My decision to leave the party I’ve served for more than 30 years is possibly the most difficult I’ve ever had to make, and it has taken me 12 agonising months to reach.

It was shortly after the last election that I was discussing the catastrophic failure of the Conservatives with a former Party donor.

‘If only the Conservative Party had behaved more like Conservatives when we were in power, we wouldn’t be in this mess,’ he told me despairingly.

The penny dropped. I realised at that moment that my political principles have never altered.

My core beliefs are the same today as they were the day I joined the Conservatives back in 1995.

It was the Conservative Party that had changed, not me.

Today, to my friends in my former party I would say this: as we teeter on the precipice of terminal economic and social decline, you don’t have the luxury of time to stand stupefied, wondering what went wrong and thinking about how to put it right sometime in the future.

Nor do you have time to hope that your Party will one day wake up, get its act together and unite to rid us of a Labour Government that is driving our country into the ground.

For me and others who lived through Labour’s tenure in the 1970s, we know how this story ends.

‘My decision to leave the party I’ve served for more than 30 years is possibly the most difficult I’ve ever had to make, and it has taken me 12 agonising months to reach,’ writes Nadine Dorries

Nadine served as the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport from September 15, 2021 to September 6, 2022

My political journey began in Liverpool. I was born in 1957, in Breck Road, Anfield, one of the most economically and socially deprived wards in the country.

Those black and white Picture Post photographs you occasionally see of children in the Sixties, grubby and urchin-like, playing on bombed-out waste land – well, that was me. I was one of those kids.

Politics informed every aspect of my life from my earliest days. As a child, I would lie on the rug in front of the fire in our rented terraced house, the fabric of which still bore the scars inflicted by Luftwaffe in the May Blitz and drift off to sleep as the assembled adults engaged in passionate conversations about the issues of the day.

Liverpool had a vibrant political scene, firebrand politicians and, with a population that included many of Irish heritage, there were divisive sectarian loyalties, too. I remember the annual Orange Lodge marches that paraded past our front door and the IRA bomb scares in the city during the Sixties.

I recall the poverty, too. My father, a bus driver, suffered from Raynaud’s disease, an agonising circulatory disorder that led to the amputation of his toes. It limited his ability to work.

There were many times when I would be dragged under the kitchen sink to hide from the rent man as he banged on the front door or peered in through the window. And I’ll never forget our kindly neighbour – she only recently passed away – who once loaned me shoes to wear to school.

I try to remember happy times, of course. But the lack of money, the ever-present hunger and memories of the cold crowd in first.

No one who lived through it could forget the bitter winter of ’63. I was only five and our pipes burst. We ran a bath full of water to use for drinking and cooking. It froze over and we’d have to crack the ice to fill the kettle. And oh, those painful chilblains in my feet which plagued me from childhood to early adulthood.

I was always anxious about money, even as a child. So, is it any surprise I want a government that is fiscally sound?

Things didn’t get easier as I got older. The miners’ strike hit in the Seventies, the three-day week and the power cuts to conserve coal to fire the power stations. We were forced to gather around the fire for the benefit of light as much as warmth. I squinted to read by candlelight.

Again, I was aware of the politics debated around every hearth in these febrile times.

In 1973, Britain joined the Common Market and not everyone was happy about it.

Nadine Dorries as a baby with her father, a bus driver, in Liverpool. She grew up in Breck Road, Anfield, one of the most economically and socially deprived wards in the country

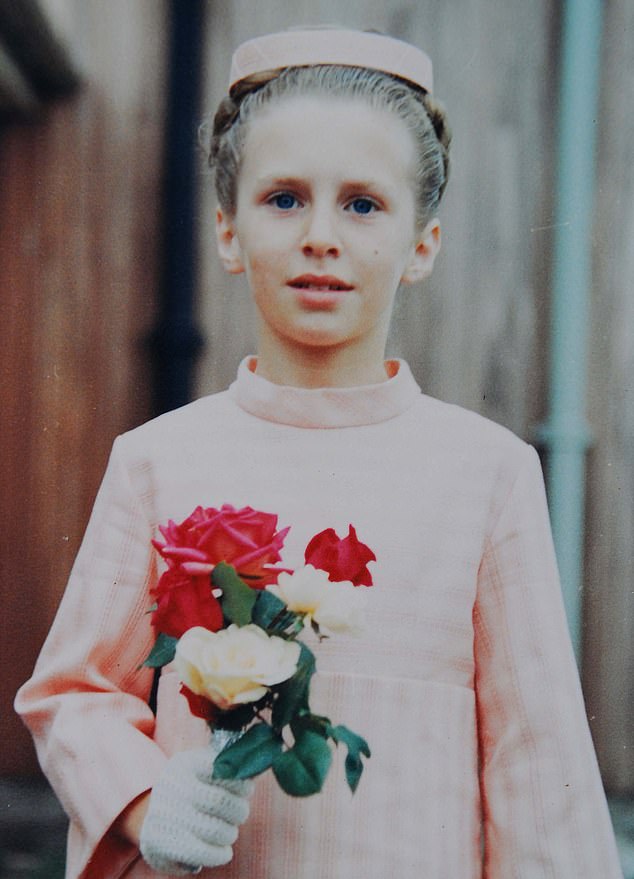

‘I try to remember happy times, of course. But the lack of money, the ever-present hunger and memories of the cold crowd in first,’ Nadine says. Pictured aged nine in 1967

Terrorism was a fact of everyday life – the IRA bombing of the Old Bailey, the Kings Cross and Euston explosions, Selfridges, Harrods… We Boomers may have missed the war, but not the bombs.

I remember, with absolute clarity, the moment I began to really take an interest in party politics. We were living in Runcorn, a suburb built to rehouse families like mine who were moved out from central Liverpool as part of the slum clearance programme.

It was 1974, I was 17 years old, and the country was in the grip of economic and political turmoil as voters headed to the ballot box for the second time in six months. Interest rates hit 17.5 per cent.

On election day, my neighbour was mopping her front step, and I asked her who she would vote for and why. She stopped and, leaning on her mop, explained to me that, as far as she was concerned, Labour was the party of the workers and the Conservatives the party of the family but added: ‘What have we got to conserve, eh? Nothin’.’

She was right. We truly had nothing. It was that moment I realised the only way to escape nothing was to educate myself and flee the concrete estate and the fate that awaited me if I remained. I wanted to be a nurse and my O-level results were good, despite the challenges I’d had to face along the way.

I probably read that acceptance letter from the hospital a hundred times. In the words of Tracy Chapman, it was my ‘fast car’. Maybe I could get somewhere… any place was better. My fast car arrived just as a minority Labour Government was elected with a majority of three.

I began my training the following year and moved into the nurses’ home. I could barely feed myself on the salary I earned. The situation in the hospital was dire. I spent half of my time going from ward to ward to beg for bed linen or for bags of IV fluid. I remember one patient writing the date on her sheets in biro each day we apologised for not changing them because we were short of clean ones. Now the hospitals had ‘nothin’’.

Government borrowing was at an all-time high. On September 28, 1976, the then chancellor, Dennis Healey, was sitting in the VIP lounge at Heathrow Airport with a G&T in his hand en route to a meeting of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

He was told that the pound was plummeting. He headed back to the Treasury and announced he needed to borrow a record $3.9billion from the IMF. Britain was effectively bust and truly the ‘sick man of Europe’.

Nadine trained as a nurse and was shocked by the dire situation in the hospital, sometimes unable to change patients’ sheets because there were no clean ones

Everything Margaret Thatcher stood for – aspiration, a small state, lower taxes, faith, family and defending our sovereignty and our nation – resonated with Nadine

I first heard the name Margaret Thatcher standing at a patient’s bedside taking his pulse. We were watching the Six O’Clock news on the TV at the end of the ward. Mrs Thatcher had ousted Edward Heath to be elected leader of the Tory Party in February 1976.

‘That’s what we need,’ my patient said to me. ‘A shop keepers’ daughter from Lincolnshire. She knows what’s what, she’ll see us right.’

Everything Margaret stood for – aspiration, small state, lower taxes, faith, family and, most importantly, defending our sovereignty and our nation, resonated not just with me but everyone back on my council estate.

When the ’79 election came, our neighbours’ kids ran after a van with a loudspeaker on top telling people to vote Labour chanting ‘Maggie, Maggie’.

Margaret Thatcher was elected with the hard-won votes of the working class, and in 1980 she repaid those who lived on council estates like mine with a policy that transformed our lives.

I saw the impact of giving council tenants the right to buy their properties almost immediately.

Packing cases from the docks which had served as dividers between front gardens were ripped up and replaced with painted picket fencing. Flowers were planted, and a row of green front doors became a rainbow as one proud, new homeowner after another chose to express their individuality by painting their door the colour they wanted and not that which the council dictated. Suddenly, we were kings and queens of our very own castles.

The introduction of the Enterprise Allowance Scheme – providing a weekly payment to unemployed people of working age who wanted to set up their own businesses – was another gamechanger. Our country was beginning to heal, to flourish even. And seeing that, seeing Thatcher’s policies in action, is how a girl from a Labour-dominated Liverpool council estate became a Conservative.

For Labour, property was theft. For Margaret Thatcher, it represented freedom. She had given us back our identity, a sense of purpose and she had indeed set us free.

We may have had ‘nothin’’ to conserve once – but thanks to Maggie, we did now.

She stood for a council seat and then for a parliamentary seat, Hazel Grove near Manchester, in 2001 before being elected to Mid-Bedfordshire in 2005

‘I soon learnt that if you were a Conservative MP on the right of the party, it was a very lonely place.’ Nadine is pictured in her office at Portcullis House in 2011

In 1987, Mrs Thatcher won an historic third general election and polled more votes than she had in 1979. And yet her reward was to be callously brought down by her MP colleagues. I struggled with this, but it fuelled my determination to do something. In 1996, when the Tories under John Major were about to crash and burn, I decided to join the Party and become part of the recovery.

I was no longer a nurse. I’d started a business when my three daughters were at nursery – a child day care service for working parents – and it was so successful that BUPA bought it. I could now pursue my own political passions.

I stood first for a council seat and then for a parliamentary seat, Hazel Grove near Manchester, in 2001. Eleven years had passed since Thatcher was toppled, but it was clear on the doorstep that the public were not going to forgive the Tories and their act of treachery any time soon. I was defeated but became an adviser to the then shadow chancellor, Oliver Letwin (himself a former adviser to Mrs Thatcher) before I was elected to Mid-Bedfordshire in 2005.

Sadly, I didn’t get off to a good start. I opposed Tory leader David Cameron’s announcement on all women short lists. I opposed his plans to close grammar schools. My experience as a nurse compelled me to introduce a bill to try to reduce the upper limit for abortion from 24 weeks to 20 which was fiercely opposed by most Labour MPs and many Tories too.

And of course I was a natural Eurosceptic.

Indeed, I soon learnt that if you were a Conservative MP on the right of the party, it was a very lonely place. Back then it was the modernisers – who disregarded Thatcher and her legacy – who had the upper hand. Anyone with an ounce of ambition who mentioned her name or quoted her, did so at their peril. At times, it was as if she had never existed. Later, MPs like me would be dismissed as ‘swivel-eyed loons’.

In 2010, we finally succeeded in ousting Gordon Brown and Labour and formed a coalition government with the pro EU LibDems. That was something else I opposed. I wanted to go back to the country for another vote.

It was the following year that politics as we knew it in the UK changed and the battle between the Europhiles and Eurosceptics that was tearing the Party apart came to a head.

From left, Nadine Dorries, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Suella Braverman and Chris Heaton-Harris attend the weekly Cabinet meeting in 2022

The official Cabinet picture for 2022, taken in the garden of No 10 in July

Outgoing prime minister Boris Johnson leaves 10 Downing Street in September 2022

More than 100,000 members of the public had signed a petition calling for referendum on EU membership. It led to a landmark vote in the Commons on October 25, 2011 when 81 Tory MPs became lions, defying Cameron’s leadership and voting for a referendum on our continued membership of the EU.

The motion was defeated overwhelmingly but it was the largest postwar rebellion on Europe and set us on the path to the EU Referendum in June 2016.

No one should be in any doubt about the role Nigel Farage played.

The Tory Party was running scared of him and the rising popularity of UKIP. In their arrogance, Cameron & Co assumed they could control the outcome of the referendum by throwing the weight of the government machine behind Remain and consign Nigel Farage to the footnotes of history. A big mistake.

When Boris Johnson became leader in 2019 – a man personally compelled to honour the democratic will of the people who’d voted in the Referendum – I knew we had turned a corner, despite the difficulties he faced with Remainer MPs in his own party. In December of that year, he took us to the country, won a stonking majority – and within weeks had delivered Brexit.

In May 2020, at the height of Covid, he made me a minister of state at the Department of Health and Social Care. In September 2021, I took my place at the Cabinet table as Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport.

Of course, the ‘reward’ for Boris Johnson’s electoral victory and his phenomenal ability to deliver echoed that of Margaret Thatcher. He was brought down and removed from Westminster by his own colleagues and key aides. I will always be a true and loyal friend to Boris and I will always defend how he conducted himself as PM.

After what they did to Boris, I no longer wanted to work with MPs I regarded as regicidal and self-serving and who stupidly refused to believe that what they were doing could possibly result in a left-wing government taking power. I resigned as an MP, left Westminster and spent two years writing two books, The Plot: The Political Assassination of Boris Johnson, and then Downfall: The Self-Destruction of the Conservative Party, detailing for the record how the Party I once loved had consumed itself.

‘I will always be a true and loyal friend to Boris and I will always defend how he conducted himself as PM,’ says Nadine Dorries, pictured in November 2012

After resigning as an MP, Nadine spent two years writing books detailing how the Conservative Party had consumed itself

Today, Britain is in turmoil. Broken. Nothing works. People don’t feel safe. You can’t walk the streets of our capital with your phone in your hand or wearing a fancy watch for fear of them being ripped from you. Knife crime is out of control. Shop lifting endemic.

In too many of our cities, hotels are being filled with illegal immigrants, 80 per cent of whom are young males who’ve travelled through safe European countries to get here. They want to be in Britain because they know they will be housed, fed, given money and run a minimal risk of ever being deported.

Following last month’s ruling by the Court of Appeal in the Government’s favour – overturning a ban on The Bell Hotel in Epping being allowed to house migrants – it is now clear that the rights of illegal migrants supersede those of local people.

I believe you can feel a sense of dread taking hold of communities up and down the country as a result. People are afraid to speak freely for fear of being cancelled or even to hoist our patriotic flags.

Two-tier policing has become mainstream; our farmers have been crushed, and the economy is sinking like a stone as inflation, ever higher taxes, a ballooning welfare bill and rising unemployment figures take their toll.

This is just the start. We have another four years of this Marxist government left to run.

I have known Nigel Farage for some considerable time, and no one can deny that he believes in what he says because he’s been saying the same thing for more than 30 years. That illegal immigration is out of control, and it impacts everyone: from the NHS struggling to cope with an ever-increasing demand on its resources, an education system in which working-class white children are being failed, and a housing system that ignores the needs of the indigenous population.

As the interest on the national debt increases, global financial institutions are looking on in disbelief and fast losing faith in our fiscal competence or our ability to rein in public spending. That lack of confidence threatens the very foundations and stability of our economy. What we endured back in the Seventies threatens to become our future.

The budget on November 26 will impose even further penalties on those who have done the right thing – who have worked hard and saved; those who risked everything to start a business or have toiled every day of their lives to provide for their families and to leave something for their children and grandchildren in this economically unstable world. They will be punished again.

The time for action is now and I believe that the only politician who has the answers, the knowledge and the will to deliver is Nigel Farage.

‘The time for action is now and I believe that the only politician who has the answers, the knowledge and the will to deliver is Nigel Farage,’ says Nadine Dorries

‘On the issues of law and order, immigration, the need to drastically cut public spending and boost growth and to support Ukraine, I am 100 per cent behind Nigel’

Nigel and I will never agree about everything. Neither of us are political robots. But on the issues of law and order, immigration, the need to drastically cut public spending and boost growth and to support Ukraine, I am 100 per cent behind Nigel. When we disagree, it will be in private.

I have sat at the Cabinet table. I have run a government department. I know how an effective government can work when ministers are united behind core beliefs and objectives. But I’ve seen the other side too. How personal ambition, avarice, ego, hubris can corrupt. It’s time for change. Yes, it’s time to make Britain great again, to remember who we once were, what those who gave their lives in the Second World War fought for – and to remember why a government is elected. To keep us safe and for the nation to prosper. Only Nigel gets this.

I know this may not be universally popular with all members of Reform, but I do believe there will need to be an accommodation on the right of the political spectrum at a future election.

Jeremy Corbyn’s yet-to-be named new party will unite with the Greens, the pro-Gaza independents and the extreme Left to split the Labour vote.

If the vote on the right is also split, it may pave the way for a Left-wing government even more extreme than the one we have now. And when that happens, to paraphrase a memorable headline: will the last person to leave the country please turn the lights off – if indeed we still have electricity.

I may be transferring my allegiance to another political party. But I am still being true to who I am and to the reason I became involved in politics in the first instance: to keep a left-wing Labour government out of No 10 – for all our sakes.