This article is taken from the June 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

You are, let us say, a “young writer” on the south side of 40, chastened by the findings of the latest industry survey — these show that the mean authorial salary is around £7,000 p.a. — but with your first book contract lying on the desk before you.

The Secret Author would like to congratulate you, whilst proffering a few tips on how you might be able to sustain the career on which you have so optimistically embarked.

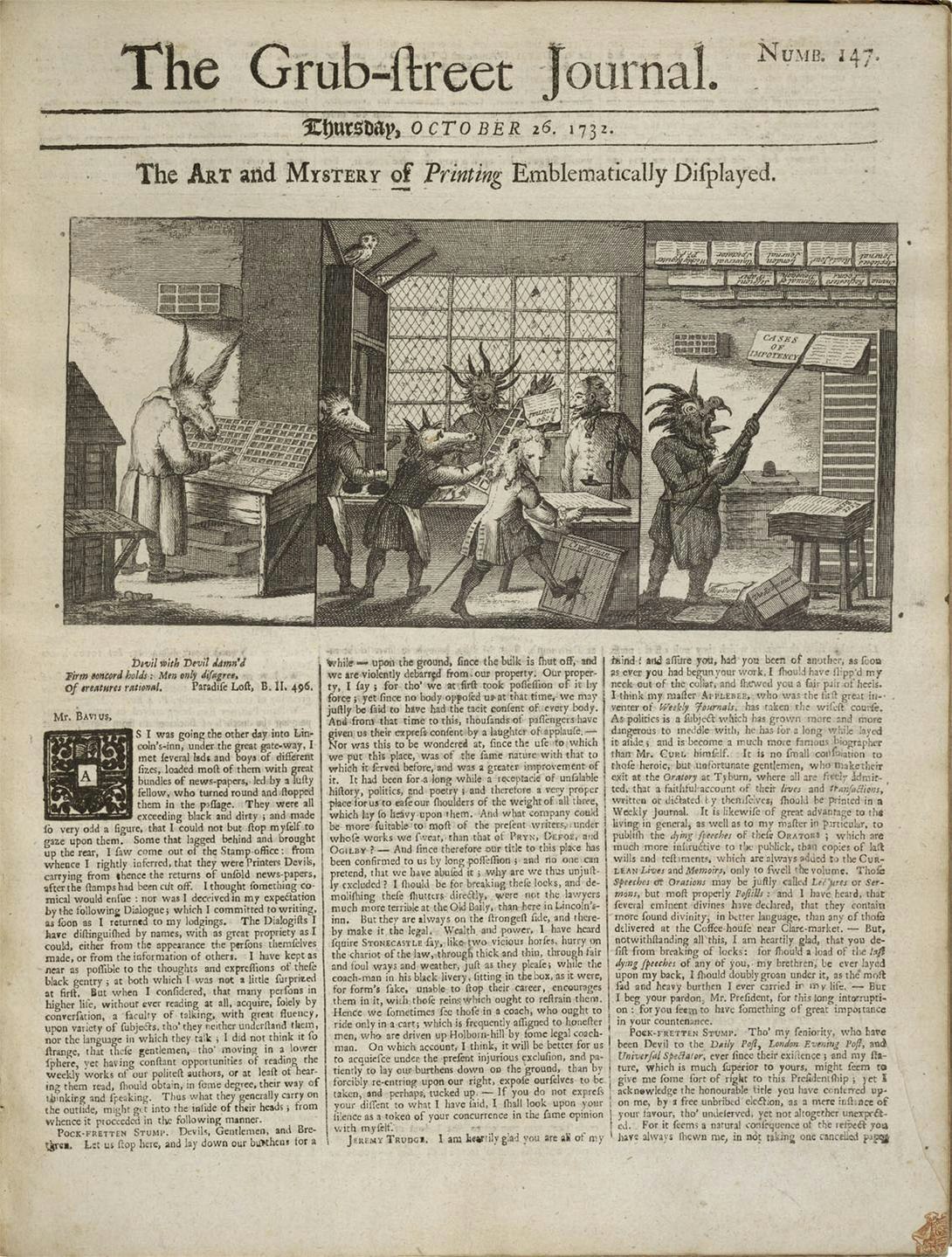

Civility is all. The old adage about being polite to the people you meet on the way up as you may very probably meet them again on the way down was never truer than on Grub Street.

Have a smile ready for the shy girl checking the proofs at the Literary Review: she will doubtless end up editing Vogue. The junior assistant who brings in the tea at Front Row is almost guaranteed to be controller of Radio Four 30 years hence.

The same rule applies to book reviewing. The author of the feeble novel you trashed in 2019 will, inevitably, be judging the literary prize for which your darling work is entered in 2029; no slight is so mild that it won’t be repaid with interest decades down the line. The Secret Author is still having trouble with a woman whose book he made the mistake of mildly disliking back in 1995.

Watch your politics. Whatever your private ideological leanings, always publicly proclaim an attachment to the left-liberal Guardian/New Statesman/London Review of Books line. Nobody ever got anywhere in the modern literary world by saying that they voted for Brexit or claiming that Nigel Farage is unfairly maligned.

Similarly, make sure you return publishers’ diversity surveys with all the right boxes ticked. If you were privately educated and went to Oxbridge, either keep quiet about it, make wry, self-deprecating excuses, or say things like “at least at college you could meet real people for the first time”.

Notwithstanding the previous paragraph, always try to write for right-wing newspapers and magazines instead of left-wing ones. The former pay better, do so on time, tend not to muck you about editorially and give better parties.

If possible, aim for American ditto, as they pay better still. A book review for The Times pays £300; its equivalent in the Wall Street Journal will net you $1,000.

Avoid the higher education system. A plague rat will do you more good. Don’t accept invitations to speak at universities or contribute to volumes edited by academics. You might not get paid, and if you do then the administrative hoops involved are simply not worth jumping through. On the other hand, if offered a job teaching creative writing at the University of Uttoxeter, accept: it could subsidise your writing career for a couple of decades.

A slight disadvantage is that you will have to teach creative writing students.

Don’t try to write novels. At any rate, not literary novels, which as a genre are dead in the water. Other categories now best avoided are literary biography, which publishers have now decided is a no-go area, and cultural criticism. “Nature writing” probably has another five years.

The trendy quadrant at the moment is memoir, so if your career so far can boast the slightest deviation from the norm — a life-threatening medical condition, say, or a particularly fraught upbringing — then get in quick. Beyond that, it’s going to have to be cosy crime or ideologically acceptable (i.e. “progressive”) social history.

Keep a diary. The muse is a fickle mistress. In 30 years’ time you will probably be desperate for something to publish: a record of your formative years, full of accounts of famous people you did, or didn’t talk to, at parties may be invaluable.

Naturally, exaggerate everything you said or did and take comfort from the fact that by the time the thing appears most of the people mentioned in it will be dead and unable to complain about some of your more exalted flights (“My night of passion with Salman”/ “my drug-bust with Will Self” etc.)

Never neglect free money. Always register your books for Public Lending Right and subscribe to the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society. It doesn’t cost anything and the proceeds will probably keep you in stationery for the best part of a year.

It’s a glamour profession. Despite the feeble remuneration, the incidental setbacks and the titanic egos at large in it, the literary life still has its charms — even here in an age of wall-to-wall philistinism.

Which would you sooner be: a stroller along the Grub Street boulevards or a chartered accountant? An habitué of the Times Literary Supplement or a loss-adjuster? Assuming that your replies fall into the former categories, all the Secret Author can do is wish you luck.