For eight centuries since his death, the Umbrian mountain town of Assisi has been synonymous with Saint Francis, the son of a rich merchant family who forsook a vast inheritance to live as a wandering preacher.

Making light of the arduously steep streets, pilgrims venture here from far and wide to pray beside his tomb in the basilica and visit landmarks such as the Sanctuary of Spoliation, where he swapped his fine clothes for a loincloth.

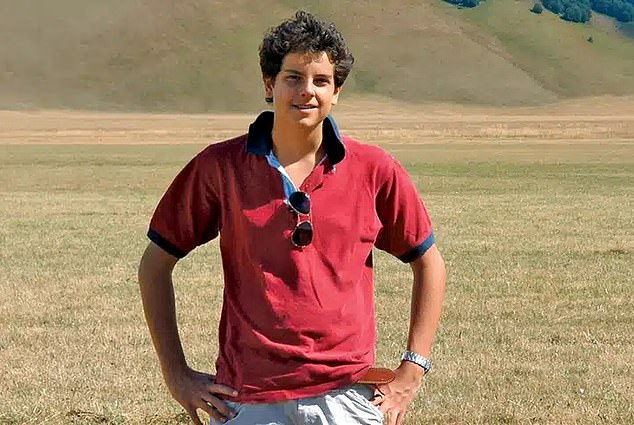

Yet the legendary Francis is Assisi’s biggest attraction no longer. His popularity has been surpassed by that of the new kid on the town’s cobbled blocks: London-born Carlo Acutis, a boy who lived for just 15 years – and this morning he will be canonised as the first ‘Millennial Saint’.

‘When I came here, maybe one or two thousand visitors would visit this square each year,’ the Archbishop of Assisi Domenico Sorrentino told me, gesturing towards the sanctuary’s courtyard.

‘Do you know how many came last year? A million or more. All sorts of people used to come and see Francis but a new, younger type are coming for Carlo. At a time when society has many problems, he is their compass.’

With his boyband good looks, Carlo has been called the Rock Star of Roman Catholicism, and the cleric doesn’t demur. ‘But my time is of The Beatles,’ he laughs, breaking into a chorus of Yellow Submarine.

Carlo’s body is exhibited in the Church of St Mary Major in a uniquely designed, glass-sided tomb, suspended in mid-air so that it appears to have been torn from the Earth and floating to Heaven. Exhumed 13 years after his death, his remains are said to have been miraculously undecomposed.

It only needed a touch of silicon to restore his handsome features, so we are told, and he even retained his tousled hair.

Carlo Acutis, who died of leukaemia in 2006 aged 15, will be canonised as the first ‘Millenial Saint’

The remains of Blessed Carlo Acutis lay in his tomb in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore

Acutis is said to have performed two miracles includes on a Brazilian boy Matheus Vianna (pictured)

Dressed for eternity in his weekend clothes – a designer tracksuit, blue jeans and Nike trainers – he looks like a Madame Tussauds waxwork of the teenage Harry Styles, and he appears to be smiling at the awed throngs who file past him, genuflecting, kissing the viewing window and posting scribbled prayers in a box beside him.

‘Carlo’s just so great!’ cooed Matilda Kalaga, 17, when I asked why she and her friends had made the long journey from Poland. ‘I relate to him because he was so normal. He was just like us really.’

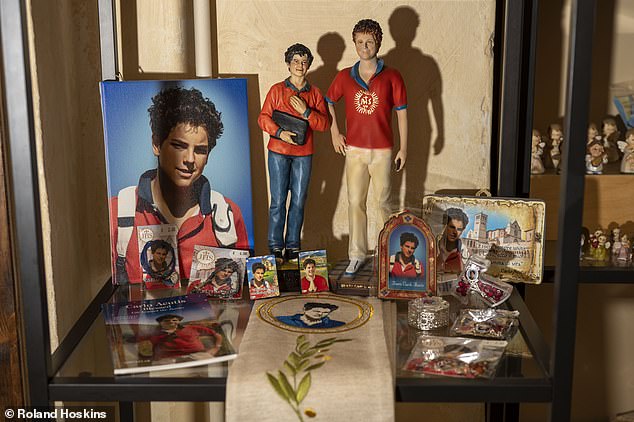

Ushered out of the church to make way for others in the long queue, her group headed for souvenir shops cashing in on the Carlo craze by selling his statuettes (the largest of which costs 55 euros), fridge magnets, bags, broaches and even Christmas tree baubles bearing his fresh face.

As British tour guide Gwen Wiseman, who shows pilgrims landmarks of his life, tells me breathlessly: ‘Carlo has made it cool to be Catholic again!’

It would seem so. However, inside the upper echelons of the Catholic church there are those who don’t share this unbridled enthusiasm for Sunday’s sainting ceremony, though it promises another electrifying Vatican spectacle six months after the theatrical funeral of Pope Francis.

For they contend that Carlo’s canonisation has been contrived, or at least fast-tracked, purely because the Catholic church is desperate to reconnect with young people, who deserted the pews in their millions in disgust over its covered-up sexual abuse scandals.

This argument is illustrated, they say, by two giant tapestries draped above the Pope yesterday when he appeared on the steps of St Peter’s basilica. One is a very modern colour portrait depicting the wholesome-looking Carlo, out on a hike in a crimson shirt. The other, copied from a century-old monochrome photograph, shows a far less famous youth who will also be made a saint on Sunday, Pier Giorgio Frassati.

The ‘heroic virtues’ that earned them the church’s highest honour will be recounted before a vast audience in St Peter’s Square (sure to include many Britons, since Carlo came into the world in London’s Portland Clinic where several royal babies have been born). And in many ways the stories of Carlo, who spent the early months of his life in a fine townhouse in Kensington, South London, and Turin-based Pier, are remarkably similar. Both were young, athletic and strikingly handsome, both undoubtedly led exemplary lives, helping the poor and disadvantaged. Both also hailed from wealthy families.

Carlo’s showcase achievement was a self-created website documenting more than 136 so-called Eucharistic miracles

Carlo Acutis (pictured) smiling at the camera while sporting an AC Milan home kit from the 1990s

His parents were secular Catholics but his unexplained pull to the church was such, his mother Antonia (pictured) told me, that from infancy he attended mass every day, taking communion at age seven

When Carlo was born, his father Andrea worked for Lazard, one of London’s oldest and most prestigious investment banks, and now heads a leading Italian insurance company. His mother Antonia was studying English before returning to Milan to join her family’s publishing firm.

Before devoting his life to good works, Pier was a member of Italy’s racy Alpine skiing set and his father Alfredo founded La Stampa, a cornerstone of the Italian press. Both men also died when tragically young: Carlo of leukaemia in 2006, when he was just 15, Pier Giorgio of polio in 1925, aged 24. As critics point out, however, it is here that their paths to sanctity sharply diverge.

As the antiquated tapestry image of Pier shows, it has taken the Vatican’s saint-making machine (officially known as the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints) eight decades to deem him worthy of canonisation – and his candidature was left in abeyance for several years pending an investigation into claims he kept the wrong company.

By contrast, Carlo’s cause was rushed through at a speed even a senior cleric championing his cause admits to have been ‘supersonic’. The race began just five years after his death and the investigation onto his saintly credentials was completed in only three years between 2013 and 2016.

Pope Francis beatified him – the penultimate stage before sainthood is conferred – in 2020 and by 2022 he was deemed suitable for canonisation. The whole process had taken just over a decade: such a relatively short time that it is almost unheard of.

The Vatican’s dusty files contain the names of scores of noble men and women who have been beatified without passing the final hurdle, some waiting for centuries.

Why has this callow teen leapfrogged the queue? Some senior traditionalists put this down to the Vatican’s quest for a ‘Gen Z Saint’ and with his pop idol looks,

Ordinary Joe personality and pioneering style of internet evangelism, Carlo perfectly fills the bill.

Carlo (pictured) was a devout Christian when he was alive and attended daily mass, taking cmmunion aged seven

Acutis, who has been referred to as ‘God’s Influencer,’ will become the first millennial saint when he is canonised in a ceremony during the Church’s Jubilee of Teenagers

Figurines of Blessed Carlo Acutis have been on sale in a souvenirs shop in Assisi where Acutis is on display

Among the gentler sceptics is veteran religious affairs writer Kenneth L Woodward, author of Making Saints, a searching inquiry into the Vatican’s arcane saint-creating process.

In his book, he describes how the so-called ‘exact science’ of filtering out truly deserving saints has been streamlined down the years. For centuries, each cause was forensically examined as in a courtroom trial, with a postulator championing the candidate’s cause and a Protector of the Faith (commonly called the ‘Devil’s Advocate’) probing for failings that might render them unsuitable for canonisation.

But in 1983, Pope John Paul II streamlined the procedure, doing away with the Devil’s Advocate and effectively placing both sides of the investigation into the postulator’s hands.

This has opened the floodgates for saint-making on an almost industrial scale.

During his 27-year papacy, John Paul canonised 482 saints, more than all the other popes in history. Pope Francis, who died in the same April week that he was due to canonise Carlo, almost doubled that number.

‘It wasn’t so many decades ago that you had to wait for 50 years just for a (potential saint’s) reputation to establish itself,’ Woodward told me. This ensured a candidate’s reputation for holiness was genuine and not a passing phase of ‘celebrity’.

But, he added, ‘here’s a guy [Carlo] whose reputation is built on something new, the internet, and it’s happening overnight.

‘I think it’s a new ballgame for the process and the people involved need to think very carefully about it. The enthusiasm of young people can quickly move on to other things.’

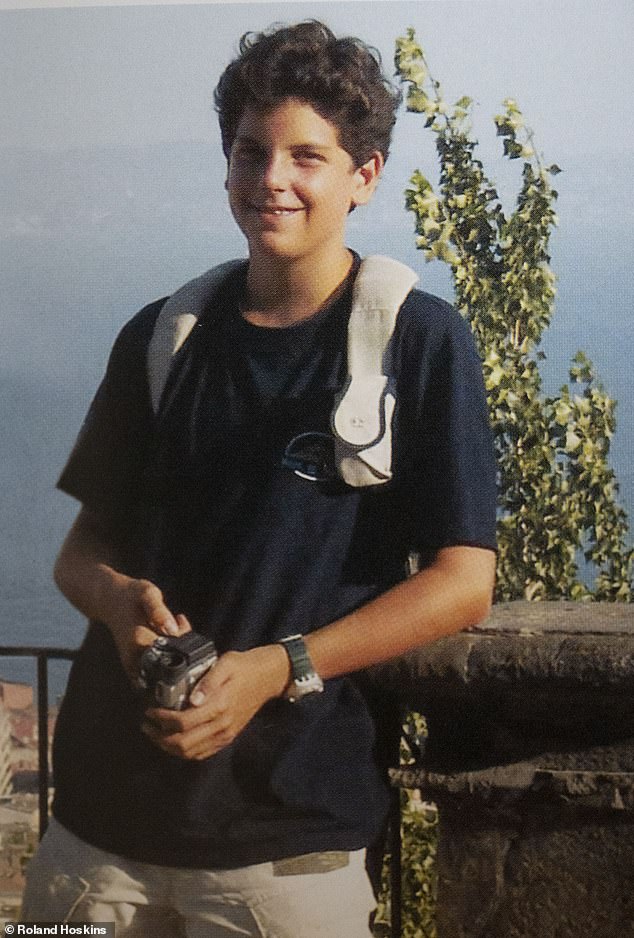

Carlo (pictured as a baby) was also an incredibly smart young boy, speaking his first word at three months, starting talking at five months, and writing at age four

Because of his affinity with St Francis, he was entombed in Assisi and soon their statues will also stand side-by-side in the town

Workers installed a tapestry on the facade of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican depicting an image of Carlo Acutis

The criticism of controversial Catholic scholar Andrea Grillo, liturgy professor at one of the Vatican’s pontifical universities, is stronger.

Carlo’s showcase achievement was a self-created website documenting more than 136 so-called Eucharistic miracles – unexplained events whereby, for example, ‘hosts’ such as wine and bread turn into blood or flesh.

In a blog that is angering Carlo’s supporters, however, Grillo claims the teenager’s interpretation of these historical occurrences was badly flawed because he was taught by ill-informed religious mentors.

‘The digital show he created online (about the miracles) is not good,’ he told me. ‘But I don’t blame him. I blame his teachers. At 14, he can’t have understood what he was writing unless he had someone older next to him.’

Grillo claimed one Milan postulator declined to champion Carlo’s cause before it was taken up by Nicola Gori, 59, who writes for the Vatican’s daily newspaper.

Gori calls Carlo ‘a pioneer’, the writer adding he was ‘immediately fascinated by the brevity of his life and the intensity of his spiritualty,’ as well as his ‘ability to engage his peers in this adventure’.

However, others whisper that he might never have been canonised, regardless of his achievements, if his rich family hadn’t footed much of the bill.

It is hard to calculate the cost of making someone a saint because it usually spans many generations and, as Woodward says in his book, ‘Vatican officials would rather talk about sex than money’. As long ago as 1975, though, one priest told The Wall Street Journal that it required ‘millions of dollars’. Another insider put it in the hundreds of thousands, factoring in professional fees for lawyers and doctors investigating the candidate’s life and purported miracles, transport and hotels, and the huge expense of staging the sainting ceremony itself.

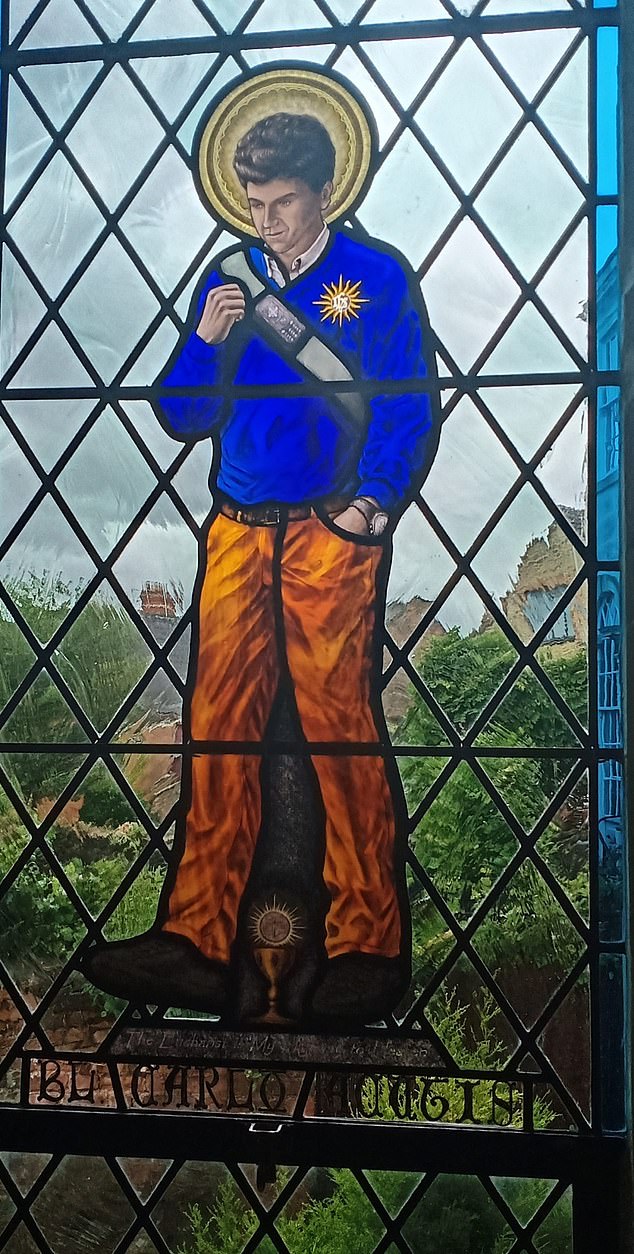

Picture shows a stained glass window created for the Blessed Carlo Acutis

Pilgrims queue to enter the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore church and to pay their respects at the tomb of the Blessed Carlo Acutis

Whether or not he merits a sainthood, no one I have come across when examining Carlo’s short life doubts that it was one of exemplary goodness and unfathomable occurrences.

His parents were secular Catholics but his unexplained pull to the church was such, his mother Antonia told me, that from infancy he attended mass every day, taking communion at age seven.

This assertion was confirmed to me by people in Assisi, birthplace of the 13th century Saint Francis, where the Acutis family had a holiday home.

‘At eight or nine, he started doing charity work,’ says Antonia (who describes Carlo as ‘virtually English’ by way of his birthplace and ancestry).

‘For example, serving meals in the local Mother Teresa house, healing street beggars, giving them food and advice.

‘Carlo was a friend of Jews, Muslims, everybody. In our area (an affluent Milan neighbourhood), many people from other continents worked in the houses and Carlo would stop and speak to them. He was very smart, very open.’

Her son’s Christian virtues were also evident at his private school, she says. He would defend the bullied, eschewed the drink and drugs to which some contemporaries succumbed and though he wasn’t good at every subject he became an IT whizz, always using his computer for good causes (as proved by the Vatican’s examination of his online search history).

But, surely, he must have had some teenage foibles? A fondness for fashionable clothes, or rock music, perhaps?

Pilgrims pray and pay their respects at the tomb of Blessed Carlo Acutis in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore and Sanctuary of the Renunciation in March

Acutis’s body has been encased in a wax layer moulded to look like his body prior to burial, allowing faithful to see Acutis as he lived in his tomb

His mother hisses the suggestion away. ‘Too busy’ doing good deeds, she says.

As for girls, his postulator Nicola Gori says the Virgin Mary was ‘the only woman in his life’.

Carlo’s former schoolfriends present a somewhat different picture. Federico Oldani told the Economist magazine that they shared a passion for fast cars and says Carlo loved absurd comedy shows such as The Simpsons.

Another pal, Michele del Vecchio, recalled how they rented raunchy comedy videos.

Though both men were impressed by Carlo’s kindness and remember him frowning on pre-marital sex, they say he never discussed religion with them.

His fatal cancer, at first mistaken for flu, came when he seemed to be growing into a sporty, 6ft tall young man.

However, his mother says he accepted his suffering with equanimity and promised her she would have more children again, though she was then 39 and thought she was infertile. Her twins Michael and Francesca were born four years later.

It was at Carlo’s funeral, she says, that she realised she might be burying a future saint.

Scores of strangers came to pay their tributes to him and the priest described acts of kindness she was unaware of.

A few years later members of his Milan church presented his cause to Rome: the first step on the ladder to sainthood. Then in 2019 his remains were exhumed for identification – another key part in the process.

Because of his affinity with St Francis, he was entombed in Assisi and soon their statues will also stand side-by-side in the town.

Mementos of the Blessed Carlo Acutis are sold in shops in Assisi

A person holds a picture of Carlo Acutis, on the day Pope Leo XIV held a general audience in St. Peter’s Square, at the Vatican

The final stage of Catholic canonisation requires the proposed saint to have performed two posthumous miracles.

Carlo was deemed to have done so by saving the lives of two people who seemed certain to die before prayers were offered to his holy relics. The first was four-year-old Brazilian boy Matheus Vianna, who was born with an annular pancreas, a defect that prevented him digesting food.

Expected to die of malnutrition within a year, in 2013 Matheus’s family took him to pray before a piece of cloth cut from Carlo’s clothing, which was being displayed in churches around the world. That night, it is said, Matheus ate a hearty meal of beef and chips which stayed down, and he is now a healthy teenager.

The second purported miracle came in 2020, after Valeria Valverde, aged 21, a Costa Rican studying fashion in Florence, was knocked off her bike and incurred such serious head injuries, she was placed on a life support machine.

Medics gave her no chance but she reportedly made a full recovery after her mother knelt before Carlo’s tomb and begged for his intercession. Both miracles are said to have been verified by independent doctors.

Since then, many others are said to have been cured by praying to Carlo’s relics – strands of his hair, strips of his clothes, and his pericardium (the sac that surround his heart). Already they have been displayed in 24 countries, with Scotland, the Philippines, India and a 32-city tour of Australia on the upcoming itinerary.

Meanwhile, institutions named after him are springing up everywhere. Wolverhampton has its Carlo Acutis parishes and Runcorn in Cheshire and Merthyr Tydfil its Carlo Acutis schools. But in a life spanning just 15 years could he, or anyone, have done enough to warrant a place at the Lord’s side in heaven, as canonisation decrees?

Pilgrims pray and pay their respects at the tomb of Blessed Carlo Acutis in March

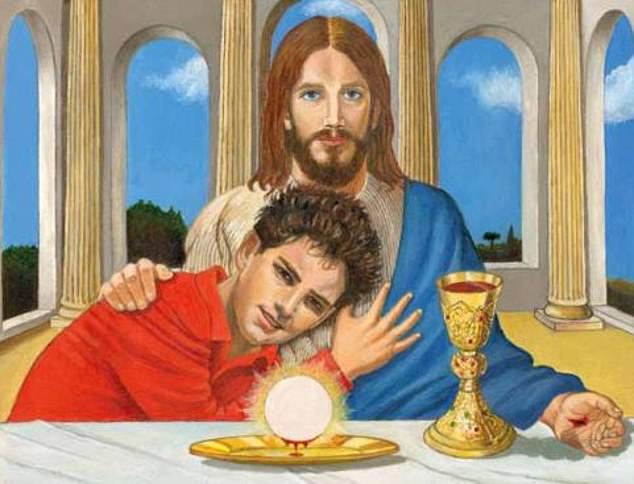

A Portrait shows the 15-year-old Acutis with Jesus Christ

He is not the youngest person to have done so. Italian farmer’s daughter Maria Goretti was 11 when she was stabbed to death while fighting to protect her virginity from a would-be rapist.

Now a patron saint of chastity and forgiveness, she died in 1902 and was canonised 48 years later.

British Monsignor Anthony Figueiredo, who has written a biography of Carlo and guards his relics on their overseas tours, is sure of his saintliness. ‘A lot of people are critical and I think part of that is down to Carlo’s age,’ he concedes. ‘And yes, the church does want to put forward these youthful saints, so that the young follow their example.’

He pauses and gestures towards the crowds beyond the window.

‘But hey, have you seen all those people?’ he says, shaking his head in wonder. ‘That’s all part of this. It has just grown and grown. He has become a phenomenon.’

Indeed, he has, as we shall doubtless see this morning. And perhaps, with so much misery in the world, that is reason enough to celebrate the coming of a saint who appears to have been purpose-made for tomorrow’s generation.