This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

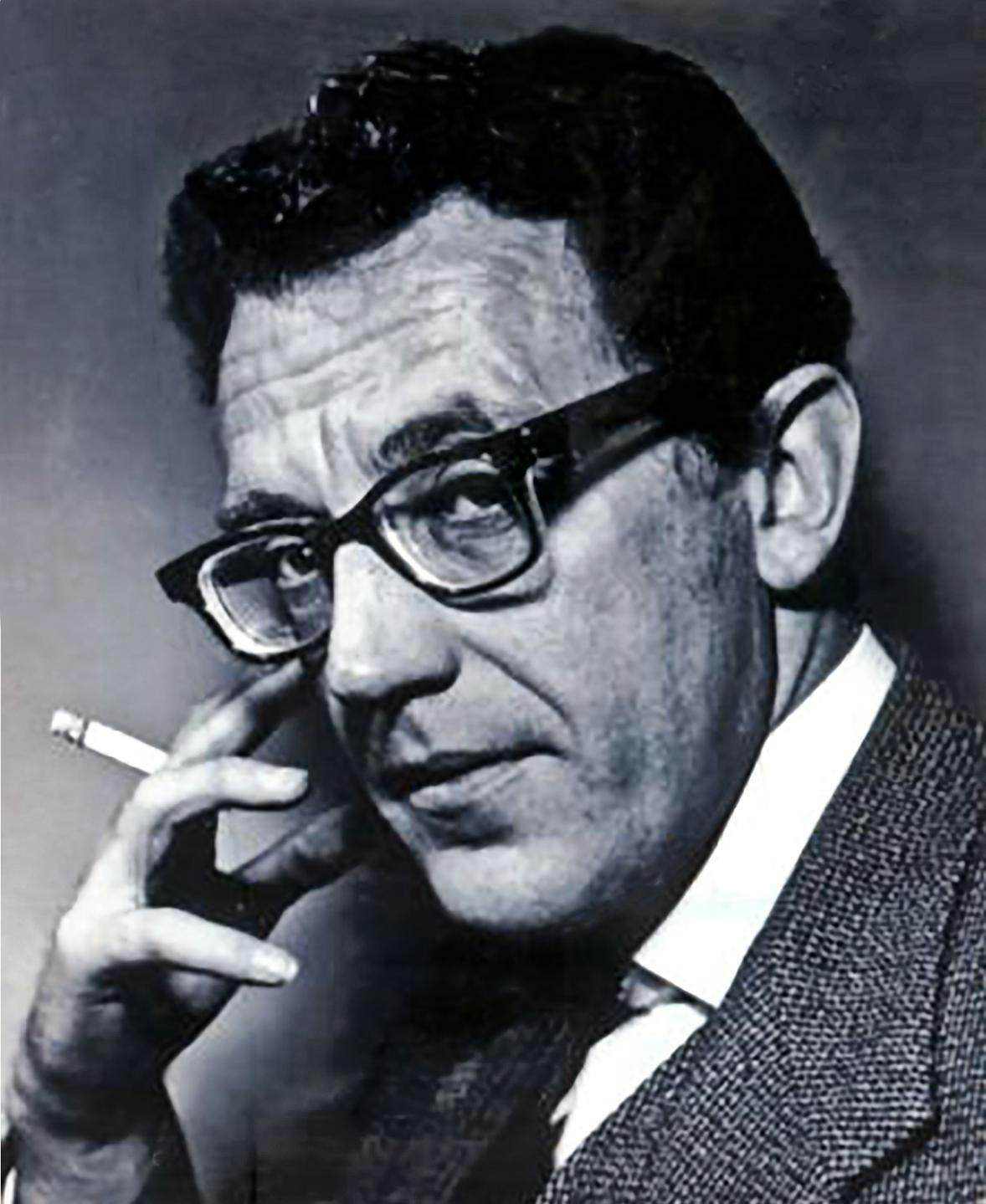

No newspaper columnist gave greater joy to readers in the years 1957–2006 than Michael Wharton. He was a Tory anarchist who detested progress, hated communism, had no love of America or of capitalism, dreamed in a self-mocking way of an ideal feudal past, spoke up for unfashionable minorities (including the Afrikaners, the Serbs and the Ulster Unionists) and had a Dickensian gift for inventing characters who epitomised the absurdities of modern life.

His “Way of the World” column in the Daily Telegraph, which he wrote under the name Peter Simple, was home to Dr Heinz Kiosk, chief psychiatric adviser to the White Fish Authority and many other bodies, whose impending cry, “We are all guilty”, would send people rushing too late for the exit.

Also to be found in the column were: Mrs Dutt-Pauker, Hampstead thinker and Stalinist, who lived at Marxmount, a palatial mansion in north London, but was also chatelaine of Leninmore, in the west of Ireland, acquired during the Cuban missile crisis; J. Bonington Jagworth, leader of the Motorists’ Liberation Front, defender of “the basic right of every motorist to drive as fast as he pleases, how he pleases and over what or whom he pleases”, whose chaplain, the Rev John Goodwheel, known as “the apostle of the motorways”, has a mobile Romanesque cathedral; Julian Birdbath, “last citizen of the Republic of Letters” and discoverer of the missing Brontë sister, Doreen; Lt Gen Sir Frederick (“Tiger”) Nidgett, founder of the Royal Army Tailoring Corps and Hero of Port Said, the man who, as he tells us in his autobiography Up Sticks and Away, “held the fort in the dark days of 1942 when the Nazi hordes were bellowing tastelessly, in true Teutonic fashion, at the gates of Egypt”.

Wharton was born Michael Bernhard Nathan in 1913 in Shipley, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. His father, Paul Sigismund Nathan, was a wool merchant of German-Jewish descent whose parents had emigrated from Magdeburg to Bradford in the 1860s and lived in a large house, speaking German to each other and looking down on Michael’s mother, Bertha, née Wharton, a Yorkshirewoman of humble origin.

She entertained the delusion that her son was the rightful heir to a great house, Wharton Hall, in Westmoreland: the conceit with which he begins his first volume of autobiography, The Missing Will, in which he remarks that he and his parents did not fit in anywhere.

He had an early and invincible love of words, learned them with ease and would later study languages such as Welsh because he delighted in them for their own sake. “His application and ability to learn are excellent,” his first school report said. “But he is too passive and lacks initiative.” The second half of this he often quoted against himself. He went from Bradford Grammar School to read classics at Lincoln College, Oxford, with a scholarship conferred by West Riding County Council, needed because his father’s business was in decline.

Wharton found himself unable to apply his mind to academic work. He instead conducted what he called “an unremitting war on reality”, discovered the pleasures of drinking, consorted with amusing companions, made unprovoked attacks on college furniture and wrote Sheldrake, a novel of 120,000 words about a nightmarish city in the West Riding. In the summer of 1936, he was sent down without a degree, married Joan Atkey, who had been studying at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, and walked round mid-Wales with her.

The book was rejected. This was a terrible blow. He found himself unable to complete another. He and his wife lived as penniless bohemians in London, and in February 1938 their son Nicholas was born. At this point Michael Nathan, as he still was, changed his name to Michael Wharton: “I wanted to escape from the oddity and even absurdity of my early life.”

They left London and rented a cottage for ten shillings a week in the Eden Valley in Westmoreland, a part of England he loved. Wharton found he could earn £12 a time for articles in Punch, and also had a short story published in the first issue of Cyril Connolly’s Horizon.

In 1940, Wharton joined the Royal Artillery. He expected, in his self-denigrating way, to fail as a soldier, but the Army recognised his ability, made him an intelligence officer, and by the end of the war he was a Lieutenant Colonel serving on the staff in India, where as an amorous and attractive man he had love affairs and thought of writing an Anatomy of Boredom, on the lines of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy.

When he rejoined his wife after the war, he found he could not live with her. He went alone to London, had a miserable time, bumped into a pre-war friend, Constantine FitzGibbon, in a pub in Fitzrovia, and through him got work at the BBC, where he was employed in various capacities for the next ten years. He performed his work with enviable ease, but was unable to subscribe to the progressive BBC ethos, found himself described in his file as “not BBC material” and was never put on the staff.

In 1951, he met Kate Derrington, a beautiful young woman who had hitchhiked from Birmingham to meet people at the BBC. They went to bed. She became pregnant and would not have, as he suggested, an abortion. At this point he suffered a crippling bout of depression and “gazed into the void”.

He recovered as soon as he decided to marry Kate, who in due course gave birth to a girl, Jane. The marriage ceremony was performed at Marylebone Town Hall, with Constantine FitzGibbon and his wife Theodora as witnesses. Wharton nevertheless continued, from time to time, to suffer from depression, at times so bad he resorted to electroconvulsive therapy, which seemed to help.

Whilst staying with the FitzGibbons at their house in Hertfordshire, he became friends with Colin Welch, a brilliantly amusing journalist on the Telegraph who recruited many gifted people to that paper. One day Welch told Wharton he was looking for a full-time collaborator for the Peter Simple column. Wharton made no particular response, but Theodora shouted, “Can’t you see, you fathead? He’s offering you a job.”

Wharton agreed to work for Welch: “So, on New Year’s day, 1957, after a sleepless night of confused celebration, I sat down for the first time at my desk in the Daily Telegraph with one of the most appalling hangovers I have ever had in my life, and without a single idea in my head.”

Welch soon went on to higher things, whereupon Wharton managed to jettison such assistants as were thrust upon him, and to write unaided a thousand words a day, four days a week, from 1960 until 1987, when the Telegraph left its grand Fleet Street offices for tawdry premises in Docklands, to which Wharton declined to go. He nevertheless continued the column for one day a week until three days before his death, aged 92, in 2006.

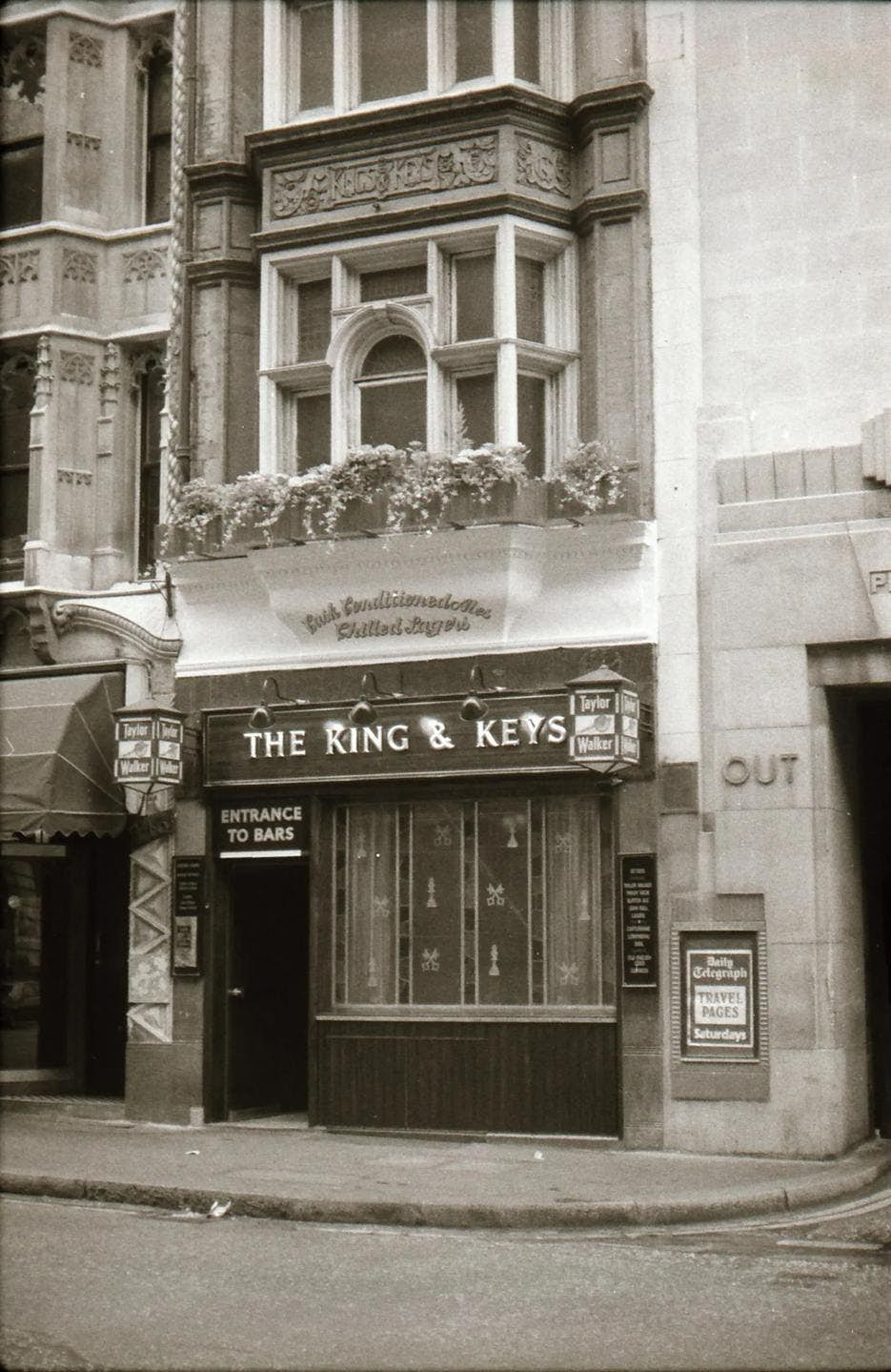

In A Dubious Codicil, the second volume of his autobiography, Wharton draws an immortal picture of life in the King & Keys, the sordid pub next to the Telegraph in Fleet Street. Many of the staff of this great, respectable paper, selling over a million copies a day to its great, respectable readership, behaved like drunken maniacs.

Wharton did not subscribe to the Thatcherite view that the power of the trade unions must be broken. He was a supporter of the print unions, whose Luddite resistance to new technology prolonged the life of the old Fleet Street. Once the printers had been smashed by Rupert Murdoch’s move of The Times and the Sun to Wapping, journalists were made to spend longer hours in the office, drink less and churn out more but duller words.

Welch became, in time, the lover of Kate Wharton, and had two children with her. Michael Wharton moved to Battersea Park Road, where he led a life of unvarying routine, catching each day the same two buses to the Telegraph, and having most of the column written in the margin of that day’s paper by the time he arrived. In 1974, he got married for a third time, to Susan Moller.

When he mentioned in his column a book called The Naked Afternoon Tea, by Henry Miller, a reader wrote in to complain she could not find it in any bookshop. He was recognised as the greatest satirist of his day, pouring into his journalism the genius which he might have poured into books. The pre-war novel was published in shortened form in 1958, but found few admirers.

Wharton insisted he was no hero, and it is true that during the Second World War he did not seek out danger, and by good fortune missed several perilous episodes. But in peacetime he had the courage to defy received opinion for half a century. As Matthew Arnold wrote of Oxford, the column was “home of lost causes, and forsaken beliefs, and unpopular names, and impossible loyalties!”

Wharton was a shy man, and when invited, as sometimes happened on the strength of his column, to meet grand people, would become monosyllabic. He regarded television as an evil device, and on the one occasion he submitted to a broadcast interview, drank heavily beforehand and replied to every question, “Oh, I wouldn’t say that.” His anti-careerism was heroic. He had the courage to mock the modern world and find laughter in despair.

This profile is taken from Gimson’s Heroes: Brief Lives from Boudicca to Churchill, published by Constable.