“Toby Wigmore. A Tory MP with big ears and a small penis.” We could have a quiz as to which of the following that comes from, and how the protagonist knows this. But, in the meanwhile, as an historian, it is a great pleasure anew to begin with an historical work, one yet again republished in the excellent British Library Crime Classics series. After the frenetic somewhat Gothic intensity of the Carter Dickson reviewed in last month’s piece, we have Anthony Berkeley’s Not To Be Taken. A Puzzle in Poison (£9.99), originally published in serial form in 1937-8 and in book form in 1938. This is lighter in style and the pace and tone in this Dorset village murder are of pre-lapsarian calm. There is a ridiculous and unnecessary German plot dimension, an antisemitic Austrian cook, and British Military Intelligence, but all can be ignored in a fair-play novel about a poisoning that included, in its serial form, a quiz-reward near to the end. The British Library Crime Classics edition includes as an appendix Berkeley’s report on the very many replies none of which was fully correct. The details of rural society will interest many and the interplay of characters is effective. A very agreeable read and an impressive solution.

The short-story collections published in the series are good summer reading but eclectic, as in Guilty Creatures. A Menagerie of Mysteries edited by Martin Edwards (2021, £9.99). The best is the last, Christianna Brand’s “The Hornet’s Nest,” in which “Cockie,” her frequent hero, Inspector Cockrill, solves a murder in which the hornets are irrelevant, but the solution entails complex interpersonal relations. Josephine Bell’s “Death in a Cage” involves the zoo, Doyle, Chesterton and Wallace are on form, H.C. Bailey provides the evidence of slug slime, Mary Fitt that from a kleptomaniac jackdaw, and the others contribute to a strong collection.

Classic reissues of a different, more varied type, were featured in the first thirty of Penguin’s Modern Classics Crime and Espionage series. Numbers 31-33 have followed, each by Elmore Leonard (1925-2013), which are to be the first three, each priced at £9.99, of 14 of his due for publication by Penguin, seven later this year, the centenary of his birth, with the others in 2026. The first three, Swag (1976), The Switch (1978) and Rum Punch (1992), each deal with the chaotic causes and nature of crime, its unpredictable course, and moral (in a form) outcomes. The setting is an America of the greying of the “Long Boom”, of motels, fast cars, aircraft, independent women, incessant fraud and episodic deadly violence. The law is a harsh backdrop, the police gun-toters of a different category. Race is both observed and an issue. Ex-boxers provide muscle. Detroit before the fall already has the wealth leached to the suburbs and some of the “auto plants” have shut down. By Rum Punch, the aftermath of Desert Storm has large-scale arms-smuggling as part of the plot. For all three novels, the prose is crisp, the stories short, the tightest of the three being The Switch. The focus is on plot not author, on action not word-painting. Perfect summer reads.

My “murder of the month” is Anna Bailey’s Our Last Wild Days (Doubleday/Penguin, 2025, £16.99), which is described as “Southern Gothic Brilliance”, although the setting is not some gloomy mansion haunted by the past (there is one reference to Wednesday Addams, but it is inconsequential), but, rather, the poverty of Assumption Parish, a waterlogged part of Cajun County in Southern Louisiana. That is a major part of the appeal of detective fiction, its ability to conjure up landscape and culture. I have stayed near Hammond in Tangipahoa Parish, but that has a different feel and culture, which is a reminder of the degree to which there is variety in what might seem similar to the casual glance. Writing beautifully, with a real feel for phrases and the colour of words, Anna Bailey captures life in the raw, literally so with the economy of alligator hunting, as well as the pervasive presence of old wounds and hurts. The cast includes some staples: corrupt cops, crusading newshounds, totally vicious and completely heartless motorcycle drug dealers, male callousness and cruelty, and female friendship; but, instead of taking over with familiarity if not formalism, these staples people a plot of insight and subtlety, all against the background of a landscape that is alive with the shifting of the waters, and the sounds and sights of a world on which the human grasp is less potent than the pollution that is all too present. Bailey manages to bring the mysteries of a living animalistic spirit world into the here and now of her plot. A real triumph of atmospheric writing.

Bailey’s skill throws unflattering light on an ambitious debut novel, Sash Bischoff’s Sweet Fury (Penguin/Bantam, 2025, £16.99), which seeks to take F. Scott Fitzgerald into a modern age in which toxic masculinity can be blowtorched by female empowerment. Set in a world of self-regarding great opulence in and near New York, this is a very cleverly-plotted revenge drama albeit one weakened by standard conceits, as in vicious secret Ivy social societies. More serious is the writing, alternatively pedestrian, as in “The room was still, its collective breath suspended. Then, almost imperceptibly, Kurt nodded,” and OTT:

… trapped behind a wall of glass in a silent, seismic horror. Outside, dawn is just beginning its purl, the sky over the Hudson a blooming bruise, skin of the water slate to silver, fingers of fog curling in. The world a milky calm, still unmarred by the carnage within … she grips the mask with both her hands — glint of gilded armor in the dark.

Possibly this is inexperience on Bischoff’s part or a lack of help from the many she ecstatically thanks in the acknowledgements. What is a “plot doctor,” and by the way Sash, if everyone is fantastic, then no-one is anything. I doubt she will pay any attention, doubtless I am a toxic male, and her “friends”, will rally round, but Bischoff needs to read Bailey to see how to write well, including about toxic masculinity.

A different view of New York, one that is more personal, whimsical and yet also psychologically realistic, is offered by Daniel Aleman’s I Might Be In Trouble (Grand Central, 2024; Orion, 2025, £9.99) in which the world of homosexual sex takes the narrator into a one-night stand that ends with a dead body in bed. A madcap attempt to move the lad to a less compromising place offers a frenetic energy that in the second half becomes more of a psychological account by and of the narrator. Works well.

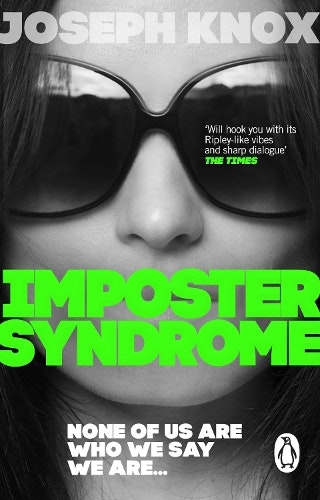

With the echo of Patricia Highsmith far less overt than Bischoff’s of Fitzgerald, and with the writing style far more pared down and fit for purpose, Joseph Knox’s Imposter Syndrome (Doubleday, 2024, Penguin, 2025, £9.99) provides the standard Ripley ingredients of impersonation, dysfunctional families, and great wealth, but, in place of Mediterranean sunlight and shadows, we have a contemporary London of smooth and deadly enforcers, ex-Special Forces goons, exploitation via social media, matter-of-fact murders, a dangerous “Tube” of watchers and pushers, smart Chelsea, and newbuild blocks, the police without consequence, all linked by the disposal of others, whether prominent or “Life’s bit-players. Those small parts and background roles. People who only get one or two lines.” There is a madness in which prestige and self-regard become deadly megalomania. The resolve might have been anticipated, at least in part, but, although very frenetic, the plot works well and Knox has an assured style as he takes his failed con-artist Lynch, arriving broke by Eurostar, into the identity of the long-disappeared Heydon Pierce, and then has him try to navigate his way round the frauds and murders of others. Excellent. Even the Athenaeum provides a setting.

Matthew Sullivan’s Midnight in Soap Lake (Harper Collins, 2025, £20) takes us to rural Washington State today and a conspiracy linked to small town secrets and a sinister bogeyman in the shape of TreeTop. This is depressing in the misery of the life of the poor in a “godforsaken town”, effective in the account as of women being misused, and possibly a parable about poor Whites being exploited by a conspiracy.

A very different setting is offered in David Reynolds’ The Lady in the Park (Muswell, 2025, £10.99) in which the discovery of a badly injured Caroline Swann in a London park launches a murder investigation in which the police are aided by a former member turned PI, Jim Domino, as well as his six-year-old grandson, Danny. Cue lots of reflections on modern British society and social norms in a plot that ranges to include organised crime, people-trafficking, dog-smuggling and police dynamics. A relaxed pace and easy writing as well as reading with plenty of description. An attractive summer read.

Beginning with an unfortunate text message to a large group of neighbours, Andrea Mara’s It Should Have Been You (Bantam, 2025, £16.99) spins into four killings and a spate of near-killings. The setting, suburban Dublin, is handled well as is the characterisation. The book really is a page-turner and with great pace and wonderful twists. But plot alone is not the key here, for the technique is also excellent: frequent shifts of focus between the narrators combined in a series of short punchy sections that deliver repeated new perspectives and take the plot forward. Excellent.

A different Ireland is on display in Andrea Carter’s There Came A-Tapping (Constable, 2025, £22.00), the account of a disappearance, that of film director, Rory, with the story told from the perspective of his partner, Allie, who takes refuge in the west of Ireland in Raven Cottage in the Slieve Bloom mountains. The world is ably realised by Carter who brings in a backstory of spiritualism, ravens, the haunted character of cottage and grounds, and the rivalries among the villagers. There is also the perspective of Suzanne, a police constable who tracks down part of the story of conspiracy and fraud. A very accomplished novel.

Another very different setting is offered by Jurica Pavičić’s excellent Red Water (Zagreb, 2017, English edition, Bitter Lemon Press, 2025, £9.99), a work that won a number of French prizes in 2021-2. 17-year-old Silva Vela disappears from her small Croatian hometown in 1989 after a party followed by sex. Her murder is suspected and this is skilfully traced through the complex dynamics of her hometown. Unexpectedly, her departure by bus from Split is eventually revealed which leads her twin brother, Mate, on a long search for her, one that by 2017 has thrown up many unexpected turns and shone a light on place, people and change, not least a seaside of wind and a deceptive opening from a world mentally closed but assailed by time. Ethnic tension, drugs, greed for land, and police rivalries all play a role, as does chance. The story is stretched through the transformative changes of revolution and war from 1989, with characters thrown together or apart by the changes and then seeking to make their way in the new-old society. Very ably written, for example, in Adrijan’s account of the ultimately explosive invasion of Bosnia in 1995, or of Gorki, a well-connected policeman turned agent for Irish land speculators, as in 2004 he comes up against the determination of the elderly to retain family plots. More memorable for its psychological insights, moral weight, and Tolstoyian quality (without the length). This is the only one of his nine novels I have read. His work deserves translation.

Diane Jeffrey’s The Crime Writer (HarperCollins, 2025, £9.99) is a very successful who-did-it-and-why, set in north Devon, about the disappearance of a jogger in 2019, and the possible guilt of her husband, a crime writer. The last is not the key theme which is somewhat misrepresented on the cover catch-phrase “He plots perfect murders. Did he commit one?” In 2024, the discovery of human bones revives the puzzle, landing one character in prison: “It’s a shame they don’t let you cook … ”, “Oh, the sex offenders do the cooking.” The writing is accomplished and the story works very well.

Graeme Macrae Burnet is new to me, but his A Case of Matricide (Contraband/Saraband, 2024; £14.99) can be read without the first two in the series, the Disappearance of Adèle Bedeau (2014) and L’Accident on the A35 (2017). The conceit is that of the translation of the work of an imaginary French novelist, Raymond Brunet (1953-92), and he is given a considerable critical backstory. Set in southern Alsace, this is a “What is going on?”, a “Why done it?,” an insightful psychological portrait of Chief Inspector Georges Gorski, and an account of the trials of provincial life which include emptiness, boredom, drunkenness, and local government corruption, the last more potent than the law that Gorski seeks to hold in place. Good writing, an excellent observation of character, a Simenon-like pace and a novel that is both very good and pleasantly short.

I was wrong about Neil Lancaster’s When Shadows Fall (Harper Collins, 2025, £16.99). Serial killers are not my thing, and a protagonist (and an author as well) who are action heroes are not either. I started thinking of reviewer’s duty, but I was wrong. This is a really good thriller. Blonde women climbing alone in the Scottish Highlands are falling to deaths treated as accidents, but it becomes apparent that there is a pattern. This leads to a hunt for a killer who is a pace ahead due to a police-source, and we move into a complex and well-driven thriller in which the cerebral level is amply presented in tracking down a conspiracy with plentiful use of code-breaking. Whenever the plot appears clear, there is an effective and credible shift, while the cast is well-realised as is their dialogue. This is not an example of Scottish noir in which there is incomprehensible Glaswegian argot or a ridiculous morass of Gaelic mythology. Tracking down the why, who and how of the conspiracy is done well and makes this the proverbial page-turner. I was glad to be proven wrong.

Another successful instance of recent Scottish detective fiction is provided in the Shona Oliver series by Lynne McEwan which is published by Canelo. The fifth, A Troubled Tide (2025, £9.99), is set on the Scottish side of Solway with the death of a policewoman competing in a triathlon, a death that moves from drowning via drugs to a puncture wound suggesting murder. Despite split infinitives, the style and language are reasonably calm: this is not a mean streets set in a dystopia., but there are gangs from Carlisle to Dumfries, drugs aplenty, sexual tension, the cruelties of men to women, police uncertainties, and a reality of betrayals to create a very different but still unsettling dystopia.

A different geographical context is provided by Simon McCleave in The Snowdonia Killings (Canelo, 2025, £9.99). Originally published in 2019 by Stamford Publishing, this is the first of the DI Ruth Hunter series which currently has 21 titles. McCleave has a background in television and film, notably as a script editor and writer, and that shows in the terse style of his writing, which is plot-driven and spare, although there is room for a full development of his characters and for an engagement with the landscape. The protagonists are Hunter, a bereft lesbian detective from the Met, exhausted by the brutality of London crime and the personalities of too many of its police, who has chosen to relocate to North Wales, and Nick, her talented local assistant who has a very serious drinking problem. The murder of an unpopular deputy headteacher with a spiral symbol carved into her skin launches us into a convincing police procedural with impressive plot, and more killing to come. Other themes include racism, suicide, sexual desire, and the pressures on the police. On the basis of this one, the series looks good, and well done on a short Acknowledgements that totally avoids the exuberant narcissism of so many from the genre.

Rather than historic, Taku Ashibe’s Murder in the House of Omari (Pushkin Vertigo, 2025, £9.99) is a historical novel, the translation of a 2021 work by a master of the modern Japanese detective novel. His plot focuses on deadly family dynamics in 1945 that look back to marital and inheritance issues from the start of the century, with an escalating pace as World War Two, “the land of the dead”, becomes more destructive, hitting hard the Osaka mercantile families. The “city’s past” might be forgotten by “the locals”, but that is not the case for the cosmetic-manufacturing House of Omari, which is in decline. There is a pervasive grip on imagination and plot, of older detective novels, Japanese and other, and that in a wartime context in which such novels are regarded as unpatriotic and against national policy. Shigehiko Omari is trying to write one but “so many things were vanishing day by day, and all that was left was a series of present moments”. The plot resolutions were not a surprise, unlike the cause which was.

Kelly Gardiner and Sharmini Kumar’s Miss Caroline Bingley, Private Detective (HQ, 2025, £9.99) is beautifully written and a fine homage to the world of Austen, albeit more bracing in the plot-challenges than her novels, while the theme and persona of an independent woman is written with some modern shades that would have surprised the great novelist, not least the theme of Indians in London, as well as a range of milieux including the rougher parts of the East End and the Docks. This is different to P.D. James’ Pemberley, but not the worse for that. A highly entertaining read.

A different type of “cosiness” is offered by Murder on Bluebell Hill ((HQ, 2025, £9.99), the fourth of Jane Bettany’s Violet Brewer mysteries. Set in a rural Peak District that is far more prosperous than Anna Bailey’s Louisiana, Matthew Sullivan’s Washington State, or Andrea Carter’s rural Ireland, this presents a world of competing tearooms with the death of the owner of one being rapidly revealed as murder, and Violet Brewster, a well-meaning and pleasant busybody, doing a Miss Marple on the potential culprits. Comfortable, well-written, a good pace, and a satisfying plot. A good holiday read.

If bloodthirsty monsters and serial killers are to your taste, then Helen Phifer’s Lake District-set The Lake House (HQ, 2025, £9.99) will suit you, but I am not into “huge, scary, black claws”. Like the “blue book” NeoGothic works of the 1820s and 1830s.

The death of Peter Lovesey has brought to end a talented career of publication in this genre from 1970 to 2024. For sheer exuberance on a bad day, read The False Inspector Dew (1982), which is much more accomplished than Stoppard’s Real Inspector Hound. Lovesey (1936-2025) wrote across the field of detective fiction, but his Sergeant Cribb novels (1970-8) are particularly successful. Aside from his 43 novels, there are also six short story collections, two edited anthologies, and four non-fiction books. An author able to write well from Golden Age to modern-day.