This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

In May 2020, James Payne started a YouTube channel called “Great Art Explained”. The first video he posted, an introduction to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, has been viewed over 4.6 million times. “Great Art Explained” now has 1.75 million subscribers. Watch the Mona Lisa video, and you will understand why: Payne has an engagingly unpretentious manner; his technical insights can prove illuminating even to professional artists and historians of art.

Payne has no formal training in art history. Instead, he studied fine art as a mature student, then worked as a curator and film editor. He learned the hard way how to capture an audience’s attention, having spent his twenties taking groups of American teenagers through the great museums of France and Italy.

Payne’s only serious competitor as a YouTube educator in art history is Fr Patrick van der Vorst, a former director at Sotheby’s who has such a gentle manner that you forget how frighteningly erudite he is about painting. Yet Payne seems to be addressing a very different online audience — one that wants to learn about Old Master paintings whilst remaining sceptical about the value of Christian culture and of the European civilisation in which the Old Masters arose.

“Great Art Explained” has been so successful that Payne last year created a second YouTube channel, “Great Books Explained”, taking viewers through works including Alice In Wonderland, Moby Dick, The Lord of the Rings, James Joyce’s Ulysses and George Orwell’s 1984, each in 15 or 20 minutes. He also has 20-minute introductions to Shakespeare and the Bible.

Although Payne is clearly a voracious reader, he cannot always figure out how to present his subjects to beginners. Also, the illustrative photos, film footage and background music in the “Great Books Explained” videos often seem arbitrary and anachronistic.

Evidently Payne has bitten off more than he can chew. Then again, he creates his YouTube videos without researchers, interns or a film crew. When was the last time a well-funded BBC produced anything half as good as even the weakest of Payne’s videos?

“Great Books Explained” raises the question of what Payne means by “great”. It isn’t always clear from the range of books he discusses. His selection of artworks on the “Great Art Explained” channel is similarly unwieldy, to the point where it risks incoherence.

“Great” art is taken to include everything from Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces such as Michelangelo’s David, Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne to controversial 20th century pieces like Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe prints, Man Ray’s Surrealist works and Spiral Jetty, a 1970 piece of “land art” on the shores of the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Such an elastic application of “great” might not faze a connoisseur, but to a layman it is all terribly confusing.

Even artworks as widely beloved as Claude Monet’s series of Water Lilies paintings (1897–1926) seem to the uninformed viewer to be less impressive than the large-scale accomplishments of ambitious Renaissance artists, pretty though the Water Lilies undoubtedly are.

There is no question that all of Monet’s work is inferior, at least in a technical sense, to an intellectual and spiritual tour de force such as Raphael’s School of Athens fresco in the Vatican. How can we honestly equate Monet to Raphael as “great” — and why should we even try? These are real, not rhetorical, questions that demand at least a stab at an answer.

To take two of Payne’s “great” paintings from the same historical period: Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa was completed in 1819; Francisco Goya’s haunting series of 14 so-called Black Paintings was finished by 1823. Géricault’s picture is a piece of campy, melodramatic agitprop that now seems comically dated, whereas all of Goya’s Black Paintings have the vividity and freshness of a recent nightmare.

How could Payne place a histrionic also-ran like Géricault in the same class as Goya? Payne has now published a book to articulate his vision more clearly.

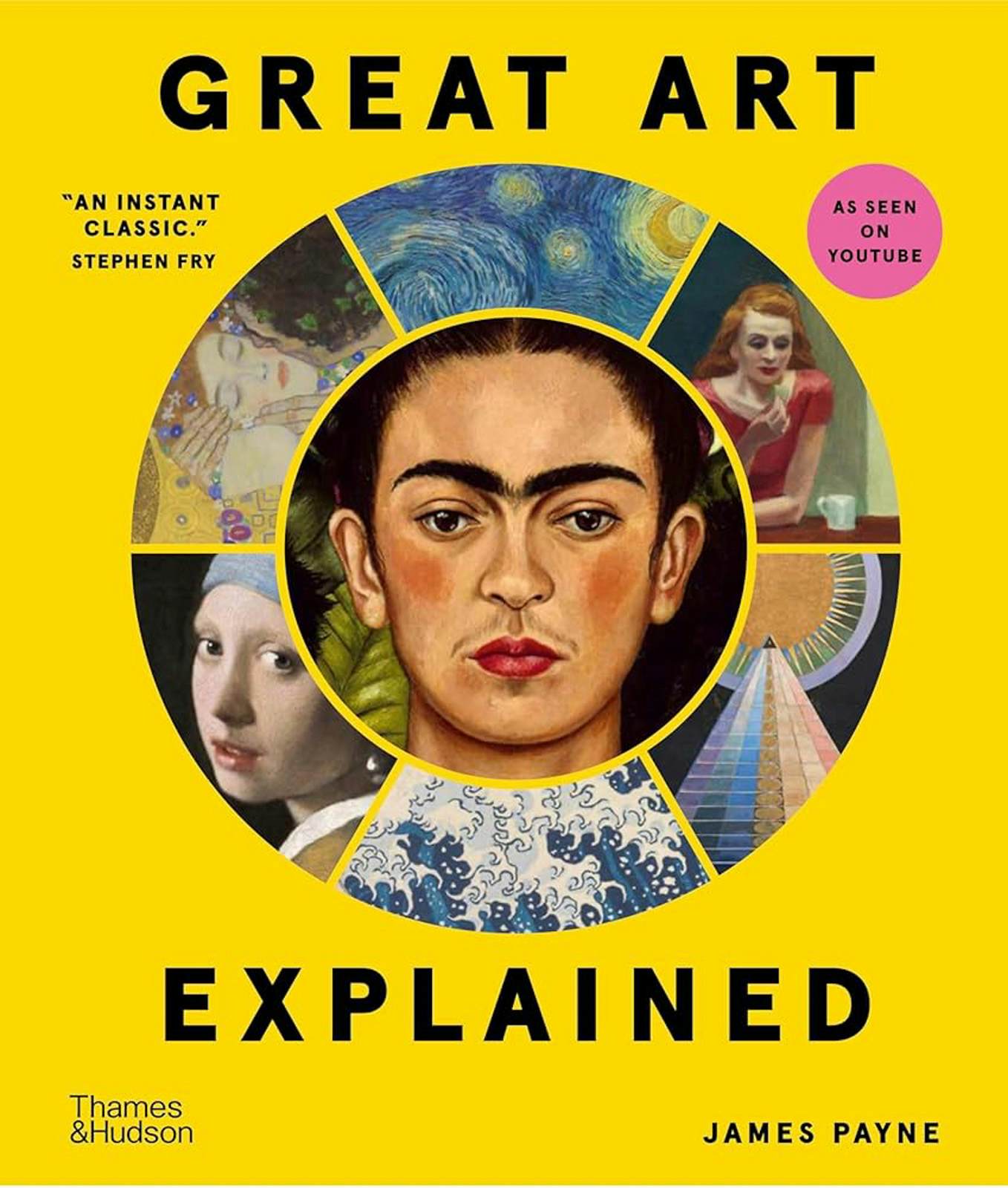

Great Art Explained takes the reader through 30 works of art, around half of which are well known, and two thirds of which are by artists who are household names, such as Hieronymus Bosch (another painter of nightmares) and the Japanese printmaker Hokusai, whose 1831 woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa is one of a few non-Western works of art to have become almost as iconic as the Mona Lisa.

Payne also exposes the reader to 20th and 21st century artists whose work is unfamiliar even to most art lovers, such as Hilma af Klint, a Swedish vegetarian and proto-feminist who created abstract paintings as part of her exploration of crank spiritual practices.

Another of Payne’s discoveries is Suzanne Veladon, who was both model and mistress to several Impressionist painters in the 1880s, and later became a painter in her own right. She seems more widely appreciated by feminist art historians than museum-goers, but her work was championed by the prickliest major artist of his time, Edgar Degas, whose paintings are strangely absent from Great Art Explained.

For all his genius, Degas is often thought of as an uptight, embittered, reactionary misogynist, perhaps because that is precisely what he was. Even so, when it came to art, he focused on what was created, not the identity of the creator. Talent and vision mattered more to him than identitarian concerns. If only Payne had followed Degas’s example.

Too many of the selections in his book are based on identity politics. Payne may admire the work of Artemisia Gentileschi, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keefe, but even their best work seems derivative and second-rate compared to the efforts of their most important male contemporaries. Then again, to give voice to such an observation in public is to risk being scolded as a “misogynist”, even if no honest, fair-minded person can deny it.

Similar identitarian concerns are at play with all the non-white, non-European artists Payne includes (with the exception of Hokusai). Needless to say, Payne wants to avoid being slimed as a “racist”, or “misogynist”, or accused of being in the grip of some spurious “phobia”. Such accusations have real-world consequences, after all. But his timidity in the face of modern shaming rituals makes him less trustworthy as a guide than he ought to be. How can he teach us how to use our eyes when he shies away from stating visible truths?

If only Payne had chosen to take the reader by the hand and demonstrate the greatness of Rubens, Titian, Rembrandt and other Old Masters whose skill is self-evident only to those who have been taught how to look for it. His secret weapon as an educator is his knack for patiently demonstrating how art is created.

But in this book he does not even show us how to examine the work of Monet, one of his artistic heroes. Instead, he wastes too much space on attempting to interpret art, when this simply is not his strength.

Though Payne seems curious and open-minded about non-Western art, he is helplessly reliant on museum websites and elementary guides when trying to explain, for example, classical Chinese art. His discussion of Along the River During the Qingming Festival, the masterpiece of the Song dynasty painter Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145) is sloppily organised, and features too much irrelevant speculation. Also, there are too few high-resolution illustrations in this section, so that the reader often struggles to see what Payne is trying to describe. In general, Great Art Explained could have done with a more user-friendly layout.

Payne is clearly capable of so much more than this. His August 2025 video on the Viennese Expressionist painter Egon Schiele (1890–1918) is one of his finest to date: it demonstrates real growth and development as a filmmaker. Perhaps he would be better sticking to YouTube?