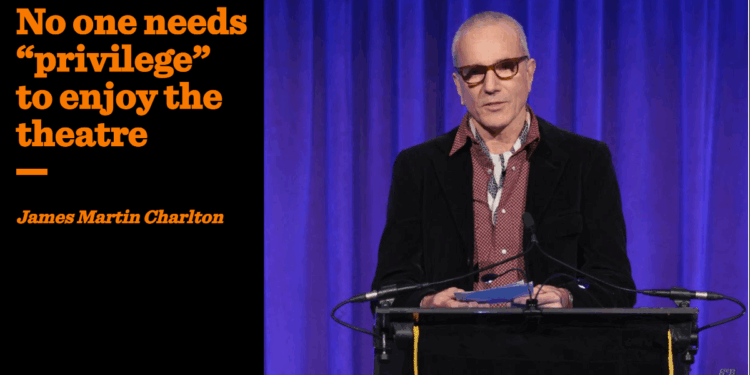

Why Daniel Day-Lewis is wrong to think the working class need permission to go to the theatre

Daniel Day-Lewis has returned from his latest Sinatra-like retirement with a new movie, the critically excoriated Anemone, and has condescended to be interviewed at BFI Southbank. Alongside disavowing his previous statements about leaving the business, he defends method acting, admits to being bothered by his film’s reception, and offers some intriguing remarks about British actor training and what he calls the elitism of theatre.

Some of his complaints are fair enough. West End ticket prices have risen exponentially. Carl Woodward has highlighted how audiences are being priced out. Yet what truly struck me were Day-Lewis’s comments about theatre and elitism. He rails against the assumption that the stage is superior to the screen. He recalls that during his training (1975–78), the emphasis was almost entirely on live performance.

He then makes an irritating claim. Theatre, he states, is an exclusive cultural institution which “essentially relies on people having had the privilege of an education that allows them to believe that they’re entitled to go to the theatre … It’s a relatively small group of people that is available to, and that is just quite wrong.”

Full disclosure: I have considerable skin in this game. I hail from a working-class family in Romford, growing up there in the 1970s on a council estate. At no point can I ever recall thinking that I was not “entitled” to go to the theatre. Probably because, from a very early age, my parents — both of whom worked on the production line in Ford car factories — took me to theatres. At five, I was treated to pantomime at the London Palladium. A couple of years later, I saw Carry On London (I still can’t quite believe I saw Sid James live). By the mid-70s, I was being taken to our local, the Queen’s in Hornchurch, to see the likes of Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer and Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (back in the day it bore a now-unpublishable title). Theatre-going was as natural to us as cinema-going, albeit a little less often as it was further away than the local Odeon and somewhat more expensive.

But perhaps Day-Lewis was referring not to popular stage entertainments but to the legitimate theatre? It’s this, apparently, that the plebs cannot appreciate without an education as expensive as his own, at Sevenoaks School. The antics of Tony Lumpkin in She Stoops… were making this state-school pupil laugh uproariously at ten. I admit I harboured a preconception that Shakespeare might be unintelligible before I saw any, but when taken by our comprehensive school to Twelfth Night (a wonderful RSC production starring recently deceased John Woodvine, hilarious as Malvolio), my classmates and I could easily follow what was happening. If there were words or phrases that we did not understand (what exactly is a “bum-baily”?), we weren’t such divs that we couldn’t look them up later.

Back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, there were various local government schemes that allowed schoolchildren in the Greater London area free tickets for institutions such as the RSC and the National. Through these, we were taken to see such heavyweights as Shaw, Brecht, Sheridan and Büchner. Some of the class found them boring, but many of us enjoyed and avidly discussed them. We did not need long lessons in how to approach them. At the same time, we were going to see films like Monty Python’s Life of Brian and Scum at the cinema, and watching Play for Today on television. Smart state school kids seek out work which stimulates them. We don’t need tens of thousands spent on elite education to help plays “make sense.” We just need access to them.

Some may harbour preconceptions that classical theatre will be difficult, but once that hurdle is passed, we happily go

State school-educated people do not, in my experience, feel intimidated about going anywhere simply because we do not feel entitled. Some may harbour preconceptions that classical theatre will be difficult, but once that hurdle is passed, we happily go. Those school visits gave me a taste, so I badgered my by-now widowed mum into taking me to classics and contemporary drama. She enjoyed Shakespeare’s comedies and developed a fondness for Alan Ayckbourn and Harold Pinter. Our tastes could diverge — she was of a generation that didn’t appreciate what used to be called “bad language,” and we almost fell out when Howard Barker’s Victory: Choices in Reaction at the Royal Court had the cast drop the c-word nine times in its first five minutes. But these are matters of judgment, not questions of comprehension. We both knew what the word meant.

State school alumni go to the theatre when the fare appeals to them. Years later, a lot of people from my home town in Romford made the trip to the South Bank to see local lad David Eldridge’s play about the place, Market Boy. It may be that many working-class, non-privately educated people don’t go to the theatre because what’s on offer is simply uninteresting. What’s appealing about yet another play on adultery and angst among the monied classes? Or the prospect of being lectured by a writer attempting to drum leftish shibboleths into the audience? I sympathise. Only last week, my trip to see Hugh Whitemore’s Alan Turing play Breaking the Code was impaired by a new epilogue by Neil Bartlett, appended in case the audience were too dim-witted to grasp that the protagonist was an “LGBTQ+” martyr.

The glamour of celebrity may be attractive to actors in training, who harbour (as Day-Lewis clearly did) dreams of screen stardom. Yet attitudes like Day-Lewis’s contribute to the erosion of Britain’s stage-acting traditions. Many drama schools now teach screen acting. We hear complaints that the verse speaking one hears at the RSC these days is hardly comparable to that of John Woodvine’s generation. Michelle Terry, the artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe, has warned that drama schools are no longer equipping students to speak classical verse. The issue, then, is precisely the opposite of the one Day-Lewis posits. Must we discard our theatrical tradition, simply to indulge a wealthy man who cannot in any case decide whether or not he wants to make films – and who walked out of playing Hamlet because he thought he saw his own father’s ghost?

Day-Lewis’s father was, of course, the Poet Laureate Cecil Day-Lewis, and his maternal grandfather was the film mogul Michael Balcon. All of this makes him rather less than qualified to pontificate about what those of us without a public-school education can or cannot understand. The culture of low expectations for “underprivileged” kids runs riot through the public-school custodians of our arts and media. Soon after my play Fat Souls won a competition at the lamentably lost Warehouse Theatre in Croydon, I attended a panel discussion there on new writing. The representative from the BBC told of his fight to produce “quality drama” and announced, “of course, we have to produce EastEnders for the tower blocks.” Ladies and gentlemen, I longed for quality drama, loathed EastEnders, and was living in a council tower block at the time. I will leave the reader to imagine what went through my mind on hearing that gross generalisation — similarly unprintable thoughts strike me on reading Day-Lewis’s cant.