As Labour limps to the end of its first year in office, the marks are in and the verdict is brutal.

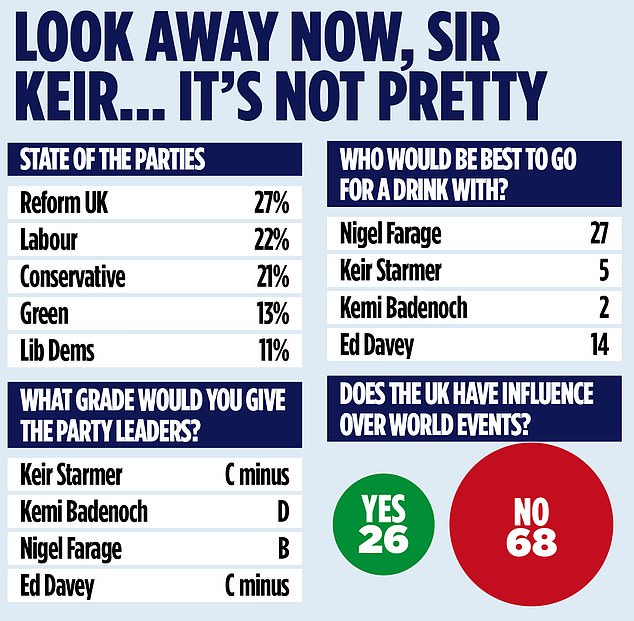

My latest poll finds that based on what they have seen so far, nearly four in ten voters would give Keir Starmer an F for ‘fail’. Among the rest, the average grade is a C minus. Even Labour voters can only bring themselves to award a C plus.

It’s not just that many disapprove of the Government’s agenda. Half the electorate, including nearly as many 2024 Labour voters, say they don’t understand what it is. This is hardly surprising, given the start they made.

We can imagine Keir Starmer’s first meeting with his senior officials a year ago this week.

‘Congratulations, Prime Minister,’ opens Sir Humphrey. ‘Might we discuss your early priorities for government? I assume you’ll want to focus on economic growth and improving public services.’

‘All in good time,’ says Starmer. ‘First, cut the winter fuel allowance. Then find a way to make it more expensive to employ people. Oh, and make farmers pay inheritance tax.’

‘I see,’ Sir Humphrey replies hesitantly, casting a nervous glance at a puzzled colleague. ‘Anything else, Prime Minister?’

‘Yes. Give the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. And rent them back.’

My latest poll finds that based on what they have seen so far, nearly four in ten voters would give Keir Starmer (above) an F for ‘fail’

It’s not just that many disapprove of the Government’s agenda. Half the electorate, including nearly as many 2024 Labour voters, say they don’t understand what it is

If the scene seems fanciful, it’s probably because it exaggerates the sense of purpose with which Labour assumed power.

A series of U-turns – a feature of Starmer’s administration since the early days but now so abundant it’s hard to keep up with them – has only added to the sense of incoherence and confusion.

Broken promises to the ‘Waspi women’; Sue Gray’s brief tenure as No 10 chief of staff; reversals on winter fuel, the grooming gangs inquiry, and whether excessive immigration is or is not turning Britain into an ‘island of strangers’ – these combine to show a Government with little sense of direction.

Starmer’s colossal turnaround on welfare reform compounds the damage, for three crucial reasons – both political and practical.

First, even at its most moderate, the Labour Party has never fully shaken voters’ suspicions that it is too soft on welfare and can’t be trusted with taxpayers’ money. The backbench rebellion and the Government’s retreat in the face of it show these doubts to be well founded.

Second, Starmer’s climbdowns will cost real money: some £4.5 billion, according to ministers’ own figures. That means (even) higher taxes or (even) more borrowing, or probably both, at a time when Britain needs neither. It also makes it harder to hit the new Nato target of spending 5 per cent of GDP on defence within ten years – a policy which most voters support, as does (so he currently says) the Prime Minister.

As Labour limps to the end of its first year in office, the marks are in and the verdict is brutal, writes Lord Ashcroft (above)

Sue Gray’s (above) brief tenure as No 10 chief of staff, reversals on winter fuel and the grooming gangs inquiry are just some examples which combine to show a Government with little sense of direction

Third, while an occasional pivot can show a government that listens and learns, a succession of them erodes confidence and credibility.

‘We need somebody strong at the head of our country to go head-to-head with Trump, but he can’t even keep control of his own party,’ as a woman put it in one of my recent focus groups.

‘What’s he going to do on other policies?’ asked another. ‘When he makes hard decisions and gets challenged, he just seems to flip.’ In a dangerous world, people want a leader they can rely on.

Despite all this, a fair but dwindling chunk of voters still gives Labour the benefit of the doubt. They argue that 12 months isn’t long to correct the mistakes of 14 years. But listening to those who turned out for the party, it’s clear that many are struggling to look on the bright side.

Few see any tangible signs that Starmer’s team has started to turn things around.

As one of the party’s previous backers told us, ‘There’s no noticeable change that says, “Labour’s in, this has happened”.’

A fair but dwindling chunk of voters still gives Labour the benefit of the doubt – they argue that 12 months isn’t long to correct the mistakes of 14 years

Few pollsters see any tangible signs that Starmer (pictured) and his team has started to turn things around

If the Government lacks a sense of purpose, many feel the same is just as true for the Conservatives. More are starting to notice Kemi Badenoch and to like what they see. But the party has yet to break through and her overall grade from voters was a D.

They recognise her conundrum: how to be visible and relevant without claiming to have all the answers so soon after being booted out of office.

One answer is to show a proper understanding of what they got wrong and what is needed to put it right.

Another is to rediscover what one former voter called their ‘North Star’, the guiding principles that animated and united the Tories when they were at their best.

Nigel Farage tops the grade table for the year – the only leader to get an A from his own voters, and a B overall. He has picked up the extra marks by being visible, getting people talking, articulating people’s frustration and turning it into local election votes.

People see that his party is branching out beyond immigration to talk about energy, industry, welfare, policing and more.

Voters are starting to notice Kemi Badenoch (above) and to like what they see – but the party has yet to break through and her overall grade from voters was a D

Nigel Farage (above) tops the grade table for the year – the only leader to get an A from his own voters, and a B overall

But Reform-curious voters wonder about the practicality of some of their ideas – such as reopening Welsh coal mines, or charging non-doms a £250,000 fee in lieu of tax and sharing the proceeds among low-paid workers – and note the party’s expensive plan to drop the two-child benefit cap.

Some acknowledge Farage’s need to win over voters from all sides, but many will want something firmer when choosing the next government. ‘Be a bit more grown-up, tone it down. You’ve got my attention now. Win me over,’ one potential supporter said.

Attention brings scrutiny. This year was just the mocks. As the final exams approach, the questions will get harder.