A new study reveals how the Temple of Venus has stood the test of time – and it suggests the Romans were even more clever than we gave them credit.

The stunning octagonal structure at Baiae near Naples, southern Italy has stood for nearly 2,000 years in a geologically active area.

Built to the orders of Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century, it features a great hall that served as a thermal building within a large complex of public baths.

Scientists at the University of Naples Federico II have analysed samples around the structure’s base to uncover what’s made it so long-lasting.

They found the Romans deliberately added volcanic materials as they knew it would make the 80ft-wide-building more durable.

Roman builders selected different volcanic materials depending on the structural requirement, according to study author Dr Concetta Rispoli.

‘The temple has remained standing because its geomaterials behave almost like a natural rock,’ she told the Daily Mail.

‘Instead of weakening, the materials continue to “lock together” and consolidate as they age.’

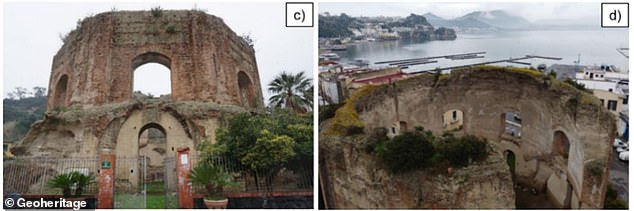

The stunning octagonal structure at Baiae near Naples, southern Italy has stood for nearly 2,000 years in a geologically active area

Commissioned by Emperor Hadrian, it was the grand bathing pool of Baiae’s imperial thermal complex. It features an octagonal exterior plan that becomes circular on the inside

The temple is in a remarkable state of preservation despite being nearly 2,000 years old and in the Phlegraean Fields, a volcanic region affected by ‘bradyseism’ – the slow rising and sinking of Earth’s surface caused by volcanic activity.

Mysteriously, the material used to build the Temple of Venus in Naples has endured even as Earth’s surface around it sank.

Steady ground movement has lowered the temple to roughly 20 feet (six metres) below today’s surface.

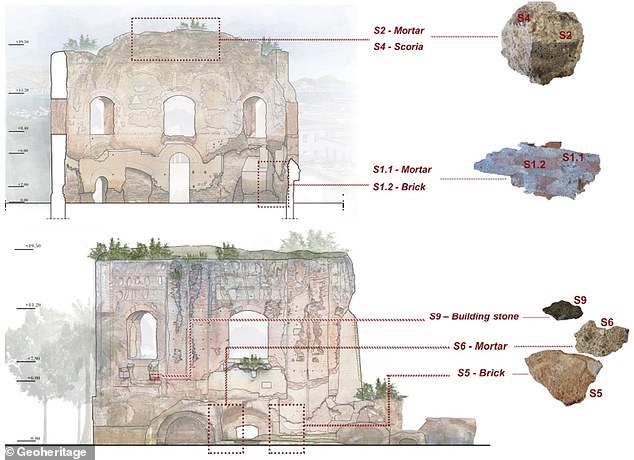

For the study, the team collected nine samples from the Temple of Venus, including mortar, bricks and several types of volcanic stone.

They also collected efflorescence – the white, powdery deposits of soluble salts form on the surface of bricks and other materials.

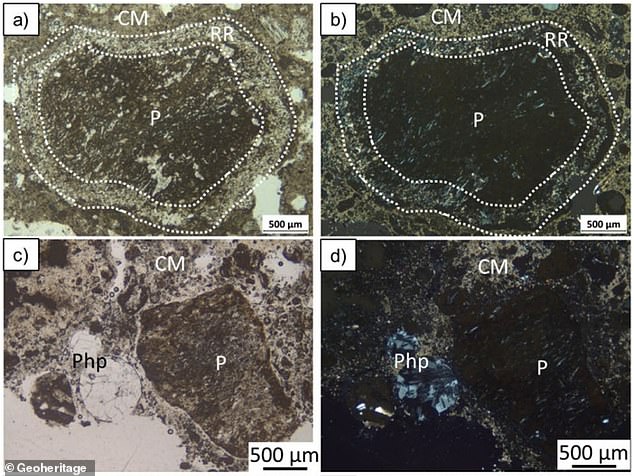

They examined samples under powerful microscopes and X-rays to identify each material’s structure and texture specific chemical ingredients.

According to the findings, the bricks and mortars were lime-based materials mixed with volcanic particles – likely an intentional addition by the Romans.

‘In simple terms, the Romans built this monument using materials that react together and become stronger over time,’ Dr Rispoli told the Daily Mail.

This sketch of the Temple of Venus shows the location of some of the nine investigated samples

Pictured, polarized light microphotographs bedding mortars used in the creation of the Temple of Venus by the Romans

She continued: ‘The key element is the use of local volcanic materials from the Phlegraean Fields.

‘When these volcanic components were mixed with lime, they triggered a chemical reaction that gradually formed new minerals inside the mortar.

‘This process made the structure remarkably solid and resistant to water, humidity and ground movements.’

The academic pointed to one kind of volcanic ash known as pozzolana, which was ‘was far more than a simple filler’.

‘When mixed with lime, pozzolana produced chemical reactions that created a dense, long-lasting mortar,’ she told the Daily Mail.

‘This technology allowed the Romans to build large, stable structures even in an active volcanic landscape.’

The team also found evidence that the scoria, a lightweight volcanic rock often used in landscaping and construction, was imported from the Vesuvian region slightly further east where one of the most famous and deadly volcanic eruptions took place in the 1st century.

‘Very light scoria was used in the upper parts of the building to reduce weight, while stronger volcanic tuffs and lavas were placed in supporting areas,’ Dr Rispoli added.

The structure was named the Temple of Venus – after the discovery of a statue of the Roman goddess of love and desire in 1595

‘This careful material selection is one of the reasons the monument is still standing after nearly two thousand years.’

The study provides further insights into the ‘technical skills achieved by the ancient Romans, and how their production technology was aimed at innovation, quality, sustainability, durability and, not least, beauty’.

‘From an architectural perspective, the Romans inspired many populations, both past and present,’ Rispoli and colleagues say in their study published in Geoheritage.

‘Their ability to build monuments starting from simple geological materials and obtaining more complex ones that would last over time has been, and still is, object of interest for researchers.’

Famously, the Romans founded one of the greatest empires in history, conquering the Mediterranean area and half of Europe.

The sign of their expansive influence and dominance can be seen through buildings, roads, aqueducts, temples and monuments.