When Mum drove me to work that Sunday morning, I thought she seemed subdued – but then she hadn’t been her usual chatty self for more than a year, ever since she and Dad split up and she had moved out of the family home.

As I got out of the car she leaned across, her blue eyes crinkling with intensity. ‘You know I love you, don’t you David?’ she said.

This display was all off. I was 23 and living with her in rented accommodation (my older brother James, then 27, had already left home), and though used to hearing ‘I love you’, this was odd. It was also 9.30am and my shift at the restaurant was starting. I did not want to be late.

I had no idea Mum had a little plastic stool behind the passenger seat and intended to drive to Beachy Head in the South Downs, use it to climb over the fences to the cliff edge and throw herself off.

I was taking a late lunch order when I saw Mum’s cousin, Noel, and a police officer. ‘David, your dad’s been found dead,’ Noel said.

Suddenly, the air around me was screaming. My hands shook as I handed back my apron, in tears.

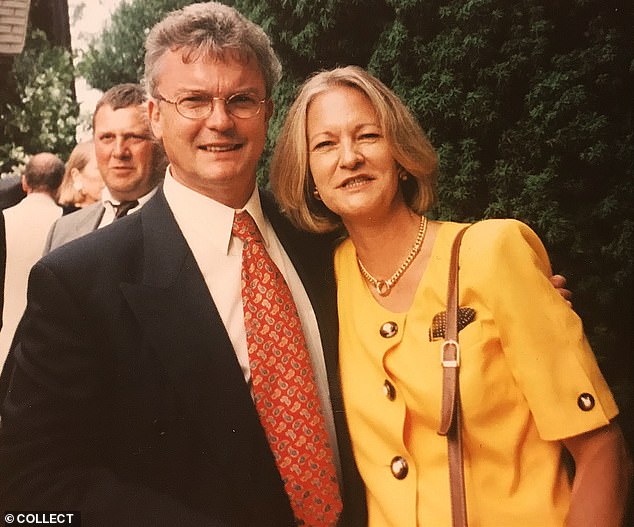

Richard and Sally Challen in the Nineties while she was under ‘coercive control’

Nothing made sense to me. My father’s body found at home. My mother found alive at Beachy Head.

It transpired that the day before – Saturday, August 14, 2010 – Mum had gone to see him at our old house in the leafy Surrey village of Claygate. They had been attempting a reconciliation, in spite of his behaviour.

Dad, 61, insisted she make him lunch and used to taking orders, Mum, then 56, trekked out to the shops in the rain.

As she was cooking, she checked the home phone, dialling 1471.

The last caller had been a woman she knew he was seeing.

As Dad ate lunch, she asked: ‘Am I going to see you tomorrow?’

‘No.’

‘Why?’

‘Don’t question me Sally,’ he had replied.

And with those words, my quiet and fearful mother picked up a hammer and hit him. More than 20 times to the head.

She covered his body with some old curtains, wrote a note and placed it on top of him.

I love you, Sally.

Before leaving, she cleared up, washing his dirty pans and dishes.

Mum was convicted of murder and sentenced to 22 years in prison. But nine years later, in 2019, I walked past crowds holding ‘Free Sally’ placards outside London’s Court of Appeal as her conviction was quashed.

The court recognised she had been suffering from a mental disorder at the time of the killing, which substantially impaired her ability to exercise self-control.

She was re-sentenced for manslaughter at the Old Bailey, marking the first time the court acknowledged the devastating psychological impact that coercive and controlling behaviour can have on a person’s mental state. The judge accepted that her so-called ‘moment of madness’ was in reality, the result of decades of abuse.

Coercive control had just come on the statute and as I read through the definition of the new offence, my childhood was all there…

Typical behaviours included humiliation, making someone think they are worthless, controlling their money, sexual assault and isolating them from friends and family.

An incident in isolation might seem innocent enough, but if you looked at the whole picture, these fragments became a horrifying mosaic telling the story of a life twisted by somebody else’s will.

I remembered my mother’s gaze, fixed imploringly on my father. His head, snapping round to her over the dinner table in anger.

The embarrassed silence at parties when he would run her down: ‘Thunder thighs… you wouldn’t want to see her without her clothes on.’

The endless denials when she accused him of cheating: ‘You’re going mad, Sally. You’re making it all up.’

As a result of my and my elder brother James’s campaign to free her, Sally’s Law was introduced in July 2023, a reform requiring courts to recognise coercive control as a mitigating factor in cases of domestic homicide.

Some 3,000 historical murder convictions are now being reassessed by the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

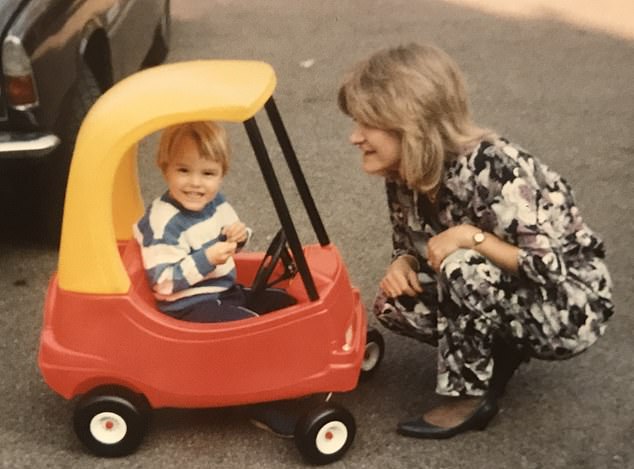

David Challen with his mum as a boy

At least five cases have already been reopened. I hope Mum’s story will offer a glimmer of hope to those still trapped by the justice system.

My dad, Richard, was a successful businessman, an entrepreneur who had built his second-hand car business from the ground up, starting by selling cars from a rented flat. He was good at his job and clients liked him.

When I went to identify his body, I stood over him and thought that, however he had treated Mum, he didn’t deserve this.

Yet, at the same time, I knew he was the architect of everything that had led to this moment.

Later, when I read Mum’s psychiatric reports, I learned that she had been violently raped – sodomised – by him for flirting with another man when we were on holiday.

I knew nothing of that, but I remembered their faces the next day, Dad’s tightly suppressed fury and Mum, muted and cowed beside him. He had created whatever had driven Mum to do what she did.

I remember Dad as loving when I was little. I used to love looking through our photo albums, seeing the story of our family.

There were my parents at their wedding, an English garden on a sunlit day. My mother, only 24, with loose hair, smiling in a high-necked dress. My father, dark-haired and grinning, twining his hands into hers.

Then there are photos of a typical family, the four of us grinning up from the photos outside an idyllic family home. It was a secluded four-bedroom house.

The long driveway burrowed down into the land the house sat on and from the road you could almost see right into all four corners of our house.

My favourite place was the back garden, where I had a little white Wendy house with a red trim on the roof.

Yet as I grew older, there was an almost imperceptible change, like a tide pulling away without anyone noticing.

The living room was Dad’s territory, where you’d find him watching Formula 1 or MotoGP. If you came in part way through a programme, he would pick up the remote to mute before slamming it down and ask, ‘Are you in, or are you out? Decide!’ He didn’t like people watching the TV without him. Using the DVD player was an even greater offence.

This was all his property and not for our use.

My mother’s domain was the kitchen, on the other side of the house. She was a great cook and there was always something delicious to eat.

She was kind and compassionate. So when I heard what she’d done to Dad, I also thought: ‘This wasn’t her.’ Mum was from an upper middle-class Oxbridge-educated family. She met Dad when she was just 15 and he was 21.

He proposed a year later, while she was still at school, but she said they’d have to wait.

Her family disapproved of the relationship – they even tried to separate my parents by sending Mum to a finishing school in Brussels – but she returned as desperately in love with Dad as ever.

He did not propose again for nearly ten years, though he knew Mum was longing for him to ask.

I can now see it was a way of controlling her even then, making her wait.

She kept in contact with her relatives, especially her cousin Noel, but when we went to family parties, Dad never came with us.

When I look back at the ‘golden moments’ of my childhood, I remember being around six or seven years old and seeing happiness swim across Mum’s face as Dad handed her a small black box containing a gold necklace.

She beamed with joy. Somewhere along the line, though, the necklace disappeared. I later learned Dad had ‘confiscated’ it for some misdemeanour.

When I was ten and my brother was 14, we went on holiday to Los Angeles to stay with an old friend of my parents.

The atmosphere turned sour during a trip to the Universal Studios theme park, courtesy of an ex-girlfriend of Dad’s.

It seemed Mum hadn’t been made aware of this connection in advance, and as the ex-girlfriend led Dad through a special entrance to the park with us in tow, the silence between us all was tangible. A few days later I woke to hear adults arguing by the pool.

The holiday was over. Dad thought Mum was being over-friendly with our host.

Some months later, we had a family trip to see Star Wars: The Phantom Menace.

When we got to the cinemas in London’s Leicester Square, it was teeming with excitement – with hundreds of people dressed as Darth Vader and Jedi warriors. Mum wasn’t with us.

When I asked why, Dad snapped: ‘She’s busy.’

I didn’t know it, but she was still being punished for Los Angeles. That was the holiday on which she was raped. At friends’ houses, I looked on in surprise as their parents gave each other a kiss or hug for no reason. It felt odd to me – and far too much. More usual were Dad’s flashes of anger.

If my mother cooked food he didn’t like, he’d look at his plate disgustedly and say: ‘Why have you given me this?’ Mum’s face would fall.

Mum loved to tell stories around the dinner table, but if she talked ‘too much’, she would be trampled over by my father.

‘That’s enough, Sally,’ he would say with finality.

Mum would simply stare in front of her, pretending he hadn’t spoken. I couldn’t bear him talking to her like that.

Everybody felt the sharpness of his tongue.

He was scathing about my attempts to learn guitar – an instrument I had taken up to please him – and humiliated me when I felt proud of something I had cooked. When his parents died, Dad used the inheritance to treat himself to a Ferrari.

It sat on the driveway, brash and red, garlanded with all sorts of expensive extras like F1 gear changing and a black grille on the rear bonnet. He joined the Ferrari Owners’ Club and started travelling round Europe with his new friends, taking Mum along with him.

He had already alienated many of her friends and turning her into a Ferrari wife was a way of further isolating her.

In my late teens, Dad made a new friend, who came around one night in a black dinner suit. Allegedly, this man was going out on a date and had asked Dad to drop him off in the Ferrari. But that night, Dad didn’t return until hours later.

David Challen today. ‘I wish I had realised how lost my mother had felt,’ he says

And he became more cavalier, not returning Mum’s calls or texts. There was one line he’d use on repeat: ‘Don’t question me, Sally.’ She pulled me aside one day, asking: ‘Do you know anything about your dad going to the London Eye?’

Her voice was tight, brittle. ‘I found tickets in his coat pocket. I confronted him and he said I must have put them there.’

Had he expected her to believe that? Something was changing in her, breaking.

She became convinced a woman had been calling and started checking his phone. Mum recorded everything she found and demanded answers.

His response was always the same: ‘You’re going mad, Sally. You’re making it up.’

Eventually she caught him out. A number he had been calling weekly led to a brothel called Pandora’s behind Surbiton train station in south-west London.

Mum drove there and waited in a stairwell to confront him.

She was distraught at him visiting prostitutes and refused to allow him into her bedroom.

She felt violated in every single way. Yet, still she did not leave.

It was only a year later, when on a family trip to the Maldives, that it finally unravelled.

Mum leaped at the opportunity to be social on holiday, flashing smiles to fellow guests and giving them a compliment or regaling them with an anecdote.

Dad stayed silent.

On the final evening, a local DJ played in the bar. I watched with a horrible sense of premonition as couples started to dance. Dad was staring straight ahead. Mum leapt up and tried to persuade him on to the dance floor.

No dice: Dad was planted solid. I had witnessed this kind of scene play out countless times at parties – Mum dancing, smiling and cajoling him as he sat motionless, blank eyes boring into hers, demanding she sit back down.

Later that night, my brother and I were woken by Mum suddenly bursting into our room, jolting us awake.

Something about her was frighteningly off-kilter.

‘We started to argue [about the dancing],’ she told us. ‘And then suddenly… he was pushing me back to the room.

‘And when we got there, he grabbed me… I was screaming, and he… he was trying to cover my mouth. To shut me up.’

Mum looked stunned, but measured.

‘I’m divorcing him. I can’t take it any more. I can’t do it. His lying, his cheating. That’s it, I’m sorry.’

Inside I cheered. We would be free. Of course, it didn’t work out that way.

Eighteen months later she was charged with murder. I watched with resignation as the jury came to its verdict: Guilty.

Some of us witnesses had tried to describe the atmosphere in our house, but it wasn’t deemed relevant. What mattered was that Mum has been carrying around the hammer she used to kill Dad in her handbag.

I wish I had realised how lost my mother had felt. In the weeks leading up to the killing, she had told me something extraordinary – that even though she was divorcing my father, she might go back to him. If that was to happen, he was insisting she sign a post-nuptial agreement.

‘I would have to follow some rules…’

‘What rules?’ I asked, trying to stay even-toned.

She started reading from an email. ‘You will continue and complete the divorce with a £200,000 settlement.

‘When we go out together it means that: Together. This constant talking to strangers is rude and inconsiderate.

‘We’ll agree to items in the home together.

‘To give up smoking.

‘To give up your constant interruptions when I am speaking.’

I stared at her in amazement. What in the hell was she thinking? I didn’t know a great deal about divorce law, but I had a pretty good idea that £200,000 was a lot less than she would be entitled to after 31 years of marriage to Dad. Her hard-won freedom would be gone.

‘You’d be mad to sign that, Mum,’ I said. ‘Do not sign it, please. I’m begging you.’

‘Okay,’ she answered without arguing. She didn’t bring it up again. I thought she had seen the light. I was wrong.

It was prison, ironically, that opened her eyes.

During her first year she was put on the Freedom Programme, a course supporting victims of domestic violence and abuse.

The programme presents abusers as three different archetypes: the King of the Castle, the Bully, and the Sexual Controller.

‘You won’t believe it,’ she told me, ‘but everything they were saying, it was about me and your father. They were just describing everything that happened to me! Everything!’

There was a disbelief, almost horror in her voice.

I had always thought she knew Dad’s behaviour wasn’t right, but had wanted to stay with him despite that.

I realised then she hadn’t even known it was abuse. She was so young when they met, she had thought it was normal.

My heart broke a little for her.

It made me all the more proud, when she was finally free, to see her stand outside court and talk about coercive control and all the women in prison serving time for murder when it should have been manslaughter.

‘I know those women are there, because I’ve met them,’ she said.

My eyes welled up. How far she had come from the grey, compliant woman beaten down by a life of abuse and lost in a criminal justice system.

Here she was at last, speaking her powerful truth.

Adapted from The Unthinkable: A Story of Control, Violence and My Mother by David Challen (Brazen, £20). © David Challen 2025. To order a copy for £18 (offer valid to 21/06/25; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937

For support, call Refuge’s 24-hour national domestic abuse helpline on 0808 2000 247 or visit refuge.org.uk