At a prison just outside Milton Keynes, in a silent chapel, in a small circle of chairs, Nick Dawson sat beside his wife and waited to meet the man who had tortured and murdered his identical twin, Simon. This man, along with one other, had kicked and beaten 30-year-old Simon until he was unconscious. They removed his watch, stole his bank card, revived him enough to learn his PIN, then threw him into a pond to drown.

For 16 years, Nick had viewed these murderers, Craig Roberts and Carl Harrison, as sub-human – evil monsters. He had fantasised about torturing and killing them. Now he was going to talk calmly, face to face with Roberts, the apparent ringleader of the two, and Nick felt terrified. Was he being disloyal to his twin? ‘Deep down, I knew it was the right thing to do,’ he says. ‘There was something driving me on.’

A decade on from that prison meeting, Nick’s new book Face To Face tells the full story of this extraordinary encounter and the life-changing power of restorative justice. The book is also a harrowing account of a murder and its impact on a family.

From the outside Nick, now 56, has an enviable life. He and his wife Jules have both taken early retirement after long careers with BP and share a beautiful house in Surrey. Their two adult children have left home and are doing well. But the murder of his twin in August 1998 has tainted every moment of the years that followed. ‘For me, you don’t get “closure”,’ he says. ‘It’s a life journey.’

Nick (right) and Simon, aged seven

Nick and Simon had shared an idyllic childhood in Cumbria. Their father worked as a sales and marketing director for a local company and Nick spent his early years cycling, camping and adventuring with his brother Richard, who was almost three years older, and his twin Simon, born ten minutes apart. They were known simply as ‘the twins’.

‘In the early years it was virtually impossible to tell us apart,’ says Nick. ‘Only our mum and a few close friends could do it – even teachers called us “twin one” and “twin two”. We were both quite shy children, and we had the same interests. We were a pair, we were almost one – two halves making up a whole. It’s lovely being a twin – having that life partner and companionship. You protect each other. You have this empathy and connection. You finish each other’s sentences.’

As they grew older, inevitably, they’d followed their own paths. ‘I was the more serious one, a bit more focused on my studies, and Simon was more maverick, a bit wilder, terrible with money.’ By 29, Nick had married and settled in Surrey as a chemist for BP. Simon, a computer programmer, was based in Birkenhead, Merseyside. He was highly sociable, popular, living the single life. Still, the brothers stayed close. Three weeks before Simon’s death, they met halfway, near Oxford, to celebrate their 30th birthdays.

At the end of that month, Nick and Jules were camping in Cumbria for the August bank holiday – Nick was showing his wife of six months his childhood stomping ground – when his father called. ‘He just said those words, “Simon’s been murdered”,’ says Nick. ‘My immediate response was to cry and shout out. It was total anger and disbelief. I didn’t even ask any questions.’

Simon had gone for a night out in Bromborough, an area he didn’t know well, and was meant to be staying with a friend nearby. Somehow, he’d become separated from his friends at the nightclub and lost his way back. His badly beaten body had been found in a nearby pond early the next morning. It later emerged that, worse for wear after a few drinks, Simon had innocently asked passers-by, Craig Roberts, 16, and Carl Harrison, 19, for directions to his friend’s house. The teenagers had a long list of offences behind them – Roberts had been released from a Young Offender Institution that very morning. They offered to show Simon the way, led him into a park, then robbed and murdered him.

‘My dad always said that two young lads “tortured and executed” his son,’ says Nick. His book contains many haunting images from the days after Simon’s murder. His father howling in the garden and wandering the streets at night. His mother shutting herself in Simon’s wardrobe, burying herself in his clothes. His visit to Simon’s cut and bruised body for one last time in the mortuary, kissing him goodbye.

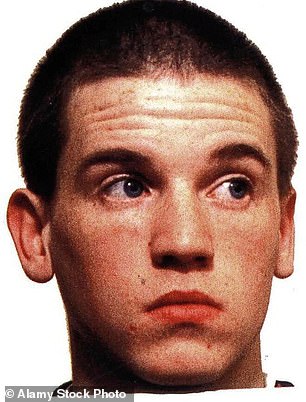

Teenagers Craig Roberts and Carl Harrison were found guilty of Simon’s murder

The arrests were relatively quick, and a year later Roberts and Harrison were found guilty of murder. Nick was there for the trial – looking identical to their victim. ‘They didn’t want to look at me,’ he says. ‘They were trying to put on a brave face for their family. They were a little bit blasé; occasionally they would smirk.

‘I felt utter hatred towards them. I scared myself by how angry I felt. We experienced huge relief with the verdict. Now we needed to get on with our lives.’

But how could they? It was as if part of Nick had died with his twin. At night, the loss invaded his dreams. By day, he was haunted by visions of horror. Out driving, suddenly, to him, the windscreen would be covered with blood. Nick clung to his parents and they to him. ‘For them, I was a living version of Simon and they could not let me go,’ he says. ‘Poor Jules. Sometimes I look back and think, “How did our marriage survive?’’’ Years passed, they had two children, lived in America for a while and found a way forward – but time certainly didn’t ‘heal’.

The first step towards restorative justice was in 2012 when Simon’s killers came up for parole. As part of the process, the family was invited to read victim impact statements at the prison parole hearing. ‘There’s no dialogue. You’re only allowed to go in separately, read your statement and leave – but it was incredibly powerful,’ says Nick. ‘Both [murderers] Craig and Carl were very emotional. I still remember Craig, holding a tissue, tears running down his face while I spoke about Simon. In that moment he turned from a monster to a human and, bizarrely, I felt sorry for him. I couldn’t believe that feeling. As I walked out I felt, “I need to talk to you.”’

Parole was not granted, and Nick began exploring the possibility of meeting Roberts through a restorative justice programme. Incredibly, Roberts was doing exactly the same and Nick received his request. (Nick’s parents and brother were supportive but chose not to be involved. Harrison had not made a request to take part in the programme either.) In March 2015, after much preparation, the meeting went ahead in HMP Woodhill. At the trial, Roberts had been a small smirking kid, but now, flanked by prison guards, he was a strong, grown man. ‘He’s very fit, a bodybuilder and he had this broad Scouse accent,’ says Nick. ‘I don’t know why, but hearing his voice was a shock.’ They didn’t shake hands. ‘I’d already decided that wouldn’t happen. It felt like an acknowledgement I wasn’t ready to give.’

The facilitator suggested they start with Roberts relaying the events of that night. ‘He talked about his release from prison that morning and Carl meeting him at the prison gates,’ says Nick. ‘They went straight to the pub.’ By the time they came across Simon hours later, they were drunk and high and had driven to Bromborough in a stolen car. Nick wanted every detail about Simon’s murder. Did Roberts stamp on him with both feet or just one? Did Simon cry? What were his last words? ‘Some people would probably never want to know those things, but I crave this connection with Simon,’ he says. ‘I wanted to bring him alive even in the last moment of his life.

‘Craig was remarkably honest and keen to help. At first, he struggled and couldn’t look at me but when he realised I wanted to know, he opened up.’

Nick, pictured in 2018, laying flowers at the pond where his twin’s body was found in 1998.

Nick also asked Roberts about his own upbringing. His father had been in prison, and he had been in foster care at ten. By 16 he was an angry career criminal. ‘He told me that his dad had taught him violence was the only way to earn respect,’ says Nick. ‘He’d been beaten by his stepfather, abused in the foster home. It’s not an excuse but if he’d had a stable, loving childhood it probably wouldn’t have happened.’ Roberts told Nick that, at the start of his sentence, he was desensitised, caught in his own self-centred world. He viewed the murder as just an ‘incident in his life’. Over the years though, with therapy and education, he gradually realised the enormity of what he’d done. He had killed someone. He went on to take nine GCSEs and an English literature A level in prison. He wrote poetry and asked if Nick would like to see it. ‘I still have his poems and what was clear is that he’s an incredibly deep thinker,’ says Nick.

‘He said, “I struggle with how I can apologise to you because what I did to your family was so evil, the word ‘sorry’ is hollow. I want my actions coming out of prison to be my apology – my commitment to being a better person and never coming back.”’

They were together for almost four hours. By the end, Nick was exhausted, elated, emotional – and his life had changed. ‘To hear Craig’s shame and regret directly from him moved me towards my own definition of forgiveness. For me, forgiveness is ongoing. But it helped me understand what happened, accept it and live at peace.’ Four years later, when Roberts’ next parole hearing came round, Nick attended and read a new victim impact statement. ‘I said, “You’re ready to come out now. You deserve a second chance. I just want you to promise that you’re not going to return to prison.” Once I’d wanted to torture him to death. Now I was almost wishing him all the best. I had seen him as a human being.’

Roberts was released – and has not returned to prison. Harrison was released earlier, in 2017, but was returned to prison for breaking licence conditions – Nick isn’t fully aware of the reasons why. His next parole meeting is in July. ‘I’ve prepared my statement, which effectively says, “Please take this chance and make the most of your life,”’ he says.

A passionate advocate of restorative justice, Nick volunteers and gives talks in prisons. He regularly returns to Brotherton Park, where the murder took place. It’s a beautiful spot. ‘I feel Simon’s spirit there,’ says Nick. ‘I’ve walked that park for 27 years and I still want to know where he was attacked, the route they took him. When Simon’s body was found, his shoe was missing and I’m still looking for it. I was there a couple of weeks ago with our dog, but we didn’t find it.’

Part of him will always be on a quest. ‘I spend a lot of my life trying to understand more and find meaning in this whole thing and I don’t think I’ll ever stop,’ he says. ‘But meeting Craig helped me become normal again. There’s always damage there, but it righted some wrongs, it helped heal some hurts. It helped me repair.’

Face To Face by Nick Dawson will be published on 3 July by Icon, £16.99. To order a copy for £16.14 until 13 July, go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937. Free UKP&P on orders over £25.