New Year’s Eve at the end of 2029, six months after the formation of Britain’s ‘Rainbow Coalition’ government, brought the first real trouble. A strike by power supply workers plunged the country into darkness during the Big Ben countdown to Auld Lang Syne.

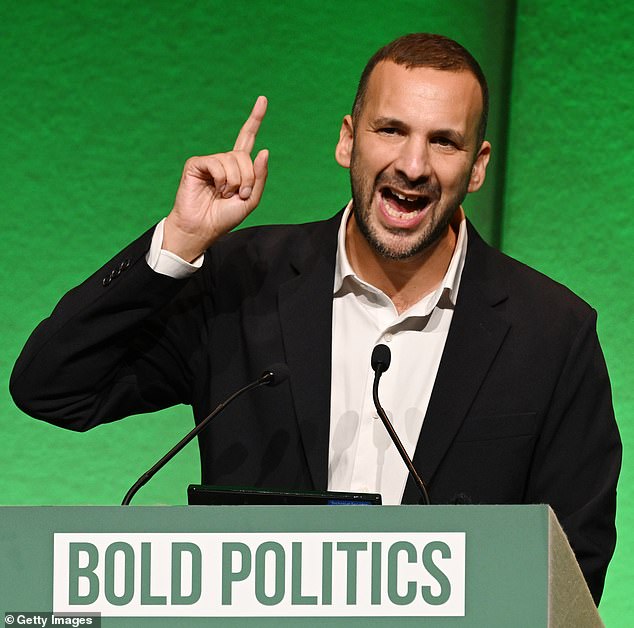

In preceding weeks the new Energy Secretary, Zack Polanski, had tried to play tough with trade unions, boasting that there was ‘easily enough wind power to keep the lights on’. Mr Polanski was proved wrong at precisely nine seconds to midnight.

TV screens showing the festivities from London suddenly went blank. A rainbow-illuminated London Eye disappeared into pitch blackness. Similar scenes played out in cities across England, Scotland and Wales.

With the London Underground paralysed, hundreds of thousands of revellers in the capital were stranded.

There was looting in Liverpool. Hooligans set fire to a homeless shelter in Wrexham, causing several deaths. Race riots erupted in Birmingham. Scores of prisoners simply walked out of a prison in Glasgow after its state-of-the-art electric security went phut. Not for the first time in his career, Justice Secretary David Lammy faced questions in the House.

The power cut, first of many, turned Britain into an international joke.

A strike by power supply workers plunged the country into darkness during the Big Ben countdown to Auld Lang Syne on New Year’s Eve at the end of 2029

In preceding weeks the new Energy Secretary, Zack Polanski, had tried to play tough with trade unions, boasting that there was ‘easily enough wind power to keep the lights on’

Union leaders, who were being quietly encouraged by their ally Angela Rayner, the new Home Secretary, called a three-day week in several industrial and service sectors. NHS waiting lists lengthened.

With bin collections stopped, enormous rats became commonplace, with consequent outbreaks of listeria, Weil’s disease and toxoplasmosis.

Arson attacks increased, teenage fire-raisers being gleefully aware that the Fire Brigades Union was at the vanguard of the public sector strikes. Jobcentres and government offices were picketed.

The only educational establishments to stay open were the few private schools that had survived Bridget Phillipson’s class warfare back when Lord Starmer was in Downing Street. With the government now threatening to abolish independent education altogether, they wouldn’t last long.

The new Prime Minister, Ed Miliband, had no option but to ration electricity for homes so that precious supplies could be used for hospitals, police stations, military bases and the dealing rooms in the Square Mile.

The City was arguably the last part of the country that was still world-class, although top banks and stockbroking firms were losing thousands of analysts to emigration.

Mr Miliband’s pleas for TUC ‘solidarity’ were ignored. The unions wanted Ms Rayner in No 10 and they were in no mood for compromises. They had fallen out with Mr Miliband over his ideological devotion to Net Zero.

The chaos caused by the blackouts was worse than anything experienced in the early 1970s. With cash now so out of fashion, electricity was crucial for shop payments. Long queues formed outside supermarkets and it was estimated that a weekly shop now took five hours instead of the old 45 minutes.

Electricity was also essential for lifts in high-rise flats, for retail premises doorways, for large parts of the rail network and, of course, for computers. Millennials and Gen-Z youngsters, weaned on wifi, became disorientated and panicky. Even if they were able to charge their mobiles, they often had no signal to connect them to the internet. NHS doctors reported a rise in mental-health cases.

The economic damage was as bad as that of the Covid lockdown. Mr Miliband and his Chancellor, Torsten Bell, flew to the International Monetary Fund for a bailout plan, but it looked as if further aid would have to be sought.

The European Union shrugged and said: ‘There is no money’. In Washington DC, President Vance had still not forgiven the British Left for its efforts to help the Democrats win the recent US election.

Foreign Secretary Dame Emily Thornberry did not deny that she was might apply to join China’s notorious Belt and Road initiative under which Beijing exchanged aid for access to a stricken country’s natural resources.

The Chinese, short of liquefied natural gas since the toppling of Venezuela’s Maduro regime in 2026, were interested in Britain’s rich deposits of shale gas, which eco-sensitive Westminster had obstinately refused to use.

Britain’s election in the summer of 2029 had seen, basically, a seven-way draw. With the Conservatives and Reform splitting the Right-wing vote, the inevitable happened: a Left-wing alliance of Labour, Greens and Lib Dems went into coalition talks with nationalist parties from Scotland and Wales.

After four days and nights of haggling, the SNP and Plaid Cymru agreed to enter UK government for the first time. Their price was independence referenda in Scotland and Wales, to be held in the summer of 2030.

Reform had taken scores of seats from all the main parties but that was not enough to win power. A big enough part of the centre-Right vote stayed with the Tories, who held on to many of their southern English seats and even took back a few from the lacklustre Lib Dems. Labour suffered terrible losses on election night.

And yet, thanks to a repetition of the informal election pact that helped Labour to its landslide victory in 2024, the Left again ‘came through the middle’ of the competing Tories and Reform.

The prideful refusal of Nigel Farage and Kemi Badenoch to agree a pre-election non-aggression deal meant that although 52 per cent of electors voted for them, the two Right-wing parties fell agonisingly short of the parliamentary seats needed to form a government, even with Ulster’s Unionists.

The Treasury’s first task, even before the new Chancellor’s appointment was confirmed, was to halt a run on the pound. The Bank of England persuaded the markets that no new government could print money willy-nilly, and for a while that saved the day.

But fresh doubts were growing, particularly with the Left increasingly flexing its muscles in parliament. Airlines started imposing surcharges and the price of a family package holiday doubled.

Green Party backbenchers, whipped up by their publicity-addicted leader, were agitating for domestic rental properties to be nationalised. Their proposed property laws were based on those of communist Cuba, ‘but without the loopholes’.

The Greens had already succeeded in lobbying for a national speed limit of 50mph on motorways, as happened in the oil crisis of 1973. All petrol and diesel cars would now have to be scrapped by 2035. Agas and wood-burning stoves would become illegal before the end of the parliament. Councils were forbidden from flying national flags.

The Commons supported a Private Member’s Bill scrapping all time limits for abortions. Further such Bills demanded an end to lawn mowers – bad for the climate, it was argued – and sweeping restrictions on the keeping of pets, which was held to be ‘animal slavery’. Guide dogs would be exempted but police sniffer dogs would not.

The new Prime Minister, Ed Miliband, had no option but to ration electricity for homes so that precious supplies could be used for hospitals, police stations and military bases

The only light on the horizon was Home Secretary Angela Rayner’s fondness for the King. The two of them had become tremendous friends

Negotiations to rejoin the EU were being led by the Deputy Prime Minister, the irretrievably lightweight Sir Ed Davey, but they soon hit a snag

The RSPCA had been given an office inside the Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs, and farmers predicted that a White Paper on the meat industry would double the cost of fresh meat.

Public spaces such as London’s Hyde Park and Manchester’s Heaton Park had been allowed to ‘rewild’ and were already becoming over-run by brambles and ragwort.

The Lib Dems were clamouring for electoral reform (which would ensure that coalition government became a perpetual fact of life). Not to be outflanked by the Greens, Lib Dem policy advisers were also looking at making vegetarian food compulsory in all government kitchens. It could mean that from school dining rooms to Naafi canteens and even Windsor Castle banquets, no meat could be served.

A majority of the government’s backbenchers favoured abolition of the monarchy and it was not known how long Mr Miliband would be able to keep them at bay.

The only light on that particular horizon was Home Secretary Rayner’s fondness for the King. The two of them had become tremendous friends and Ms Rayner was delighted, with much suggestive winking, to be appointed to the Order of the Garter. His Majesty, meanwhile, had thought it politic to turn the gardens of Buckingham Palace into a skateboard park for inner-city kids. One wing of the palace was converted into offices for the expanding Civil Service.

Labour backbenchers competed for attention with their coalition partners. They demanded ‘luxury’ taxes on four-wheel-drive cars, sparkling wine, jewellery (including wristwatches) and books. GB News was forced off the airwaves by a browbeaten regulator. The Free Speech Union was proscribed.

Foreign policy lurched leftwards, Dame Emily distancing herself from Britain’s transatlantic alliance. The Foreign Secretary initially gained high approval ratings for this stance thanks to former President Trump’s obnoxious trashing of British military fatalities in Afghanistan. Israel was ‘put on notice’ that London was no longer an admirer and that the Miliband government ‘had the back of the Palestinian people’.

The police, scenting the political breeze on this matter, no longer made even a pretence of investigating anti-Semitic incidents.

Continuation of our nuclear deterrence was in doubt both on cost grounds and because the new government contained life-long CND members. Dame Emily indicated that Britain could support China’s acceptance into the trans-Pacific CPTPP trade partnership. Dame Emily also volunteered to vacate our seat on the UN security council, describing it as ‘a hangover of colonial days’. Not that the UN counted for much these days. Negotiations to rejoin the EU were being led by the Deputy Prime Minister, the irretrievably lightweight Sir Ed Davey, but they soon hit a snag. The main players in the EU were now markedly more Right-wing than the British government and France’s youthful President Bardella, of the National Rally party, did not want ‘more mouths to feed’.

The heady days of 2019, when it looked as if Boris Johnson could use the freedoms of Brexit to make Britain a low-tax, small-state Singapore-on-Thames seemed from a different age.

Chancellor Bell’s first Budget raised tax rates on ‘the rich’ (anyone on a salary of more than £58,000 a year) to 60 per cent, rising to 75 per cent for those on six-figure salaries. It wasn’t just billionaires who were now emigrating to Dubai and other low-tax states. Doctors and dentists were, too.

With corporate taxes also rising, businesses folded like deckchairs. Few village pubs remained. Unemployment rocketed to more than five million. The Budget only just passed through Parliament after a rebellion by Left-wing SNP, Plaid Cymru and Green backbenchers against tentative benefits cuts.

Government borrowing was rising fast. Defence spending was going to be slashed and the Green-led Foreign Affairs Select Committee published a report calling for the Falkland Islands to be sold to Buenos Aires. Argentina’s economy was growing fast under the second term of President Milei and the committee’s chairman said: ‘We should sting the Argies for a hefty price.’

At which point, ladies and gentlemen, the picture fizzles and fades and we return to the current day.

Blessedly none of the above has happened. But it could. Our politics is in a state of pluralist confusion. Reform and the Conservatives are knocking bells out of each other and the main beneficiary is the Left.

Sir Keir won a landslide majority in 2024 on the basis of less than 34 per cent of the vote. He managed that largely because Reform and the Tories took votes from one another. For any Right-winger who did not belong to one of those two parties it was maddening, and financially ruinous. For actual members of Reform and the Conservatives it was suicidal.

As things stand, something like the nightmare scenario described above could well happen.

Some voters might think: ‘Well, the last coalition led by David Cameron and Nick Clegg turned out to be pretty stable.’ But that government had only had two partners and its two main protagonists broadly saw eye to eye.

A coalition of three, four or five Left-wing parties would likely prove much more rackety. What would happen if, say, the Greens’ leader, the media-savvy Comrade Polanski, kept topping other coalition party leaders in the opinion polls? Would he be able not to crow about it?

If Scots Nats and Plaid Cymru were part of a UK government it would surely be in their interest to make the regime unstable, as that would assist their chances of gaining independence.

You only have to look at the fragility of Israel’s multi-party coalitions to see how small parties in a government can bring the entire edifice tumbling to the ground. And that is before you factor in the economic and societal destruction that a hard-Left regime would do to our country. It would make the Starmer government look a model of wisdom.

We need a government that spends less on benefits and more on defence, a government that lowers taxes and makes the most of Brexit, a government that restores aspiration and initiative to the individual and, please God, scraps Net Zero. The Conservatives and Reform agree on such policies. Together they could introduce them and save our country. At loggerheads, they cannot.

Big Ben is ticking. Let’s not wait until New Year’s 2029 before the Right unites.