After 38 years as a journalist in Washington, 23 of them on the White House beat, I thought I had seen it all. That includes covering the first term of President Donald Trump, whose specialty is thinking – and going – outside the lines.

But this past year has felt truly unprecedented. For me, it started on Christmas Eve 2024, when I made the first of two visits to the D.C. jail. Outside, I spoke with participants holding a nightly vigil for those convicted in the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol. Their fervent hope: that the soon-to-be reinstalled President Trump would pardon the convicts, some of them friends and loved ones of those standing watch.

Those jailhouse visits would foretell a year of tumult – of a president who would sweep back into office feeling vindicated and determined to flex his power, shaking up Washington while rewarding friends and punishing enemies.

Why We Wrote This

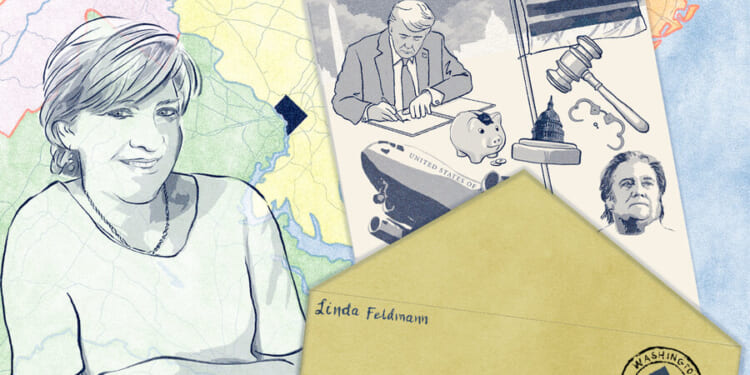

The Monitor’s Linda Feldmann has covered numerous administrations and historic events over her decades in Washington. But, she writes, President Donald Trump’s second term has been unlike any other. She reflects on having a ringside seat during this momentous and tumultuous year – under a president who returned to office determined to flex his power, shake up the federal bureaucracy, and leave his mark on the nation’s capital.

Fast forward nearly a month, to Inauguration Day, when the Monitor’s turn came up to serve in the “press pool.” From the crack of dawn to late that night, I had a ringside seat on a signal day for two American presidents, and the duty to write regular reports for the wider press corps. In the morning, we in the pool tracked outgoing President Joe Biden, and at the stroke of noon, we were like Alice in Wonderland, going through the looking-glass into the new reality of a second Trump term.

In the motorcade, we careened through the streets of Washington, going from event to event, including multiple inaugural balls. That night, in his triumphal return to the Oval Office, Mr. Trump answered the prayers of the vigil-keepers, granting clemency to almost all of those convicted of breaking the law in connection with the Jan. 6 riot, nearly 1,600 people.

Issuing pardons, an enumerated presidential power in the U.S. Constitution, would prove to be a regular and controversial aspect of Mr. Trump’s first year back. So, too, would many other defining features of this extraordinary period – from the widespread layoffs initiated by his Department of Government Efficiency to the sweeping immigration crackdown to the disruptive tariffs imposed on nearly every U.S. trading partner. Mr. Trump also took aim at major universities over alleged antisemitism.

In May, the press pool rotation put me again in the Oval Office, when the discussion turned to Mr. Trump’s efforts to ban foreign students from attending Harvard University. I seized the opportunity.

“Why would you not want the best and brightest from around the world to come to Harvard?” I asked Mr. Trump.

The president pivoted to talking about how some Harvard students in recent years have needed what he called “remedial math.” When I tried to nudge him back to my question, he wouldn’t have it. “Wait a minute,” he said, persisting in his argument.

The clip of that Q&A spread quickly. In the end, Mr. Trump allowed Harvard to keep accepting foreign students, then went further: He decided to issue 600,000 visas for students from China, to the chagrin of his MAGA base. American schools, he said, needed the tuition money.

Breakfasts with Bannon and Vought

Understanding a presidency – and the wider universe of White House-adjacent characters – requires persistent questioning and close listening. As the moderator of Monitor Breakfasts, I had the opportunity this year to host two key figures from Trump world: former senior adviser Steve Bannon and current budget director Russ Vought.

Hosting Mr. Bannon for breakfast was controversial, given the MAGA activist’s provocative views, including his insistence that Mr. Trump won the 2020 election and would serve a third term, despite the Constitution’s two-term limit. But Mr. Bannon also had the president’s ear. The day after our breakfast, he spent three hours at the White House, including lunch with Mr. Trump. Mr. Bannon was adamant that the United States should not attack Iran’s nuclear facilities, but four days later, Mr. Trump did just that. The Monitor’s YouTube video of the breakfast became our most-watched ever, with more than 443,000 views.

Our breakfast with Mr. Vought – director of the Office of Management and Budget and, before that, an architect of Mr. Trump’s second-term agenda – was less controversial. But as a key member of the administration, he’s more consequential. Dubbed by some the “shadow president,” he has the power to make things happen, including a number of dramatic cuts to government programs and spending that have occurred without congressional approval.

Most memorably, he said this at our breakfast: “The appropriations process has to be less bipartisan.”

Our YouTube audio of the Vought breakfast didn’t come close to the viewership of the Bannon video, but I still recommend it as a path to understanding how this administration operates.

Changes to the White House – and Washington

As a Washington resident and longtime observer of the White House, I’ve been struck by Mr. Trump’s changes to the building itself. First, there was the addition of much gold filigree to the Oval Office, and the paving over of the Rose Garden. More recently, Mr. Trump drew international headlines for tearing down the East Wing to make way for a giant ballroom. I will never forget the sound of jackhammers that grew ever-louder as I walked down 15th Street NW toward the scene on the morning the demolition began. For weeks, the scope of the project was a point of contention for the president and his chief architect, whom he ultimately replaced.

Mr. Trump’s deployment of National Guard troops to the streets of Washington was another controversial decision. The president had made the move in August in the name of addressing crime, but like the June deployment to Los Angeles, it seemed largely performative.

In mid-September, while walking home one day, I struck up a conversation with a Guard member, who said he was a police officer from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He had been in Washington three weeks, he said, and seemed ready to go home.

“Have you been involved in any police actions here?” I asked. “Nope,” he responded. Been sent to any bad neighborhoods? “No,” he said. “Are there any?”

Two months later, on Thanksgiving Eve, the unthinkable happened. Just blocks from the White House, a gunman shot two Guard soldiers, killing Spc. Sarah Beckstrom from West Virginia. The alleged gunman was a young man from Afghanistan who had worked for a CIA unit there during the war, and was later granted asylum in the United States.

Before the tragic events of Nov. 26, the news media had often portrayed Guard members on patrol here as maybe a bit bored, though at times helpful. Guard troops have been seen picking up trash and helping people carry groceries or change a tire. Since their arrival, crime is down in D.C. But so is tourism.

Now, after the ambush at Farragut Square, the National Guard’s mission is laden with fresh import. In a deployment that had already been extended to Feb. 28, Guard members are now all armed. Mr. Trump has ordered 500 more troops to D.C., adding to the 2,000 already here. And he’s halted immigration applications for migrants from 19 countries.

As the first year of Mr. Trump’s return to office comes to a close, I’m reminded that the daily drama that is life in Washington extends far beyond its borders, affecting lives near and far.