This article is taken from the April 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

Legend reports that the great and magnificent Emperor Frederick I never died; rather he sleeps under the Kyffhäuser Mountains in Thuringia, waiting for the day when can awake and reignite the greatness of the German Empire. Or so the story goes …

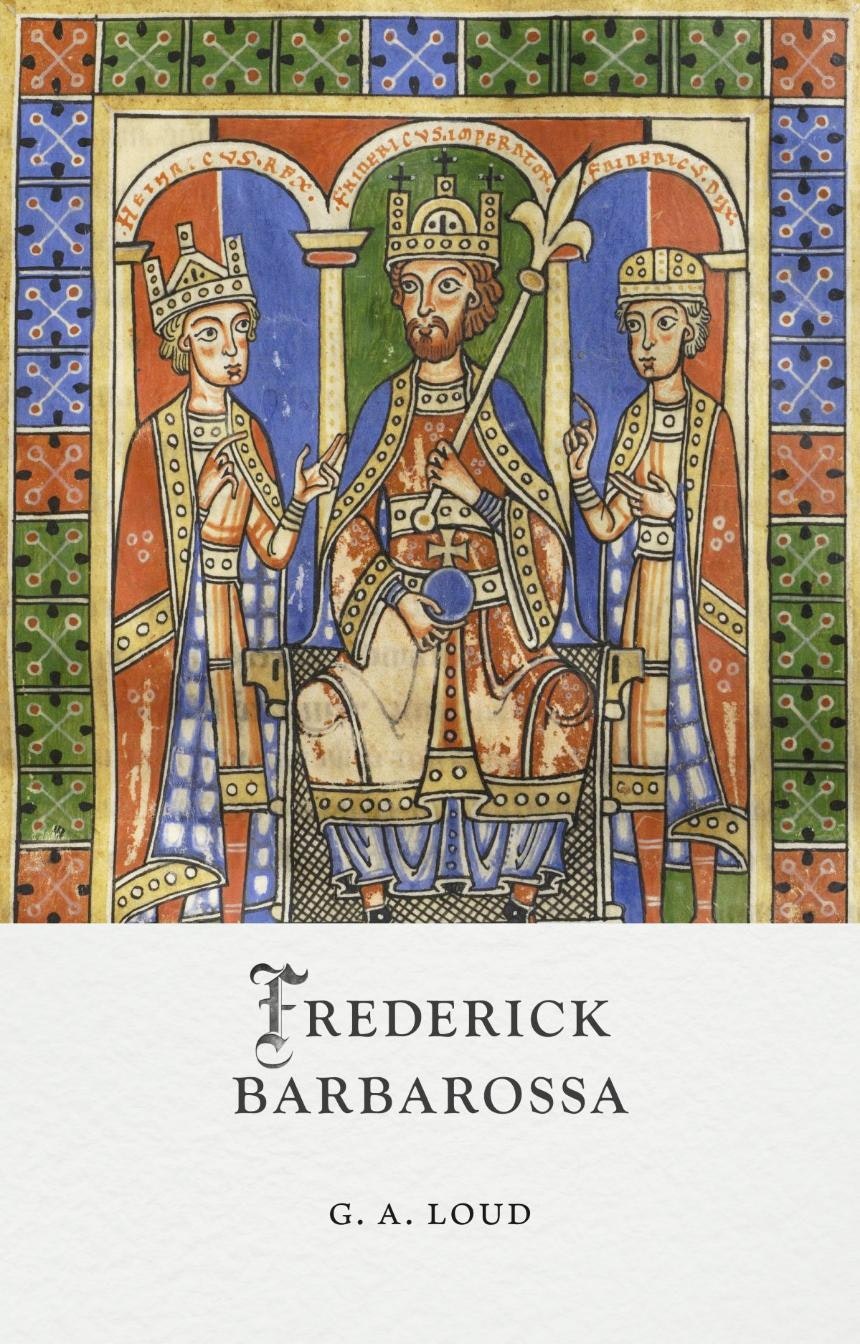

In fact, this legend first emerged in the late thirteenth century with the myth-weavers embroidering it around the later emperor Frederick II, not his grandfather Frederick I (1122-1190). This story is one of the many long-held convictions Graham Loud examines — and often explodes — in Frederick Barbarossa, a new and punchy history of this most famous of German emperors.

Far from adding an extra layer of lustre to the emperor’s heroic credentials, Loud instead offers a rather more complex and nuanced portrait of an all-too-human ruler attempting to manage the enormous challenges confronting him.

Frederick himself became ruler of Germany in the year 1152, when he managed to persuade enough imperial nobles to endorse his elevation to the throne. He then remained in power until his death on crusade almost four decades later in 1190. During his long reign he undertook a wide range of arduous tasks, several of which had been pilling up under his predecessors. Many of these drew his gaze southwards towards Italy where many different claimants sought to erode his authority.

In Lombardy, a defiant cluster of cities increasingly asserted their independence from imperial control. Then, in the Norman territories of southern Italy and Sicily, the reigning dynasty defied the Empire’s control, a matter warranting urgent attention. The Byzantine Empire only compounded matters as it sought to reassert its own claims to the Italian peninsula, whilst the Pope sought to shake off the emperor’s perceived right to intervene in the Church’s affairs (a very old and bitter argument).

Set against this formidable array of troublesome subjects and political rivals, Frederick could call upon substantial armies, the considerable revenues produced by his own lands, the prestige of his imperial office as well as the support of many leading churchmen across his empire. Even so, his position was not nearly as overawing as it might appear.

In addition to his challenges in Italy, he also needed to maintain the peace amongst Germany’s combustible princes and aristocracy, whilst managing the day-to-day business of government — all this with a tiny bureaucracy (remarkably, during the 1170s, he had only one notary to write all his documents).

In this crisp and authoritative biography, Loud serves as a very capable guide to the many international wrestling matches that followed Frederick’s accession to power. Like so many contests between entrenched opponents, the resulting struggles were bloody — both metaphorically and literally — and were generally indecisive in their outcomes.

Despite leading six expeditions into Italy, Frederick’s position in Lombardy grew weaker, not stronger, whilst his persistent wrangling with the Pope frequently ended in embarrassing climb-downs. Moreover, by the time of his death Sicily and Italy remained independent and free from attack (even if his son and successor Henry did gain power soon afterwards).

Frederick’s final venture, a crusade to the Holy Land, managed to cut a brutally efficient path through Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), but ended in disaster with Frederick’s own death when he drowned whilst swimming in the river Saleph.

The Frederick who emerges from this book is so much more interesting and plausible than the superhero of legend. Loud’s biography is neither a hagiography nor a hatchet job; instead he presents Frederick as someone with the inclination, and to some extent the resources, to attempt to bend major political forces and processes to his will.

In many cases he proved a pugilistic if not especially successful protagonist, but in working through the events of his life we gain a substantially better grasp of the pressures shaping the medieval world as well as the powers and limitations surrounding rulers in their attempts to impose dominion over tens of thousands of square miles of territory. If nothing else, Frederick’s determination and tenacity, as well as the lasting impact of his actions, warrant his place in the history books.

In short, this is good-quality history: history written by a leading expert without any deference towards legend, wishful thinking or modern agendas, but rather offered with a clear desire to understand a complex and fascinating individual in his own very human context.