate female artists and is now hailed as the woman who discovered abstraction before male peers such as Kandinsky and Malevich.

Despite the fact that she prohibited her work from ever being sold — her paintings were investigations into the spiritual realm and not “gallery art” — they do occasionally come to market, and the current auction record stands at $168,000.

A legal case has now broken out within the foundation that bears her name. The current chair, Hilma’s great-grandnephew Erik af Klint, argues that her work should remain guarded and accessible only to the “spiritual seekers” who understand her intentions. “When a religion ends up in a museum, it is dead,” he has said. His fellow trustees (all selected from the Anthroposophical Society) disagree, believing it their duty to spread Hilma’s renown.

The waters have been further muddied by the interjection of the dealer David Zwirner who has proposed an estate-management collaboration with the Foundation. Whilst Erik af Klint warns of a “hostile takeover”, Zwirner says the aim of a partnership would be “to further explore and celebrate af Klint’s groundbreaking contributions to modern art”. As things stand, both the direction of the foundation and the Zwirner initiative are in deadlock.

Perhaps what both the O’Keeffe and af Klint episodes demonstrate is that no one loves art as much as lawyers.