The idea of having babies in space might sound like the plot from the latest science fiction blockbuster.

But as we enter a ‘new era of exploration’, scientists say we’re on the cusp of it becoming reality.

In a new paper, a group of international experts claims discussions about reproductive health beyond the bounds of planet Earth must become a top priority.

They claim the ‘question of human fertility in space is no longer theoretical but urgently practical’ as humanity turns its attention to long–duration missions, such as those to Mars.

According to the experts, not enough is known about male or female fertility in space, nor about the development of embryos and then babies in zero-gravity.

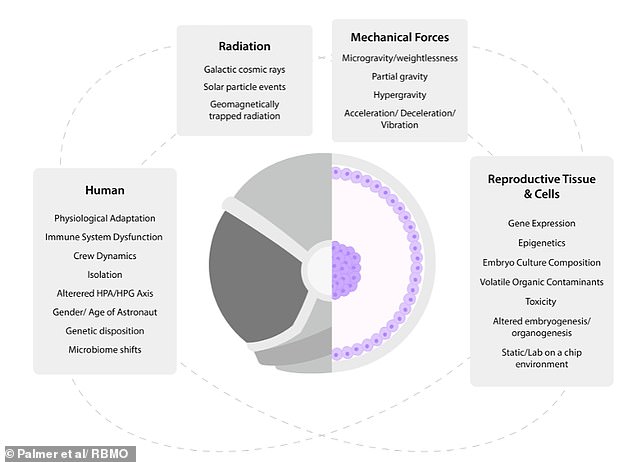

Worryingly, they predict space radiation could leave newborns with developmental abnormalities so extreme that their bodies may be ill–suited to ever return to Earth’s gravity.

‘As human presence in space expands, reproductive health can no longer remain a policy blind spot,’ Dr Fathi Karouia, senior author of the study and a research scientist at NASA, said.

‘International collaboration is urgently needed to close critical knowledge gaps and establish ethical guidelines that protect both professional and private astronauts – and ultimately safeguard humanity as we move toward a sustained presence beyond Earth.’

Reproduction in space is not a easy as in Hollywood movies such as 1979 Bond film Moonraker make out

As we enter a ‘new era of exploration’, scientists say we’re on the cusp of babies in space becoming a reality

The combination of low gravity and high radiation would exert unknown effects on developing human embryos (file image)

NASA astronaut Peggy Whitson pauses for a photo while working inside the Microgravity Sciences Glovebox. Experts say various pieces of apparatus used in biological experiments on the ISS are comparable to equipment found in an IVF laboratory on Earth

The nine authors of the paper include experts in reproductive health, aerospace medicine and bioethics.

They argue that action is urgently needed as the window for setting boundaries around reproduction in space is rapidly closing.

‘Despite over 65 years of human spaceflight activities, little is known of the impact of the space environment on the human reproductive systems during long–duration missions,’ the review, published in the journal Reproductive Biomedicine Online, reads.

‘Extended time in space poses potential hazards to the reproductive function of female and male astronauts, including exposure to cosmic radiation, altered gravity, psychological and physical stress, and disruption to circadian rhythm.’

The team said current evidence suggests short–term missions do not significantly alter male fertility, as two of the Apollo astronauts have fathered children since their time in space.

A mission to Mars, on the other hand, would involve much higher levels of radiation exposure – which could ‘potentially compromise testicular function, future fertility and the health of offspring’.

Meanwhile, data available from 40 female astronauts indicates that both pregnancy rates and related complications are comparable with those seen in age–matched women on Earth.

However, as longer–duration missions become more common for women, it is ‘crucial to understand the effects of spaceflight on reproductive endocrinology, hormones, pregnancy and assisted reproductive technology beyond Earth,’ the team said.

Though the idea of having babies in space might sound like the plot from the latest science fiction blockbuster, a new paper claims discussions about reproductive health beyond the bounds of planet Earth must become a top priority

Passengers kiss aboard a flight that simulates the weightlessness of space. Zero–gravity intimacy is just one of the challenges facing extraterrestrial reproduction

The hazards and environmental factors that could affect humans and embryos in space, including microgravity and toxicity

In their paper, the experts said long–term space exploration may involve transporting eggs, sperm or embryos from Earth to other worlds.

One such method could involve freeze–drying eggs or sperm for later use in IVF.

‘Various pieces of apparatus employed in space and used in biological experiments on the International Space Station are comparable to equipment found in an IVF laboratory on Earth,’ they added.

They argue that both spaceflight and IVF have evolved along a similar timeline.

And they said IVF is ‘poised to play a critical role in the future of human space exploration’.

‘More than 50 years ago two scientific breakthroughs reshaped what was thought biologically and physically possible – the first Moon landing and the first proof of human fertilisation in vitro,’ clinical embryologist Giles Palmer, from the International IVF Initiative Inc said.

‘Now, more than half a century later, we argue in this report that these once–separate revolutions are colliding in a practical and underexplored reality.

‘Space is becoming a workplace and a destination, while assisted reproductive technologies have become highly advanced, increasingly automated and widely accessible.’

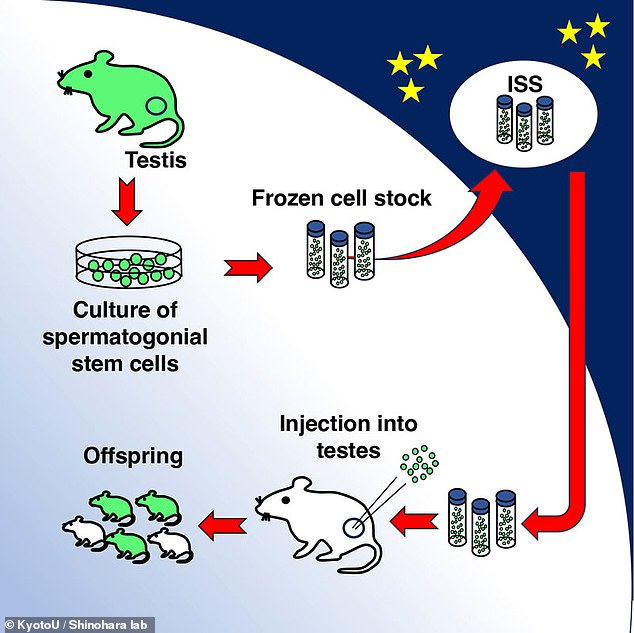

Previous studies found stem cells from mice cryopreserved on the International Space Station for six months have produced healthy offspring

The team said the Moon remains the most immediate and practical testing ground for understanding how life functions in reduced gravity.

‘It could act as a natural springboard for controlled, ethical and carefully designed reproductive studies that could, one day, make sustained life on Mars possible,’ they said.

Last year, researchers from Kyoto University showed that mouse egg and sperm cells could survive in space and go on to produce healthy offspring.

Meanwhile, Dutch Biotech startup Spaceborn United have launched the first miniature lab for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and embryo processes into orbit.

‘Humanity is steadily approaching the era of routine space travel, with visions of lunar and Martian settlements shifting from science fiction to commercial ambition,’ the researchers said.

‘As space missions become longer and more diverse in crew composition, shifting from weeks to months, and eventually years, understanding the risks to fertility and reproduction has become not only relevant but essential.’