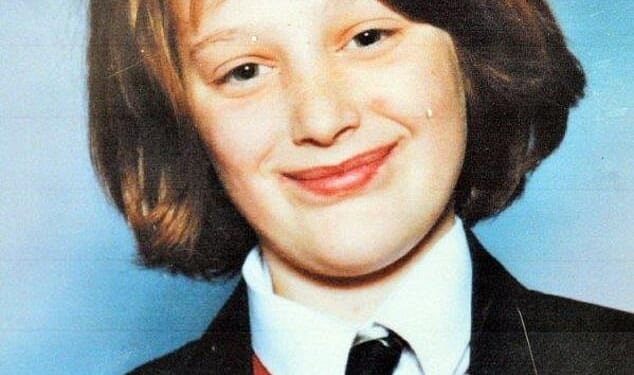

When I was a teenager, a girl went missing from my hometown, Blackpool. Her name was Charlene Downes and today marks the 22nd anniversary of the day she disappeared.

On November 1, 2003, Charlene, 14, spent the day wandering around town with her sister, Becky. At around 7pm they bumped into their mum, Karen, who was handing out leaflets for a local restaurant in the town centre.

They had a quick chat. Charlene said she was going out to meet some friends and Karen told her not to stay out too late.

That was the last time she ever saw her daughter.

At first, the police classed Charlene as a runaway. But the more time passed, the clearer it became that something serious had happened to her.

I have a vague memory of the ‘missing person’ posters going up around the town centre and her school photo being displayed on lampposts and bus stops.

A few years later, two Middle Eastern men who worked at a local fast food takeaway were accused of her murder. It was claimed that they disposed of her body by cutting it up and turning it into kebab meat. Charlene became known, cruelly, as ‘kebab girl’.

It’s a horror story that has haunted Blackpool for decades. And one that is surely too gruesome to be true.

On November 1, 2003, Charlene, (pictured) 14, spent the day wandering around town with her sister, Becky

Nicola Thorp (pictured) writes: I was a teenager, a girl went missing from my hometown, Blackpool

Yet, to this day, some people in Blackpool believe that this was Charlene’s fate.

After all, that is what both the Lancashire Constabulary and the Crown Prosecution Service insisted had happened to her at the time. Google her name, and you’ll find headlines such as, ‘Girl’s body “put into kebabs”.’

But there is no forensic evidence to prove, conclusively, that she was murdered in the first place, let alone turned into kebab meat.

The truth is the kebab story was just a theory – a false one – put forward by a police investigation team desperate for a conviction in what has become Lancashire’s longest running and most expensive homicide case.

It appalled me that Charlene’s disappearance had been trivialised in this way.

So intrigued was I by the narrative that had developed around Charlene that, three years ago, I began to to look into her case. I soon discovered new information about her movements on the day she went missing, including a mysterious interaction with a man named ‘Ronnie’ who is said to have handed her £70 cash.

The meeting between the two of them that day could prove critical to solving the question of her disappearance yet, more than 20 years later, the police still have no idea who he is.

I pressed on with my inquiries, determined to uncover the truth – little knowing the project would soon become my full-time job.

Now, my investigation has been turned into an eight-part podcast series called Charlene: Somebody Knows Something, which is available to listen to on the Daily Mail’s podcast network The Crime Desk.

It is a terrible and shocking story shrouded in false rumour, police failure and sexual exploitation.

And one that, for the sake of Charlene, as well as those who were falsely accused, everbody should hear.

The police were slow to act after Charlene was reported missing. Because they treated her as just another teenage runaway, it was weeks before they began to take the idea seriously that she could have been murdered.

By 2004, the fear was that she could have fallen victim to grooming gangs operating in Blackpool.

At the time, police considered kebab shops and other outlets in the fast food industry to be hubs for the sexual exploitation of under-age girls by older men and, in 2006, almost two-and-a-half years after Charlene went missing, two takeaway food workers were arrested.

Iyad Albattikhi, 29, was charged with Charlene’s murder and his associate, Mohammed Raveshi, 50, was charged with disposing of the body. Which is where the kebab story comes in.

In 2007, both men were put on trial. As part of their investigation, police had installed hidden microphones in Raveshi’s flat and car. They played sections of these tapes to the jury, along with a transcript produced by one of their officers. This officer was considered an ‘expert’ by the court, despite having had no formal training in forensic audiology.

The CPS claimed the tapes had caught the two men discussing Charlene’s murder and the disposal of her body, something both men denied.

But the jury couldn’t decide on a verdict, so they faced a retrial.

Then, in 2008, just weeks before the second trial, the prosecution suddenly withdrew its case, citing ‘issues with the evidence’.

Many thought the two men had been let off on a so-called ‘technicality’, but the ‘technicality’ was this: the evidence against them did not exist.

While the police investigation concluded that Charlene had been groomed by a number of takeaway workers in Blackpool, there was no evidence that she had ever met Raveshi.

As for his co-accused, Albattikhi, I have interviewed several women who claim to have witnessed Charlene and him together, although he denies ever meeting her.

Meanwhile, the audio recording ‘evidence’ captured by hidden microphones installed in the home and car of one of the men was found to have been obtained in a such a way that it was, at best, inadmissible in court and, at worst, downright fraudulent.

It took me years to get my hands on the last remaining copies of those tapes and, when I did, I discovered that the quality of the recording made at the suspect’s home was extremely poor, partly because it had been installed next to a television.

The police officer who transcribed the tapes claimed she had heard clear confessions from the pair but, in reality, there was little more than muffled, unintelligible conversation. You can listen for yourself in episode two of the podcast.

When I interviewed Detective Superintendent Gareth Willis, who became senior investigating officer in Charlene’s case in 2022, he accepted the failings of the police’s initial investigation.

‘I want to acknowledge that we haven’t always got things right with this investigation,’ he said, ‘but I don’t really want to dwell on those failings.’

As for the ‘issues with the evidence’ he was unequivocal: ‘The covert material that was relied upon in court has been fatally undermined and it’s not accurate, it’s not truthful.

‘We all acknowledge that that evidence does not exist. In the eyes of the law, those men are innocent and we do not have any evidence to suggest anything to the contrary.’

The men were eventually released and each paid around £250,000 in compensation for false imprisonment.

In total, Raveshi spent two-and-a-half years in custody – the longest time served by anyone without a conviction in Lancashire’s history – on charges of disposing of the body of a girl police had no evidence he had met. No one else has been charged over the disappearance.

I knocked on Raveshi’s door when I started my own investigation into the case and, after telling him I wanted to make a podcast series about Charlene’s disappearance, he invited me in. Eager to talk, he sat and spoke with me for many hours on a number of occasions, handing over court documents and legal paperwork.

While I was grateful, I couldn’t help wonder why a man whose life had been destroyed by the case would want to reopen old wounds.

But as he put it himself: ‘Even if tomorrow she is found safe and sound, people will still think I’m a murderer.’

Aside from a determination to clear his name, Raveshi wanted me to take a deeper look at the reasons why he ended up on trial for murdering a girl he says he has never met. He is now convinced he was framed for Charlene’s disappearance by the police, an avenue I explore in-depth in the podcast.

Raveshi also steered my investigation in a new direction: he alerted me to a series of documents concerning the Charlene Downes investigation that had leaked online. As detectives interviewed her friends and acquaintances, they had discovered that Charlene was indeed a victim of child sexual abuse by men working in Blackpool’s night-time economy, although not the pair.

Indeed, police believe dozens of girls had fallen victim to sexual exploitation in the area. At the time, girls like Charlene were referred to as ‘child prostitutes’ in both police and Press reports. I have spoken to a number of these girls, who are now in their 30s, and one of them told me she was ‘not treated with any compassion or dignity whatsoever’ by the police.

It became clear that many had been dismissed or even belittled by police and told that the abuse was partly their own fault for mixing with the ‘wrong crowd’.

Although detectives discovered that grooming was taking place in Blackpool town centre, they had little information about where Charlene might have gone. One line of inquiry led me to social service records and police reports which appeared to paint a disturbing picture of the Downes family home and the men who were friends with her father.

In 2003, Charlene was living at home in Blackpool with her mother and father, Karen and Bob Downes, her grandmother, and her younger brother, Robert Jnr.

Speaking with those who knew her best, I learned that Charlene was a cheeky, confident teenager. She loved Westlife and Darren Day, animals and children. On the surface, she was a typical millennial teenager. But behind closed doors, she was a victim of child sexual abuse at the hands of several men, some of whom she had first met in her own home.

Her two older sisters had moved out of the family home, with 16-year-old Becky choosing to live with an older man, a friend of the family, following a series of arguments with her father. Bob liked to drink. He was a fixture at his local pub and often invited his ‘drinking associates’ – as he called them – to continue their sessions at home.

One of these friends was a convicted paedophile called Ray Munro and he was sleeping at the Downes’ family home the weekend Charlene disappeared.

Shortly before she went missing, Munro pleaded guilty to three counts of indecent assault and one of indecent exposure against three girls, as well as to indecently assaulting a six-year-old boy.

Munro had been a babysitter for all his victims, befriending their families before preying on the children. It was while he was on bail awaiting his sentencing hearing on Monday, November 5, that he spent another night at the Downes’ family home. On the Monday morning, with his daughter still missing, Bob Downes accompanied his friend Ray to court, where Munro was sentenced to four and a half years in prison.

As part of my investigation, the police confirmed to me that Munro was questioned over accusations that he had abused both Charlene and a friend of hers but he was never charged.

There was another man – again, a friend of Bob’s – who admitted to Karen that he was ‘in love’ with her 14-year-old daughter.

When this man was spoken to by police after Charlene disappeared, he admitted to them that he had paid Charlene to perform a sex act on him. When I spoke with Lancashire Constabulary, they told me that this man had not been placed under caution before making his admission, meaning they could not use it as evidence.

With Charlene no longer around to testify, he faced no legal consequences.

As for Karen and Bob, there is no evidence to suggest that they were in any way responsible for Charlene’s disappearance.

But leaked social service records show that there were concerns Charlene had been physically assaulted by her father.

I spoke with one of Charlene’s friends from that time, who alleged she witnessed two occasions on which Bob had been violent to Charlene, including one time where she alleges Bob choked his daughter.

Bob admitted to me that he had physically disciplined his children but denied ever choking Charlene or otherwise putting his hands on her neck. During the initial trial, her family told the court there was no reason to believe Charlene would run away from home. But the above accounts suggest that there were plenty of reasons why she might.

It has been reported that police believe 16 men with convictions for rape, assault or violence had visited the Downes family home during her lifetime.

It’s all too easy to say Charlene didn’t stand a chance. But having read social service reports written before she disappeared, it’s clear to me there were plenty of chances for social services, doctors and police to have stepped in and saved her from what she was subjected to – and saved her life.

There is, too, one aspect of the day Charlene went missing that hasn’t been given the attention it deserves: the mysterious man who gave her that £70 in cash on the day she disappeared.

On that Saturday, November 1, at around 3pm, Charlene’s sister Becky watched as Charlene met a man on a pushbike near their home. He said his name was Ronnie. They spoke for a short while before he handed over the money.

Was he paying her in exchange for sexually abusing her? We do not know and he remains a mystery, although one witness spoke to me on the podcast with compelling information as to who this ‘Ronnie’ might be.

While the police have conducted numerous inquiries in a bid to establish his identity, they admitted to me that they have never been able to do so.

How can it be that – 22 years on – police have failed to put a name to the man who gave a 14-year-old girl such a large sum of money on the day she disappeared?

There are as many missing pieces in the timeline of Charlene’s disappearance as there are untold stories of abuse in Blackpool during that time.

Today, Lancashire Police have changed the way they deal with reports of sexual assault and child sexual exploitation.

There are now charities that can support witnesses through the process of reporting and services that can provide emotional support to victims who seek help, but do not wish to speak to the police.

And the only chance of bringing closure to Charlene’s case is for someone to come forward with new information. There still exists a £100,000 reward for anyone providing information that leads to the prosecution of Charlene’s killer.

I hope that my renewed focus on the case means that someone unable to tell the truth in 2003 will come forward now.

I am determined to rehumanise Charlene, the girl who had been reduced to a piece of meat in a headline.

Perhaps it will be someone who’s had an incorrect or incomplete grasp of the story – who thought that Charlene’s killer had already been found.

Someone who will listen to our podcasts and realise they have a lead that could change the direction of the whole investigation.

It’s never too late for justice.

Somebody out there knows something.