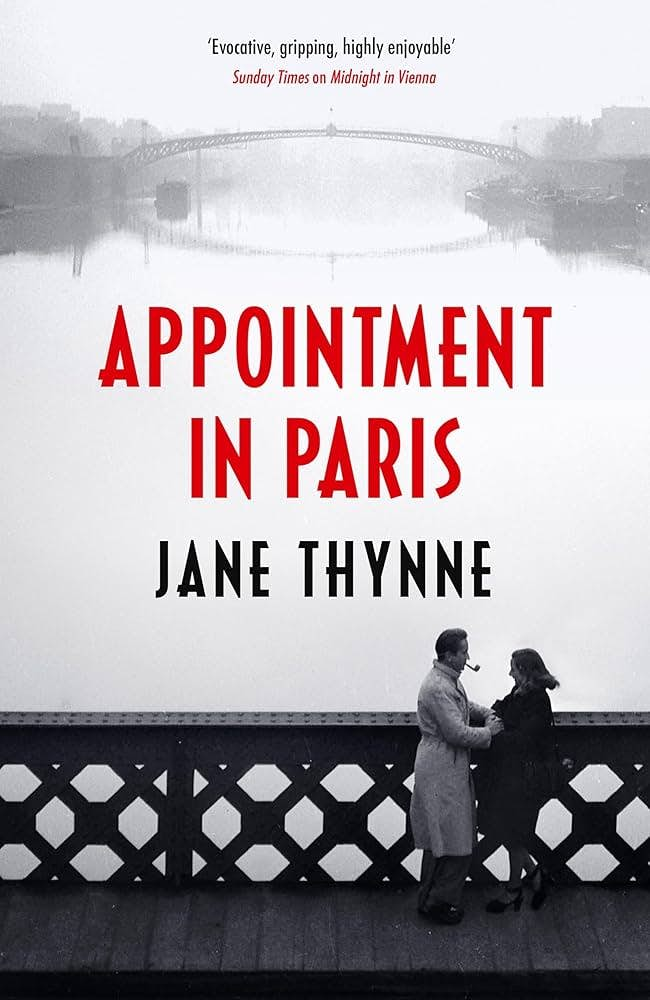

The novel for the month is Jane Thynne’s Appointment in Paris (Quercus, 2025, £20), the sequel to her Midnight in Vienna. Set in April-May 1940, this again provides the pair of Harry Fox and Stella Fry who are instructed to track down the disappearance of one of the listeners from Trent Park, which was, indeed, a base for the Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre where the conversations of German prisoners were secretly recorded and then transcribed in order to gain information. The disappearance occurs on the same night as the body of a shot German prisoner is found in the grounds. The cause of the killing is of interest but so, even more, is the question whether the listener has betrayed Trent Park. This is an excellent account with plenty of “real” characters, from Noel Coward to Churchill, Ian Fleming to Canaris, Maxwell Knight to Philip Sassoon; but the story is very grounded and focuses on a hunt for German spies, the world of German emigres, who provide many of the listeners, the miseries of rationing, the complexities of human relationships (which are handled very well), wartime sex, and the Fall of France. This is not a plot that, after the initial murder, focuses on killings, but one where relationships are to the fore. It is extremely successful. More please.

The rush of books appearing for the Xmas lists offers a mass of predictability, but also valuable quality, some of which is a matter of new editions. Penguin’s excellent series of Elmore Leonard reprints continues with Cat Chaser (1982; 2025; £9.99), which underlines the skill of this most versatile of writers with a Florida start and a Dominican Republic continuation. The atmosphere is classic Leonard, with deceit and death both handled very well. The characters are also classic: “the man’s life was in cardboard boxes he carried from one motel to another”. There are lots of well-observed details: “the warm underwater glow of the swimming pool”. “He told himself not to argue with himself; he was one of the few friends he had. He didn’t care for what he was doing right now. It was like going to the dentist when you were in love with his nurse, but it was still going to the dentist” … “Nolen was pathetic trying hard to be tragic” … “I never throw up, George. I value my nutrition” … “The surf came roaring in making a spectacle of itself.” Mastery in and of prose.

A different revisiting is Riverrun’s new edition (2025, £10.99) of Eoin McNamee’s Resurrection Man (1994) which follows their very welcome publication of his The Bureau, reviewed in an earlier issue. Again we are in Northern Ireland in the Troubles, with a retrospective that lends a perspective. There is “a cordite hum” in the air that is the backdrop to Victor’s murderous trajectory. There is a strong sense of place, including its danger: due to sectarian killers, “Your address was a thing to be guarded as if the words themselves possesses secret talismanic properties.” Still a very powerful and impressive book.

I referred in my last round-up to the latest Tom Mead book, which has led me to revisit his excellent Death and the Conjuror (2022; Head of Zeus, £9.99), a Joseph Spector story set in 1936 which is very clearly modelled on the Carter Dickson/John Dickson Carr impossible crimes, locked room stories. Mead does so with enormous success, although I wonder where one of the characters gets his money from. Works very well, with excellent characters, a first-rate plot, and an attractive prose style and use of words.

See also Mead’s The Murder Wheel (2023; Head of Zeus, £9.99), which offers three apparently impossible crimes: “Even the most elementary logic dictates that a killer does not adhere the weapon to his own hand, seal himself in the room with his victim, and then knock himself unconscious.” Joseph Spector to the rescue: “The fact is a body was infiltrated into one of the cabinets. Ipso facto, it’s not impossible. We must alter our perception of the whole event…. I can spot an inconsistency like no man on earth.” A Ferris wheel, a stage crate for a live magicians’ show, and a locked dressing room, the latter two in London’s well-realised Pomegranate Theatre in 1938, all provide the settings for murder, and this novel is a triumph of skill in puzzles and revelations. Mead sets himself high standards, and reaches them.

Disclosing the plot, or at least too much of it, is one of the reasons I dislike the reviews in the Times [of London, for Americans]. What, after all, is the point of reading a story if much has already been disclosed, and notably that which is not in the opener. It is striking that such a practice is especially the case with reviewers who lack the ambition or ability to comment on writing skill.

This leaves me with a problem in reviewing Jo Jakeman’s Cornish-set The Vanishing Act (Constable, 2025, £21.99), for the inside flap gives away far too much of the plot. As a result, the slow-burn set-up of the early stages of the novel is revealed. So, do not read the flap, or, if you do, savour anyway the skill with which the character, contexts and predicament of Eloise Ford is depicted as she reacts to the news of the discovery of the remains of the long-disappeared Elizabeth King. Written with wit as well as understanding:

Edward was mistaken about her wanting to be perfect. It was never about perfection. It was about safety. All her life was about staying safe, staying in control and creating order from the chaos. It was the only way she could breathe freely … incredibly tiring.

Dark Horse (Zaffre, 2025, £20) is the first I have read by Felix Francis, the much-published son of Dick Francis. Beginning with a race at Cheltenham, this is an easy read in which a heroine jockey is pursued by her bullying ex. Multiple perspectives, a murder, good courtroom drama, a satisfying twist. A chip off the Old Block.

Susan Gilruth’s Death in Ambush. A Lost Christmas Murder Mystery (1952, British Library Crime Classics, 2025, £10.99), represents an opportunity to rediscover a forgotten author. Gilruth, the pen name of Susannah Hornsby-Wright (1911-92), published seven detective novels in 1951-63, but, despite two BBC radio adaptations, they are now very difficult to find. This then is pitch perfect for the series, and offers a witty seasonal tale set in the village of Staple Green where death by a stroke sets off a well-devised account. Murder is announced in the first paragraph. There is the background of the pressures of austerity Britain on traditional society, the narrator fearing her husband would have to serve in Korea and that she would become a widow and “should have to take a job” because “I wouldn’t be able to live on my pension, income tax being what it is”. Currency restrictions are in place and “the Empire’s going to the dogs”. As a sign of past standards of care, a flu epidemic keeps the GP busy in the evenings. Social introductions and visits are important in village society, and a retired judge, with “the blessing of parental disapproval”, opposes impecunious marriages for his children. Period charms include a glass of claret and a biscuit for morning guests. Shops cannot sell spirits without a licence. The elderly want sherry not cocktails. The doctor has a cook and a nanny, and the vicar a maid, but for several others, as a defining difference, “every night is the staff’s night out”. The houses are cold, and this is very much a Britain that is waiting for the changes of the 1950s, notably economic growth and consumerism. Differences also come elsewhere as in “… patients … paying ones … not the National Health crowd”. Corned-beef hash with gravy is on the menu, as is rabbit pie of which there is lots because there is shooting for the pot, as also with pheasant. There is rationing: “I can’t continue to batten on your rations at the rate of two meals a day”. Conversely, the detective drives a Lancia, went to Rugby and quotes Latin, and the socially-observant Vicar’s wife attends the Conservative fête. The arrival at the village of “the main electricity cable” is an excellent piece of news. There are the demographics of the age — “He must be well over sixty” and therefore totally past it — the gender relations, sexual tensions, and money as an inevitable issue, alongside cigarettes as a constant recourse. My ignorance but I had never hitherto read of “a pachydermatous approach”.

“The snow, an endless white murmuration against the ink-dark sky”, but also “like a swarm of angry bees”, is the background for F. [Flic] L. Everett’s Murder at Mistletoe Manor (Penguin, 2023, £9.99). Psycho this is not, for a North Yorkshire country hotel with snowed-in staff, guests and animals, offers a less threatening background for murder. Some nice writing. There is a concern with colour, as in “a window glows the colour of clear honey” and “a marble fireplace the shade of raw mince”. The background is a decaying Britain, with homelessness an issue, moth-eaten rugs and old sofas in the hotel, the wi-fi down, and a sense of being trapped in a BBC period drama. A woman described has “leathery, tanned cleavage”.

Set on a Zeppelin on the Recife-Rio stage of the Friedrichshafen to Rio journey in 1933, Samir Machado de Machado’s The Good Nazi (2023, Pushkin, 2025, £12.99) won the Best Entertainment Novel at Brazil’s Prêmio Jabuti literary award. The dramatic cover gives a misleading account of the actual murder, but an effective locked room mystery with a clear moral content, while a well-realised cast provides insight into the twisted psyche of fascists in a manner made relevant for today. Alongside a plot that is based on a crucial inversion and draws on the plight of homosexuals under the Nazis, the writing can be wry: “Faithful to the nationalist spirit of the time, the gastronomic experience offered by Zeppelin on board its airships was not the best of global cuisine but rather the best of German cuisine, which, we can safely say, no one ever accused of being light and refined, but to which all due respect must be given for having provoked in its people a persistent questioning of the meaning of existence, aiding the formation of many generations of great philosophers.”

Sarah Ward’s The Death Lesson (Canelo, 2025, £9.99) begins with the death from a citalopram overdose of a new maths teacher at Penbryn Hall, an internationally-famous, exclusive Welsh girls’ public [ie private] school, and the deployment of investigator Mallory Dawson, an ex-policewoman undercover as her successor, in order to see if this was an assisted suicide. The school provides a closed set with its tensions and secrets, and the Solstice Sisterhood becomes a sinister vortex, an old girls’ network of faith and malice, with a secret mastermind. To my mind, overwritten in both plot and details, but others may like it.

Harriet Fox’s The Women in the Shadows (HQ, 2025, £9.99), a feminist reading of the Jack the Ripper story focused on male cruelty and corruption, is weakened by predictability and poor writing.

An interesting perspective on detection is offered by the contributors to Great Unsolved Crimes (Hutchinson, 1934), some by retired detectives, many by detective novelists, including Francis Iles’ ‘Was Crippen a Murderer?’, F. Tennyson Jesse, R. Austin Freeman, J. Jefferson Farjeon, J.S. Fletcher, Sayers, Anthony Berkeley, Freeman Wills Crofts, Henry Wade, and Margaret Cole. Each is worth reading.

The visual is catered for most easily with the Netflix production of Richard Osman’s overrated novel The Thursday Murder Club. An excellent cast, a lovely setting, and attractive visuals, all to go with a ridiculous plot, but many will be pleased. More pleasure will be earned from rewatching Robert Altman’s Gosford Park, which I first saw when it came out in 2001. Set in 1932, the story is brilliant, the characterisation excellent, the solution ingenious, and very different to the standard assumptions of the detective fiction of the period other than with plentiful possible suspects. This is both black comedy and “cosy” in setting, but bittersweet in much of the content and not least in the relationships. Gosford Park is far more mature and accomplished than The Thursday Murder Club, as can be seen in plot, characterisation, humour or, for examples, the contrasting acting by Helen Mirren.

I have not seen a copy, but Simon Wessely strongly recommends Michael Shepherd’s Sherlock Holmes and the Case of Dr Freud (1985), the last public lecture the distinguished psychiatrist gave.

As a Xmas quiz, write a short story starting: “We’ve all done it of course, merged bottles in the kitchen. I did it last month with three in which there was olive oil. But how often has this led to a trial for manslaughter? It should of course have been murder.”

Jeremy Black’s relevant books include The Game Is Afoot: The Enduring World of Sherlock Holmes; In Pursuit of Poirot; The Age of Nightmare: The Gothic and British Culture, 1750-1900; and English Culture: From the 18th Century to the Present Day.