The Versatility of Tradition: An exhibition of work by Nigel Anderson

with an Introduction by Jeremy Musson

(Winchester: ADAM Architecture, 2025)

76 pp., many col. & b&w illus.

Having experienced in recent years such horrors as the rat-run of Penn Station, New York City, and Luchthaven Schiphol, Amsterdam, the calamitous dystopian ghastliness of Modernism in architecture needs no other examples to demonstrate its inhumanity, its seediness, its browbeating insensitivity, its cruelty, and its terrible, damaging impact on the human spirit. The monsters who create such environments should be recognised for what they are, and the puritanical, joyless, humourless, fundamentalist, self-referential cult of Modernism properly perceived as the enemy of humankind, of sensibility, of delight, of beauty, of tranquillity, and of everything that makes life worth living.

Some of us, however, have managed to resist the bullying cult, and have more and more absorbed the lessons of tradition in architectural design. We recognise that Modernism is really a stunt: it was based on a confusion of the functions of the architect and engineer, and on an impoverished, limited formula (supposedly the fulfilment of purpose in architecture) which excluded that æsthetic element that had been one of its essential qualities since the earliest dawn of civilisation. Moreover, owing to the deliberate neglect of the study of the past, the range of imagination and inventive ability in the supposedly “New Architecture” was extremely restricted: the fatal mistake was made of discouraging or even forbidding the study of any but contemporary architecture, so students were thrown headlong into things without any independent standard of judgement and with a wholly inadequate architectural vocabulary. Sir Reginald Blomfield (1856-1942) saw this state of affairs as similar to the plight of someone told to write a serious book with only the most rudimentary knowledge of the resources of the language to be used, and cited the concerns of the Classical scholar, John William Mackail (1859-1945), expressed in his celebrated lecture on Virgil: Mackail held that in times of rapid and chaotic change, it is essential to retain a standard of quality. That need is more pressing than ever today.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000) had no doubts where the fault lay in creating cities which were “the concretisation of the hare-brained ideas of criminal architects” … “without feelings or emotions, dictatorial, heartless, aggressive, flat, sterile, unadorned, cold and unromantic, anonymous and yawning emptiness”, all an “hallucination of functionality”: he laid the blame very firmly on doctrinaire Modernists. The Bauhaus mentality, he wrote, “destroyed the world we dwell in”, yet its “soulless dogma” was still taught in architectural schools, “against reason, beauty, nature”, and humankind. He pointed out that humans are “misused” for “perverse, dogmatic, educational, architectural experiments … Young architects who still have dreams of a more beautiful and better world in their heads” … get those dreams “taken away from them by force” or else they do not receive their qualifications. “Thus, only architects who have been brought into line become certified and so have the right to build.” He was to add that “today’s architecture is criminally sterile” and that the “architect as we know him today is only entitled to construct uninhabitable architecture”.

Indoctrination in architectural “education” starts with damaging a student’s self-esteem and confidence: humiliation is used, notably at “crits”, when anyone even hinting at the sensual possibilities of colour, ornament, surface-treatments, and forms, is criticised for committing “a criminal act”, because the deified prophet, “Le Corbusier” (1887-1965), had said that decoration was “of a sensorial and elementary order, as is colour, and is suited to simple races, peasants and savages … the peasant loves ornament and decorates his walls … decoration is the essential overplus, the quantum of the peasant”. So any suggestion of decoration, colour, ornament, or delight has to be eschewed: to conform with and accept without question Modernist positions became compulsory; feelings of guilt were sown in the minds of those who questioned such orthodoxy; and then solutions were offered to assuage that guilt. Those included prodding students to use alien forms and employ crude surfaces (like raw concrete, which ordinary members of the public hated, but adherents of the cult claimed to insist was “honest” and “true”, and therefore somehow “pure”, “untainted”, and “moral”), and of course “study” (i.e. look at the pictures of) buildings by Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies (1886-1969), and other dodgy deities acceptable to the cult. Today, generations of Modernists that rose to prominence from the 1920s are being eclipsed by later fashionable figures, all of whom claim to be Modernists taking the approved anti-Historicist line. Attending a “crit” nowadays can be as alarmingly dispiriting as it ever was, for projects far too often seem to have no connection with the real world at all: context, people, places, and scale are all ignored as students retreat into fantasies where distorted forms are de rigueur and spider-webs of mechanically-drawn lines serve to create a pea-souper of a fog that hides the uncomfortable fact that the visuals are there to conceal an absence of thought.

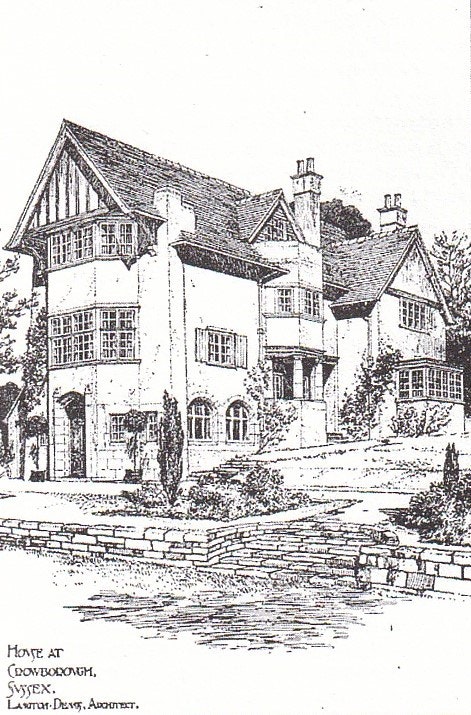

Nigel Anderson has been one of the leading figures in traditional architecture in Britain, having joined the Winchester practice that is now ADAM Architecture in 1988, becoming a Director in 1991, and has only recently retired. Despite having studied at that bastion of Modernist orthodoxy, the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, Anderson had already acquired a love for the decent domestic architecture to be found on the Kent-Surrey border, but a major influence was the gift from his grandmother of her father’s sketchbooks from the 1870s and 1880s depicting many examples of southern English traditional vernacular buildings as well as containing designs for furniture and metalwork artefacts. The author of those sketchbooks, Anderson’s great-grandfather, was the architect Langton Dennis (1865-1945), who had been a pupil (1882-6) of Sir Ernest George (1839-1922) and Harold Peto (1854-1933), and had worked (1887-8) as an assistant to Thomas Edward Collcutt (1840-1924), all very distinguished architects. While with George & Peto he worked with Edward Guy Dawber (1861-1938), who was to be knighted in 1936, and who became an authority on the vernacular architecture of Kent, Sussex, and the Cotswolds. When Dennis was elected as an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1889 he was supported by George, Collcutt, and Richard Phené Spiers (1838-1916), all men of considerable standing in what was once a sane architectural world. Some of Dennis’s finest houses were in and near Crowborough, in East Sussex: they included Forest House, Aviemore Road (1903), Warren Hill (1906-7), for E.L. Lynden-Bell, and Windlesham (1907-8), for Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (1859-1930).

At UCL, Anderson was subjected to the usual enforced diet of Corbusier-worship: at the time, he thought that “designing” in that mode was “like being asked to write in a foreign language with little or no knowledge of its vocabulary, grammar, and syntax”, but he discovered the interesting “butterfly” plans of architects such as Richard Norman Shaw (1831-1912), Edwin Landseer Lutyens (1869-1944), Detmar Jellings Blow (1867-1939), and Edward Schroeder Prior (1852-1932). The celebrated exhibition of the work of Lutyens at the Hayward Gallery in 1981 was a revelation, helping Anderson and some of his contemporaries to rebel against the stultifying tyranny of the Modern Movement, although not all the “tutors” in Modernist indoctrination techniques were happy about such apostasy: one, James Gowan (1923-2015), likened such explorations to copulating with corpses, a typically vehement reaction by those fundamentalist Believers in the deified monsters who have created Hell on earth. However, it became apparent to Anderson and some of his fellow-students at the time that not only did traditional and Classical languages of architecture each possess a “vocabulary, grammar, and syntax”, but were very much alive and well and capable of continuing development and application. The rancid, poverty-stricken emptiness of Modernism rendered it rather more dead in comparison.

Given his true instincts and developing interest in the works of great architects of the past, it is rather surprising that Anderson gained early work experience in the office of Colonel Richard (Robin, originally Rubin) Seifert (1910-2001), one of the largest practices of the time, responsible for the tower-block called Centre Point, at the junction of Tottenham Court Road and New Oxford Street, London (1959-66), of which Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-83) observed it was “coarse in the extreme” and asked “who would want such a building as its image?” Eventually, however, his professional path led him to Winchester in 1988, and a fruitful career with Robert Adam (b.1948) and his colleagues.

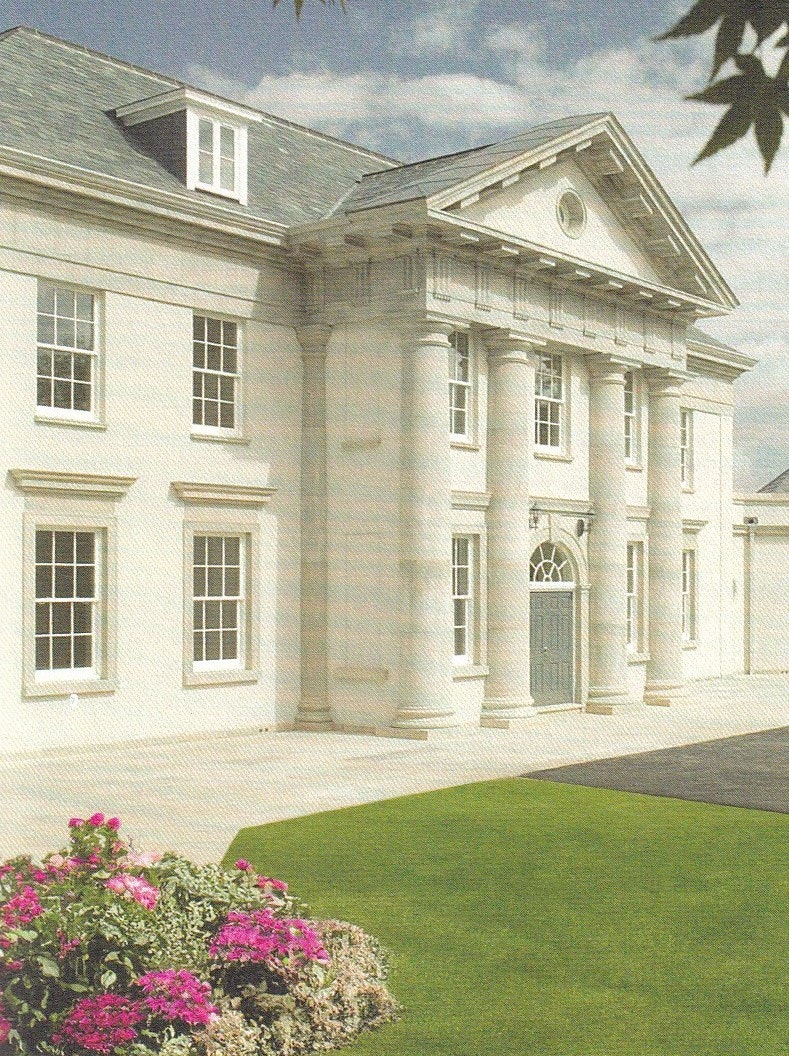

Anderson’s retirement after 37 years has been generously marked by an exhibition of his work, organised by his friends and fellow-directors at ADAM Architecture, Hugh Petter, George Saumarez Smith, Robbie Kerr, Darren Price, and Robert Cox, and a splendid catalogue of this (with an Introduction by Jeremy Musson) is available in digital format, although a few copies were printed, and I am fortunate in having one of those. The work illustrated is of very high quality, and includes the fine Ingliston House in the Palladian style at West Drive, on the Wentworth Estate, Surrey, of 2004. A contrasting work, yet one of equal refinement, is Eastridge House, Binley, Hampshire, of 2000, with delicate Gothick glazing-bars, carved decorative bargeboards, canted bays, hood-moulds, and other features suggestive of influences from the Regency cottage orné.

At a new villa, Southover, in East Sussex (2001), Palladianism merged with the Arts-and-Crafts “butterfly” plan, and that plan-form was used again at an ingeniously designed house at Homington in Wiltshire (2006) which features facings of Chilmark limestone and knapped-flint bands and panels, and has a curiously, though very subtle, Italianate air about it.

This gifted architect was also active at Poundbury, in Dorset, the much-maligned and ridiculed project of His Majesty the King when Prince of Wales, in the genesis of which the late, great Léon Krier (1946-2025) was intimately involved, to screeches of rage from the architectural Establishment. Criticism is now rather more muted, as the success of the project becomes ever more clear.

Anderson has observed of his relationship with the Duchy of Cornwall that he and his team were “given the luxury of time to really explore and analyse the local building forms and traditional construction techniques of individual buildings, the spaces between them and their boundary treatments as well as the layout and spatial characteristics of the local villages and towns … These all served to inform and influence” the development designs along with the “compilation of pattern-books and basic master-plan codes that would form part of the agreement between the Duchy as landowner and the chosen development companies” thought best suited to take the schemes forward. In that respect, the reference to pattern-books is very interesting, for the existence of such things in the 18th and early 19th centuries ensured that even modestly talented architects could produce perfectly acceptable and humane work that did not jar, but fitted in courteously with existing fabric, something ill-mannered Modernists, with their insolence and loutish interventions, could never achieve.

And it was not just new work which interested Anderson, for his involvement with historic buildings required scholarship, sensitivity, and care so as not to damage what was often fragile. An excellent example of his work can be found at what was a former rectory at Kimpton in Hampshire, a timber-framed structure of 1444-5 with a jettied upper floor and close studding below the jetty of c.1535, the date perhaps of the “showy south wall of red brick and render in a chequerboard pattern”, as The Buildings of England volume on Hampshire: Winchester and the North puts it. The same tome records that the mullioned-and-transomed windows of what is now known as Kimpton Manor were restored in 2003-4, and the ground-floor oriel was reconstructed from evidence of what had been inserted in 1560. Other works include tactful additions to existing buildings, especially in Hampshire, all executed with particular regard to materials and how they are used.

In 2007-11, Anderson played a major part in the award-winning restoration and conversion of the Grade II* Bentley Priory, set in registered parkland near Stanmore, a former monastic site on Harrow Weald. John Soane (1753-1837) had carried out distinguished alterations and additions for John James Hamilton (1756-1814 — 9th Earl [from 1789] and 1st Marquess of Abercorn [from 1790]) in 1788-98, and further enlargements (c.1809-10) were made under William Wilkins (1778-1839) and (1815-18) Robert Smirke (1780-1867). Queen Adelaide, consort of King William IV (r.1830-7), died there in 1849. In 1852 the estate was acquired by John Kelk (1816-86 — 1st Baronet from 1874), the eminent Victorian building contractor, among whose distinguished works in London were All Saints church, Margaret Street (1849-59 — designed by William Butterfield [1814-1900]), and the Albert Memorial (1862-72 — designed by George Gilbert “Great” Scott [1811-78 — knighted in 1872]). Kelk greatly extended the building, giving it a pronounced Italianate flavour, employing John Johnson (1807-78) as his architect, and later, from 1885 the ensemble was converted into an hotel for Frederick Gordon (1835-1904), known as “The Napoleon of the Hotel World”, but it was not a success, and in 1902 became a school. In 1926 it was acquired by the RAF, and during the Battle of Britain it was the HQ of Fighter Command. A severe fire destroyed part of the interior in 1979, but much was recreated in facsimile. Anderson’s commission was to restore the fabric, convert part of the house into a museum, form eight spacious apartments in the rest, working with Giles Quarme & Associates, and design a further 95 residential units on the sites of former RAF structures, all in a simplified Soanesque style responding to the main mansion block.

Anderson has not adopted any rigid doctrinaire attitudes to design, for the stylistic range of his work is wide and eclectic, sometimes firmly Classical, but at others responding to Arts-and-Crafts values, to local traditions in building, and to a Regency architecture that often was inspired by the Picturesque. Another powerful influence on his work has been the Queen Anne style, which he himself has acknowledged as “quintessentially English”. As Musson writes in his sensitive Introduction, his work “is a celebration of enduring values, of good sense in architectural design, of good proportion, and fine local materials. Above all, one senses a profound respect for the past, for the sheer versatility of tradition, and a great joy in the now”.

Quite so, and I salute a humane being who has been a key figure in one of the world’s most significant practices in traditional architecture, and who has made an enormous contribution to its continuing evolution as a civilised art, creating beautiful environments that nourish rather than destroy the human spirit.